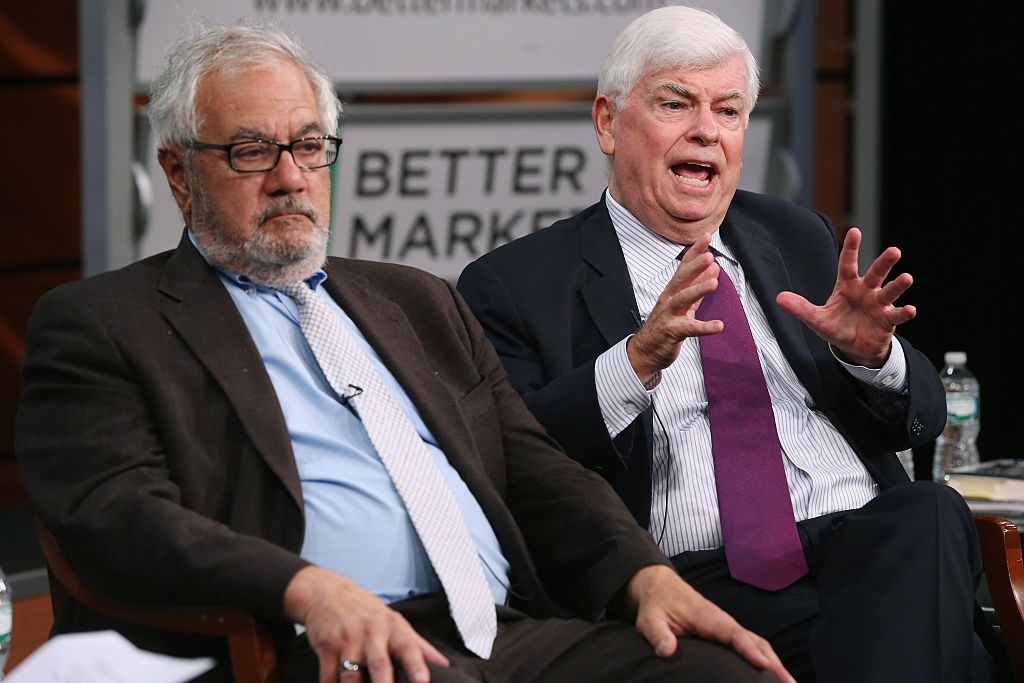

The Dodd-Frank law, enacted in 2010 following the financial crisis of 2007-08, was named for two of its chief architects, Senator Chris Dodd, Democrat of Connecticut, and Representative Barney Frank, Democrat of Massachusetts.

It’s ironic that both had been involved, politically or personally, in exactly what had caused the financial crisis in the first place.

In the 1930s, only about 10 percent of American non-farm families owned their own homes. But that began to change with the New Deal. The Federal Housing Administration was established in 1934 to guarantee mortgages, making banks much more willing to initiate them. (It should be noted that it was the FHA that began the practice of “redlining,” indicating neighborhoods — invariably poor ones with large minority populations — where it would not guarantee loans.)

In 1938, the Roosevelt administration created the Federal National Mortgage Association to help increase liquidity in the mortgage market. Soon nicknamed Fannie Mae, it purchased mortgages from initiating banks and either held them in its own portfolio or packaged them as mortgage-backed securities and sold them to investors. This allowed banks to make many more mortgages than they otherwise could.

But as great ideas often do in countries with democratic politics, Fannie Mae and its clone, Freddie Mac, established in 1970, were allowed to go too far. In 1968, Lyndon Johnson, trying to make the federal balance sheet look better than it was, took Fannie Mae off the federal books, reducing the national debt by billions with the stroke of a pen. Established as “government sponsored enterprises,” Fannie and Freddie were theoretically independent corporations, their stock traded on Wall Street.

But they didn’t have to adhere to many of the rules that other financial companies had to follow, such as capital requirements. They could have up to 40 percent of their capital in mortgages, not 10 percent like commercial banks. They even had their very own regulators, the Office of Federal Housing Enterprise Oversight, or OFHEO for short. And while they were explicitly not guaranteed by the federal government, it was widely assumed that the government would back them up if necessary, allowing them to borrow at below market rates.

By the end of the 20th century, Fannie and Freddie were huge. Combined, they had assets and liabilities larger than the GDP of any country in the world except the United States. And they were headquartered in Washington, DC. In other words, they were thoroughly political.

They made regular campaign contributions to members of Congress with oversight responsibilities. And Democratic politicians temporarily out of office often found remunerative jobs there. Jamie Gorelick, deputy attorney general in the Clinton administration, who had no banking experience, served as the vice chairman of Fannie Mae from 1997 until 2003. During that time she received $25.6 million in salary and bonuses (many of the bonuses were triggered, it turned out, by improper accounting that inflated reported profits).

Because Fannie and Freddie could borrow at cheaper rates, banks could not compete in the lucrative business of bundling mortgages into mortgage-backed securities and selling them to the public. But Fannie and Freddie could not buy many mortgages, such as so-called sub-prime mortgages, or mortgages that were over a certain size, called jumbo mortgages. Banks then began to move into these areas.

Countrywide Financial was one of the largest players in this market. Its TV commercials (“Countrywide is on your side!”) ran constantly. And like Fannie and Freddie, it made sure to be in the good graces of Washington politicians. The company quietly ran a program called “Friends of Angelo,” after the company’s founder, Angelo Mozilo. Through it, mortgages well below market rates were available to favored politicians. Among those who benefitted from this corrupt program was Chris Dodd.

Connecticut’s largest newspaper, the Hartford Courant, criticized Dodd severely when the news became public, and just as he was shepherding the Dodd-Frank bill through Congress, he announced he would not run for another term in the Senate in 2010.

While Barney Frank was not involved in any such insider profiteering, as chairman of the House Financial Services Committee from 2007 to 2011, he had often opposed tightening controls on Fannie and Freddie in order to promote ever-wider home ownership. But with ownership nearing 70 percent, the pool of good credit risks for mortgages was declining rapidly. As late as 2007, Barney Frank wanted to “roll the dice” with Fannie and Freddie in order to ramp up lending in home mortgages.

Ever more creative mortgages were required to push the percentage of home ownership upwards. Soon there were adjustable rate mortgages, teaser-rate mortgages that reset upwards after a period, mortgages with no down payments, with no repayment of principal (so-called balloon mortgages), even mortgages with no questions asked regarding ability to repay. Mortgages had been at 46 percent of GDP in the 1990s. By 2008 they were at 73 percent, totaling $10.5 trillion.

But that, of course, was driving the financial system towards the cliff, as the Wall Street Journal had been pointing out in a series of editorials. When home values declined in 2007, people with little or no equity in their houses began to walk away from their mortgages. This caused the value of mortgage-backed securities to falter and then freeze up. With much bank capital tied up in such assets, the system staggered. Fannie and Freddie, with four times as much of their capital in such securities as other financial institutions, collapsed and had to be taken over by the government. The Great Recession was on.

Two things that will never be in short supply in countries with democratic politics, alas, are the venality Chris Dodd, and the good intentions untethered from reality of Barney Frank. Something to bear in mind as the banking system stumbles once again.