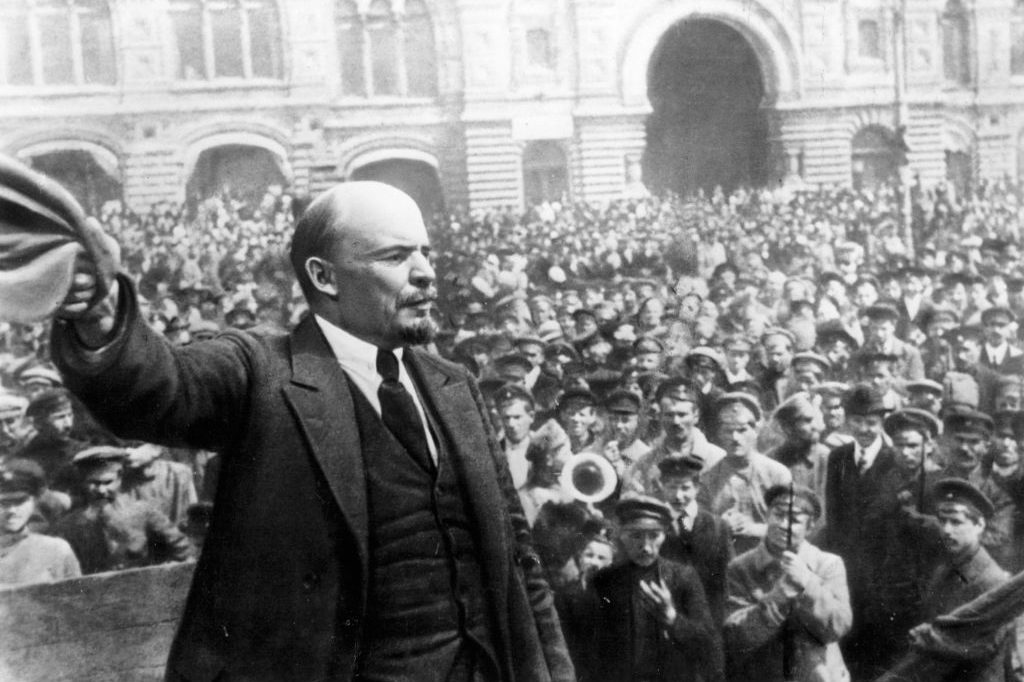

The year 2024 marks the centenary of Vladimir Lenin’s death. In April of that year, the consummate communist, having blighted as many lives as he could, finally shuffled off his mortal coil, aged fifty-three.“That was young,” you may say. But I reply, “Not nearly young enough.”

As we embark on what is sure to be an eventful year, it is worth pausing to remember the hideous legacy of that ice-cold totalitarian. What I have in mind is not so much Lenin’s butcher’s bill as his more general modus operandi. Estimates of the number of people Lenin had tortured, maimed and murdered vary, but are always well into the millions. But what is somehow even creepier is his model of government.

I was reminded of this in November when Miguel Cardona, Joe Biden’s secretary of education, gave a talk to explain “education department priorities.” Talking up a kinder, friendlier department, he said, “I think it was President Reagan [who] said, ‘We’re from the government and we’re here to help.’”

I think that was intended to be reassuring. What Reagan actually said, however, as was pointed out about 10,000 times, was the opposite. “The nine most terrifying words in the English language,” the Gipper said, “are: ‘I’m from the government, and I’m here to help.’”

Lenin would have known exactly what Reagan meant — that’s what he liked about government. And if Maximilien Robespierre was a piker by comparison, he had the idea, doing his best to disfigure France in the brief time allotted. An ardent student of that supreme political narcissist Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Robespierre was always going on about “virtue,” though he conflated the emotion of virtue with what a Marxist might call “really existing” virtue. Above all, Robespierre knew achieving the utopia of his dreams would not be easy or painless, which is why he spoke frankly about “virtue and its emanation, terror.”

Karl Marx made a note of that emanation, and in due course his student Lenin aced the class. As he observed in 1906, the dictatorship of the proletariat depended upon “authority untrammeled by any laws, absolutely unrestricted by any rules whatever and based directly on violence.” Thus it is, as Leszek Kołakowski noted in Main Currents of Marxism, that for Lenin “true” democracy requires the “abolition of all institutions that have hitherto been regarded as democratic.” Freedom of the press, for example, Lenin dismissed as “so-called” freedom of the press, a bourgeois deceit.

Lenin said he wanted to vest power in the people. But he insisted that the people had no business in deciding what its interests actually were. (Again, students of Rousseau will hear echoes of his proto-totalitarian idea of the “general will,” which he applauded, and the tawdry particular wills of individuals, which he was always ready to subjugate.)

At the center of the totalitarian impulse is the belief that ultimately freedom belongs only to the state, that the individual should not be treated as a free actor but rather, as Lenin put it, “‘a cog and a screw’ of one single great Social-Democratic mechanism.” Of course, few canny bureaucrats quote Lenin today, his association with tyranny having knocked him out of the great game of political PR.

But is he completely gone? One of the most depressing of recent spectacles has been the rehabilitation of people and movements that, just a few years back, seemed safely consigned to Dr. Caligari’s cabinet of repellent monsters. But watching Eloi-like college students praising Hamas, chanting genocidal formulae such as “From the river to the sea,” even excusing the incontinent maunderings of Osama bin Laden, makes me wonder whether any enormity is sufficiently grave to overcome the moral anesthesia of the entitled class. Someone once described the on-again-off-again socialist Philip Rahv as a “born-again Leninist” — their number, it turns out, is legion.

Which is why I predict an effort, perhaps sotto voce to start, to rehabilitate Lenin. After all, he articulated exactly the desire of everyone, from Klaus Schwab on down, who tells you that he’s from the government and he’s here to help. “What socialism implies above all,” said Lenin, “is keeping account of everything.” Could the Covid police, the bureaucrats pushing a cashless society to gain complete control over your spending and the climate-change fanatics who want to limit your travel and impound your thermostat have put it any better?

Keeping track of your healthcare, disposing of your money, regulating your food and drink and ration of tobacco: there they all are, ready, able and willing to run your life. Just sign on the dotted line and those repurposed nannies will take care of… everything. Note the ambiguous signification of the phrase “take care of.”

What we have seen in recent years is the hideous marriage of political correctness and bureaucratic triumphalism. Its offspring are the chimerical multitude of soft tyrannies we see all about us today — along with an enervation of spirit that renders the public ever less able to respond to the casual indignities that have become such a prominent part of daily life.

Reviewing the early years of the Bolshevik Revolution, Kołakowski noted the almost “superhuman energy” through which the party was able to exact enormous sacrifices from the workers and peasants. It “saved Soviet power” but did so “at the cost of economic ruin, immense human suffering, the loss of millions of lives and the barbarization of society.” We’re not there yet, quite, but we are teetering on the threshold, which is why it is an opportune moment to remember Vladimir Lenin and reject utterly his monstrous legacy.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s January 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply