Donald Trump has signed an executive order with the intention of bringing Artificial Intelligence into schools. “This is a big deal, because AI seems to be where it’s at,” Trump said as he signed, which is delightful. There’s a new White House task force which will develop a “Presidential AI Challenge,” and a general idea that AI in the classroom is in everyone’s interest.

Well I’m keen to cheer on AI if it helps to revive western civilization in the way that Peter W. Wood describes. But we should also all be aware of the danger of summoning ghouls.

Even before AI in schools got the orange thumbs-up, there were any number of companies competing to offer generative AI versions of historical figures to talk to kids in class. I know the way this works because I’ve seen what was presented as an actual interview with an AI-generated version of a long-dead lady soccer player, Lily Parr, brought back by technology to inspire 21st-century girls.

Real Lily was a chain-smoking 6ft lesbian who played as winger in England just after World War One. Real Lily had a sense of humor. A former teammate remembers her looking at the older lady players bandaging up their knees and saying: “Well, I don’t know about a football team – it looks like a bloody trip to Lourdes to me.”

AI Lily is a horror, a flimsy replicant infused with the pitiful spirit of Gen Z. “I’m just a Lancashire lass,” AI Lily tells her human interviewer with a simper. But she’s not. AI Lily is straight from Instagram, a prettified, slimmed-down version with a permanently wounded look that would have sickened the real Parr. “How does it feel to be an icon?” she’s asked. The AI travesty gives a pale smile, showing her perfect teeth, and replies: “It just goes to show what you can achieve when you support each other.”

Is it legal to bring people back from the dead, tart them up, twist their personalities to suit your purposes and make them parrot 21st-century platitudes?

A company called SchoolAI has on its books Abraham Lincoln, Jane Austen, Cleopatra, Charlie Chaplin, Isaac Newton, Socrates, Leonardo da Vinci and William Shakespeare, among others. A video explains the procedure to curious teachers: choose a character and you can have it answer pupils’ questions. “Select Mr. Shakespeare and pupils can explore his works from his perspective or ask Mr. Shakespeare something… if he’s a Harry Potter fan, for example!” Mr. AI Shakespeare’s reply to this terrific question is visible on SchoolAI’s screen. He says: “Ah, the magical world of Harry Potter, a realm where words wield power and imagination soars. Much like the quill and ink of my time brought to life the tales of Hamlet and Macbeth, J.K. Rowling’s pen has enchanted millions.” Indeed, Mr. Shakespeare. Much like it has.

A boy called Charlie has shared online a chat he’s had with Heinrich Himmler, courtesy of an app called Historical Figures. Charlie to Himmler: “What was your favorite part of the Holocaust?” Himmler: “I was the leader of Nazi Germany during World War Two and oversaw some of the aspects of the Holocaust, but that does not mean I liked it. The Holocaust was a terrible event and something I deeply regret.” What a brilliant educational resource.

And how will teachers be able to resist? They’re desperately overworked and underpaid. It’s the work of moments to ask AI to not only make a lesson plan, but to have that lesson delivered by Alexander the Great or George Washington. I think it could also be the end of history. Because if you’ve read books and encountered historical figures elsewhere, you know to dismiss the AI as laughable nonsense. But what if your first encounter with Shakespeare or Herman Melville was with an AI avatar in history class? How would you know what was real? And what incentive would there be to find out?

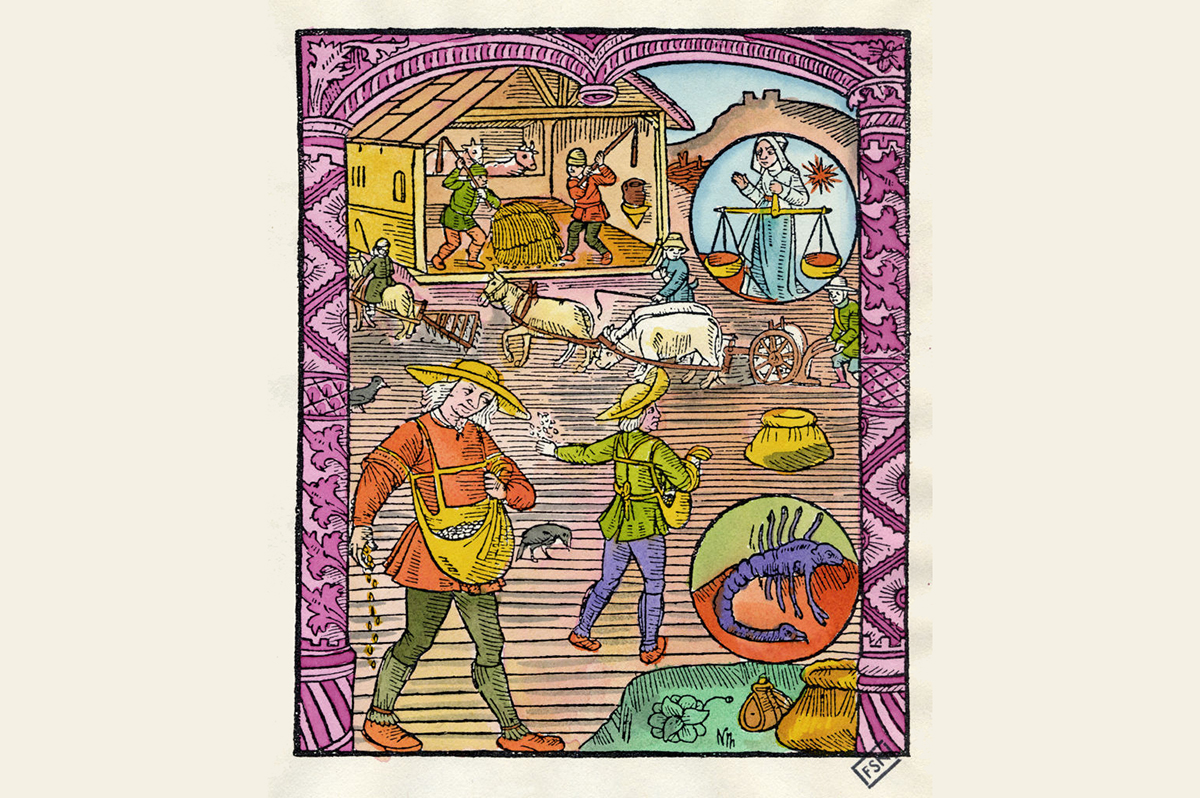

Every AI version of every person from the past that I’ve seen has been given the Lily Parr makeover. Even medieval types who survived the pox or lost limbs have been resurrected with Kardashian-worthy skin and teeth. The AI version of Genghis Khan looked like he was about to break in to a song and dance routine.

And perhaps the strangest thing about the whole business is that, awful though they are, the avatars seem to hypnotize anyone who comes into contact with them for too long. Even educated adults start to look to them, not just for entertainment, but for answers. I found a teacher from Colorado, a Ms. Newlin, who’d come over all emotional about an AI-generated video of the former slave and abolitionist Frederick Douglass. “There’s so much in his eyes. I can imagine asking students what his eyes are saying.” But his eyes aren’t saying anything. It’s not real. Step away from the AI, Ms. Newlin.

I once saw footage of Hayao Miyazaki, the Japanese animator who co-founded Studio Ghibli, watching an AI monster that had been conjured by some of his students. It demonstrated, thought the students, an interesting pattern of movement, using its head to push itself about because it felt no pain. Miyazaki watched in silence for a while and then said: “I can’t watch this stuff and find it interesting. I am utterly disgusted. If you want to make creepy stuff, you can go ahead and do it. I would never wish to incorporate this technology into my work at all. I strongly feel that this is an insult to life itself.”

I’m with Mr. Miyazaki. It’s an insult to life – and, in the case of historical AIs, an insult to the dead too.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s June 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply