Like millions of other Americans I was riveted by the images of chaos and despair at the Kabul airport as US forces finally left Afghanistan, yet another sad result of a forever foreign policy driven by ignorance, overreach and hubris. But as distressed as I was by the sight of desperate Afghans clinging to the exterior of a moving US Air Force cargo jet, what truly horrified me was the flood of belligerent anti-withdrawal nonsense uttered in print and on TV by an American political and media establishment that has apparently learned nothing since the Korean War, when Gen. Douglas MacArthur provoked China’s invasion of North Korea by pushing too close to the Chinese border.

On and on, network news, cable talk shows and the editorial and op-ed pages of major newspapers trotted out the discredited villains and useful idiots — all of them fluent in Cold War dogma, humanitarian intervention and the ‘War on Terror’ — who in recent years have done so much harm in the world and contributed to the deaths of so many innocent people.

We were, it is true, spared the bombast of former defense secretary Donald Rumsfeld, who mercifully passed away before the Taliban returned to power. But we did hear repeatedly from his doppelgänger, Paul Wolfowitz, intellectual architect of the 2003 Iraq invasion, in the Wall Street Journal. Wolfowitz had wisely kept a low profile since the glorious reformation of Iraq turned sour and had left government, but you can’t keep an American exceptionalist down, especially not one as profoundly vain as the former deputy secretary of defense.

The day after suicide bombers killed 13 US soldiers and at least 170 civilians in Kabul, Wolfowitz was hard at work trying to rejuvenate the ‘Forever War’ against terrorists, who like communists, it seems, just love to congregate in America-hating countries: ‘The war with that gang and its affiliates won’t end because the US has quit… It’s a shame they [Isis-K and the Taliban] can’t both lose…but whoever wins will make Afghanistan a haven for anti-American terrorists.’ That’s why we were in Afghanistan for 20 years and spent more than $2 trillion…to prevent a murderous gang from regaining control of Afghanistan, where they…enabled an attack that killed nearly 3,000 people on American soil.’

This from a man who encouraged the belief that the anti-Islamist Saddam Hussein was in league with the Saudi Islamist Osama bin Laden, and that Iraq possessed atomic bombs and a big arsenal of chemical weapons. Wolfowitz also appears unaware that no Afghan tutored the 9/11 hijackers in avionics, and that no member of the Taliban enrolled in the Florida flight school that taught two Arabs how to pilot the commercial jets that hit the World Trade Center.

But the neo-conservative fanatic of yesteryear was only one in a parade of critics from all across the political spectrum. On liberal National Public Radio came steady lamentations over the abandonment of Afghan women, who had been encouraged by the American occupiers to develop big ideas about their social status, and even to become jet airplane pilots. Wolfowitz expressed solidarity, employing a metaphor that might have been lifted from the movie Being There: ‘Like a gardener who pulls up weeds to allow plants to grow, keeping the Taliban off the backs of the Afghan people would have enabled them to continue some of their impressive successes, particularly in educating girls and women…’

We all agree that Afghan women should be given a fair shake. But did anyone seriously think that prolonging the US occupation would do anything other than prop up the Potemkin village known as the Afghan government and provoke more violence by the Taliban and recruitment to their cause? Yes, many serious people thought just that, like the normally thoughtful columnist Bret Stephens, who in the New York Times posited, ‘I thought we could have maintained a small and secure garrison that would have provided the Afghans with the air power, surveillance and logistics they needed to keep the Taliban from sweeping the country.’

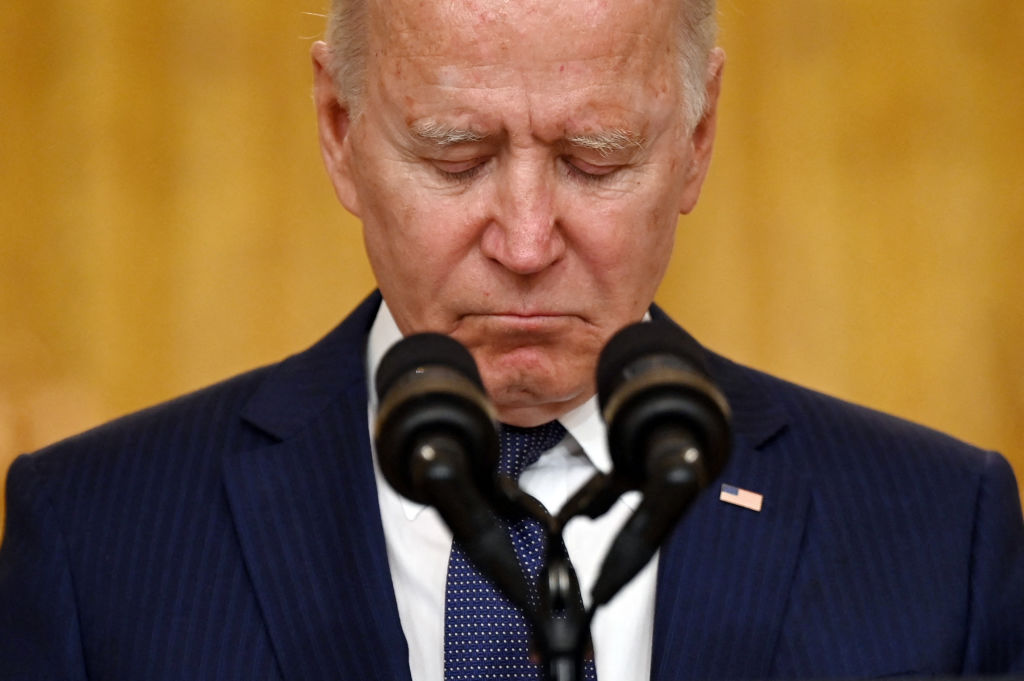

In contrast to the Journal, the Times was more sympathetic to President Biden, though most days I couldn’t see the difference. A long op-ed by former ambassador Ryan Crocker decried the administration’s ‘lack of strategic patience’ and claimed that withdrawal ‘has damaged our alliances, emboldened our adversaries and increased risk to our own security.’ Times columnist Maureen Dowd, a liberal, supported Biden’s decision, but not before she bemoaned our ‘catastrophic exit.’ If it was catastrophic, then why was it a good idea to leave? I suppose that as a member of the Washington consensus she was doing her best to keep in step with the former commander of allied forces in Afghanistan, David Petraeus, who in the Journal called the withdrawal ‘disastrous.’ Other media and political personalities were not to be outdone: ‘Shameful’ (The Week); ‘Imbecilic’ (Tony Blair); ‘Biden’s Tehran’ and ‘Dumkirk’ (New York Post).

I’m not arguing that all critics of the Afghanistan departure are necessarily fools. But the hysterical reaction to Biden’s common-sense decision to cut American losses demands more reflection and analysis. For me it recalled not so much the fall of Saigon in 1975, to which it is often compared, but rather the fall of Khartoum in 1883 and the death of Gen. Charles Gordon. Substitute the Mahdi — the religiously inspired leader of the Sudanese rebellion against Egyptian and British control — for the Taliban and we have an equivalent casus belli, with Western civilization itself besieged by the savage Islamic fundamentalism described in Lytton Strachey’s Eminent Victorians. ‘The faithful…were to return to the ascetic simplicity of ancient times’ in which criminal conduct was punishable by ‘executions, mutilations, and floggings with a barbaric zeal. The blasphemer was to be instantly hanged, the adulterer was to be scourged with whips of rhinoceros hide, the thief was to have his right hand and left foot hacked off in the market place.’ To the rescue, amidst ‘a blaze’ of popular and press excitement in England, was sent the half-mad Gen. Gordon, whose own moralistic, ascetic and religious vanity exceeded even that of Gen. MacArthur. Gordon was a liberal reformer in some respects, but he was mainly a narrow-minded adventurer of almost insane ambition — ‘ambition, neither for wealth nor titles, but for fame and influence, for the swaying of multitudes,’ as Strachey writes.

The description fits Rumsfeld, Wolfowitz and Petraeus to a T, but it also resembles the multitude of liberal interventionists who populate the US foreign affairs and media elite. Americans flatter themselves that they are not imperialists, as were so many British Victorians, and that they promote liberal values, not conquest, profit and cultural domination.

But they’re not as different from the Victorians as they believe, and their allegedly virtuous ambition remains world-straddling, in keeping with the more than 700 US military bases scattered around the globe. The good news is that Biden didn’t bend this time to America’s neo-imperialist impulse.The bad news is that he’s vastly outnumbered.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.