“Today was hard. I can’t imagine what it was like for the families of those we left behind.”

That was an email from a friend who’d served in Afghanistan, sent as the chaos of the western withdrawal from Afghanistan played out on rolling news almost exactly two years ago.

His grief — mirrored across the military and the media establishment on both sides of the Atlantic — now feels a long time ago, at least to those detached from the twenty-year fight against the Taliban. Like many a separation, however, over time it becomes clear it was the right thing to do.

The US had spent almost a trillion dollars fighting and nation building in Afghanistan. They’d lost more than 2,000 men. And as events post-withdrawal were to quickly and tragically prove, they had little more than a Potemkin village of an Afghan government to show for all that treasure and blood.

What was the war for? The same could be asked of almost every American intervention of the last few decades. As Barack Obama’s foreign policy advisor Ben Rhodes has written:

Look at the countries in which the war on terror has been waged. Afghanistan. Iraq. Yemen. Somalia. Libya. Every one of those countries is worse off today in some fashion. The evidentiary basis for the idea that American military intervention leads inexorably to improved material circumstances is simply not there.

In the case of Afghanistan, it’s hard to argue that remaining would have made things worse. According to the UN, the country now presents the world’s biggest humanitarian crisis. Nineteen million people are going hungry. China and Russia have a free pass to the playground. And girls are banned from high schools. Sanctions were imposed in response. The ban remains. There are heartbreaking reports of girls staying on at elementary school just to keep themselves stimulated while their fellow male students move on, in the hope the Taliban will eventually allow half the population an education.

An ongoing western presence would probably have prevented some of this. But President Biden was not caught unawares by what filled the vacuum. He just didn’t think it was America’s responsibility.

According to George Packer’s magnificent biography of the diplomat Richard Holbrooke, Holbrooke tackled Biden on the fate of girls, should the US bring their boys home.

The then-vice president erupted: “I am not sending my boy back there to risk his life on behalf of women’s rights, it just won’t work, that’s not what they’re there for.”

No matter how you feel for the awful plight of Afghan women, any father is entitled to ask why his son or daughter should put his or her life on the line. The president is also entitled to ask the same question as commander-in-chief. It’s not as if oppression in other parts of the world is considered worthy of American lives.

Biden brutally — and, given the chaos of the exit, clumsily — bought Afghanistan into line with the rest of US foreign policy: the human rights of the citizens of other countries are not a casus belli.

The argument that Afghanistan is different because the West went in might hold a few years into the operation. Once a generation has passed, the point starts to lose force. “You broke it, you fix it” doesn’t quite work as justification for western involvement in Afghanistan — since the state was already dysfunctional before the war and, after twenty years of botched western fixing, it was still broken.

Even in the Obama years, Biden saw the West’s mission in Afghanistan as a ghastly case of mission creep. A surgical operation to remove al-Qaeda in the wake of 9/11 became a sprawling Wilsonian attempt at nation building — at vast cost in terms of both blood and treasure.

The Trump years offered an out-of-office Biden little reassurance that any mission had been accomplished.

Indeed, his four-year sabbatical would have given him the time to realise that re-ordering of America’s overseas priorities was imperative.

Bush and Blair went into Afghanistan not because of 9/11, but because of the threat they perceived that 9/11 represented. They saw al-Qaeda as an asymmetric challenge to the very existence of the west. Islamist ideology, allied with modern technology, made them a foe akin to the USSR — and fascism before that. That was the root of the war on terror.

On becoming president, Biden could fairly conclude that Bush and Blair were profoundly wrong.

Islamic terrorism has exacted a hideous cost in terms of human life. From Manchester Arena to Bali, passers-by have become senseless casualties. But at no stage have our institutions and societal norms been under threat. During the Cold War, Soviet tanks rolled into Budapest, Prague and of course Kabul. Entire nations were subjugated. Bin Laden was a mass murderer but never a dictator.

That is in part due to the western response. For all the talk of the failure in Afghanistan, security services have had some success in keeping mass terrorism at bay. There are recriminations when lone wolves on the radar do their worst with home-made explosives, knives, cars and at its worse in Paris in 2015 — guns. But the number of victims is now often mercifully small. In America, Congress passing tighter gun laws would save many more American lives than any number of boots on the ground in Helmand.

Biden realized — perhaps always knew — that nation states present the real danger, not cells of fanatics

Even at peak al-Qaeda in the 2000s, the global economy barely blinked. By contrast, Putin’s invasion of Ukraine has pushed the eurozone into recession, and left the UK limping along with huge debts and anemic growth. The consequences of economic stagnation are harder to quantify than a bomb in a rucksack, but it’s far from fanciful to claim that Russian troops in Kherson have led to lives lost here, as the elderly struggle to keep the heating on.

Biden realized — perhaps always knew — that nation states present the real danger, not cells of fanatics. The consequence of a Chinese invasion of Taiwan and the choking of the global semiconductor supply that might follow would be enormous. North Korea and Iran are far nearer nuclear technology than any mullah in Kandahar. The current president’s understanding of clear and present dangers is far firmer than the generation of 9/11 statesmen.

Perhaps Biden’s age — the thing most likely to block a second term — helped. He is a cold war politician. That experience gave him a context in which to better place the horror that sharked across a cloudless New York sky in 2001. Terrifying and tragic. But manageable and limited in scope.

The world of the twenty-first century is more similar to that of the twentieth than Blair, Bush et al realized. Russia, China and a handful of other states are the “enemy” that can truly scar every part of our lives. Unless we are desperately unlucky, the terrorists can’t.

Plenty of leaders could see that. It took Biden to do something about it. His opponents, those now saying he was wrong, wish he’d kept on hemorrhaging cash, blood and political capital in support of a mission that for twenty years had failed. And all the while distracting a rising superpower, China, that threatens us all.

The withdrawal itself was a mess, but it’s no easy task to end a war. Critics should acknowledge Biden’s political acumen. Biden was once warned of the political risks facing an administration that cuts and runs.

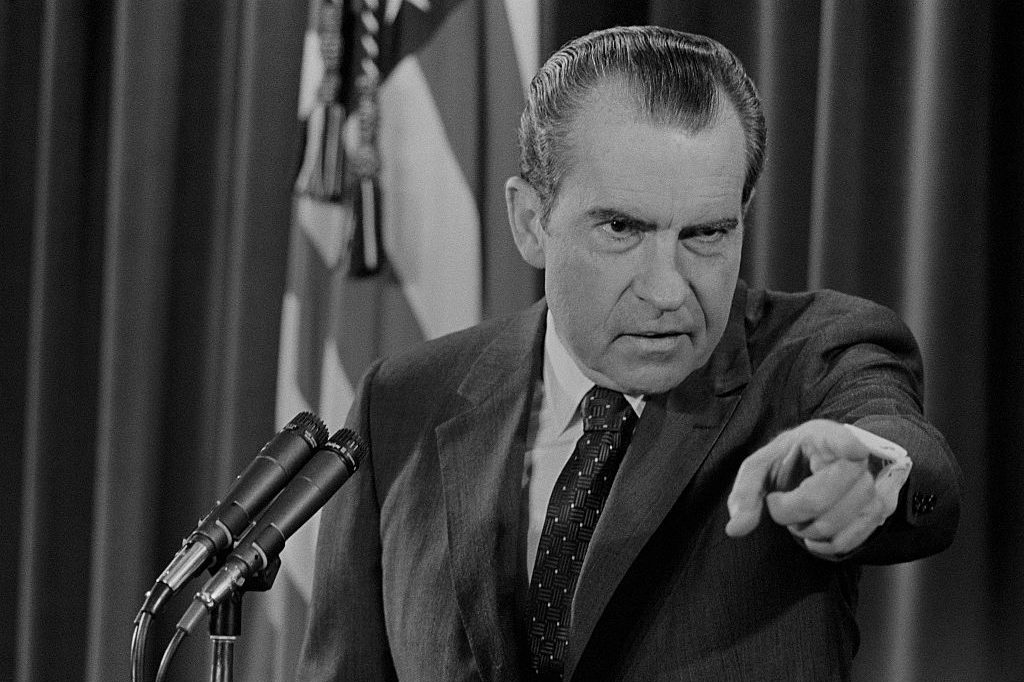

“Fuck that,” he replied. ‘We don’t have to worry about that. We did it in Vietnam. Nixon and Kissinger got away with it.”

In the weeks after August 2021, his approval rating slipped by six points. But a year after the scuttle out of Kabul, Democrats enjoyed by any standards a decent midterm result for a party holding the White House.

Afghanistan doesn’t figure in the now steady torrent of pre-2024 election analysis. Trump will swear, of course, that he never would let the Taliban seize all that American hardware or let America be so humiliated on the global stage. But, on foreign policy especially, Americans prefer to forget embarrassments. Afghanistan will not be a major talking point in the 2024 elections. That’s a point in Biden’s favor.

I replied to my friend on that day, apologizing vaguely for my insensitive inquiry as Afghans clung on to the fuselages of planes taking off from Kabul airport’s runways. I don’t really know what I’d say to him now. But I’m glad he and his men are no longer there, and the western alliance can focus on Putin and Xi, the adversaries who never went away.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.