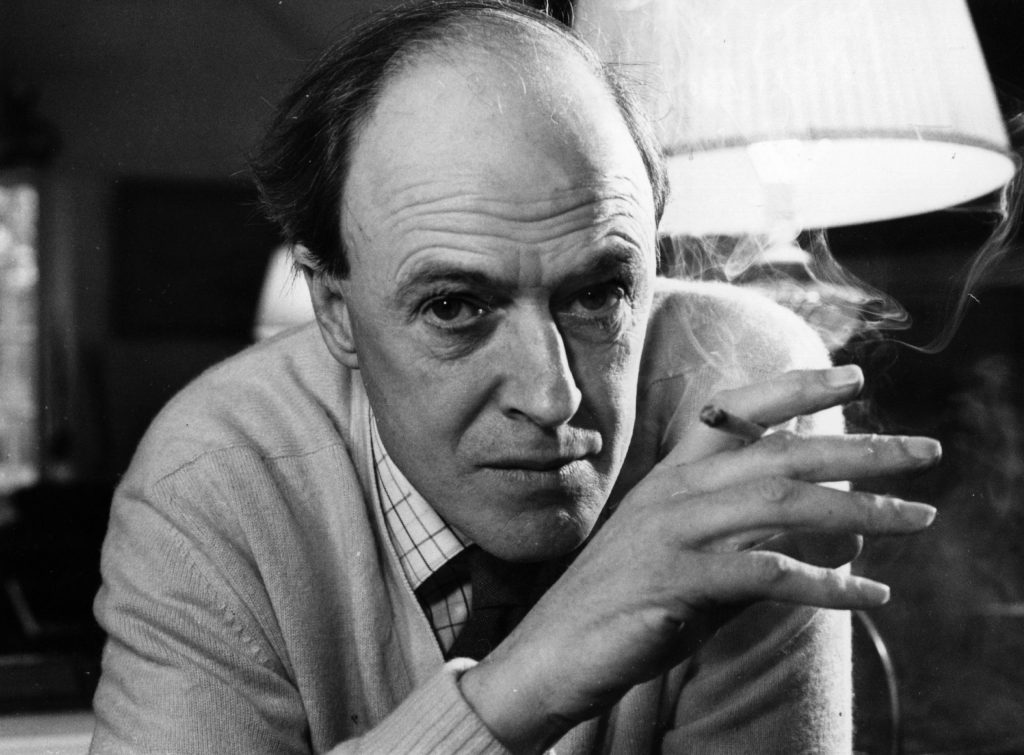

Roald Dahl died in 1990. So why does it matter today that he was an anti-Semite? Why has his family apologized 30 years on? And should his work be canceled as a result? Or, to paraphrase the Bible, should the sins of the author be visited upon the third and fourth generations who profit from his work?

In September 1983, Israeli TV stopped broadcasting Roald Dahl’s Tales of the Unexpected to avoid paying royalties to an anti-Semite, making Dahl the third person whose work was excluded from the still-young state’s airwaves after Wagner and Strauss. Dahl had just published a book review considered to be so aggressively anti-Semitic that Paul Johnson described it in The Spectator the following month as ‘the most disgraceful item to appear in a respectable British publication for a very long time’.

Writing of Israel’s actions in Lebanon, Dahl compared the Jewish state with Nazis: ‘Never before in the history of man has a people switched so rapidly from being much-pitied victims to barbarous murderers. Never before has a state generated so much sympathy around the world and then, in the space of a lifetime, succeeded in turning that sympathy into hatred and revulsion. It is as though a group of much- loved nuns in charge of an orphanage had suddenly turned around and started murdering all the children…it makes one wonder in the end what sort of people these Israelis are. It is like the good old Hitler and Himmler times all over again.’

Astoundingly, this was the softer redraft of Dahl’s views; his biographer Jeremy Treglown revealed the magazine’s editor had substituted ‘Israeli’ for ‘Jewish’.

Meanwhile, according to Dahl, America was ‘so utterly dominated by the great Jewish financial institutions over there that they dare not defy’ the Jewish state. Israeli prime ministers Menachem Begin and Ariel Sharon were ‘almost the exact carbon copies in miniature of Mr Hitler and Mr Goering’ and ‘if only Israel had stuck to her part of the bargain and been willing to share the land’ all the subsequent wars would have been avoided. In reality, Israel’s agreement to the UN partition plan had not prevented its Arab neighbors from attempting to annihilate it, as Dahl must have known.

This was not a solitary outburst. Dahl’s biographer, Donald Sturrock, describes how privately Dahl once described an American film producer as ‘the wrong sort of Jew…his face is matted with dirty, black hair. He is disgustingly overweight and flaccid though only forty-something, garrulous, egocentric, arrogant, complacent, ruthless, dishonorable, lascivious, slippery.’

The originality of Roald Dahl’s children’s stories stand in contrast to his tired and clichéd declarations about Jews. Paul Johnson wrote of the inconsistency at the center of Dahl’s anti-Semitism: ‘Like others of his kind, he attributes to Jews contradictory characteristics. On the one hand they are violently aggressive; on the other cowardly.’

It didn’t end with Israel or those he’d fallen out with. It was visceral; he attributed Hitler’s murdering of Jews to ‘a trait in the Jewish character that does provoke animosity…a kind of lack of generosity towards non-Jews… Hitler didn’t just pick on them for no reason.’ It shouldn’t need saying, but Jews have in fact contributed enormously to wider, non-Jewish society, from arts and culture to science and medicine. The collective philanthropic contribution of Jews has certainly not lacked generosity. But that is not really the point.

Dahl’s delusions saw Jews as so cunning and manipulative that they controlled, not only America, but also the entire publishing industry. He said ‘there aren’t any non-Jewish publishers anywhere, they control the media’. Yet despite Jewish dominance and power, Jews were easy to gas because ‘they were always submissive’.

[special_offer]

It’s easy to see why his children and grandchildren would want to apologize for all this. While they continue to get rich from his works — with films, musicals and merchandise based on his writing still being rolled out today — they maybe feel a burden of responsibility to condemn his insistent hostility to the Jewish people. But why did their carefully crafted 86 words of contrition take 30 years to materialize? If theirs is a genuine expression of regret, why did they hide it so carefully behind layers of easy to miss hyperlinks, and neglect to tell anyone about it?

2020 has been the year for boycotting authors for thinking the wrong things, and for tearing down statues of those with questionable pasts. A renewed sensitivity to racism has misguidedly made many people more censorious and divisive. No wonder the heirs of an unashamed anti-Semite would hope to escape the mob by covering their backs with an apology short enough to get lost in the virtual ether. While the racism wasn’t theirs, their sluggishness in condemning it undermines their sincerity in finally doing so.

Despite the growing fashion for censoring those with whom we disagree, the more wary among us are uncomfortable with the idea of casting aside Dahl’s works. He is rightly remembered as an inspiring and engaging children’s writer, but his family’s apology reminds us also of his nastiness to Jews and how objectionable it was. His example reminds us that anti-Semitic attitudes were, and probably remain, widespread among some parts of Western society. Even in otherwise polite or intellectual social milieu, views like Dahl’s resurface again and again. Though all too familiar, they must never be tolerated. They should always be challenged. They can never be excused.

This article was originally published onThe Spectator’s UK website.