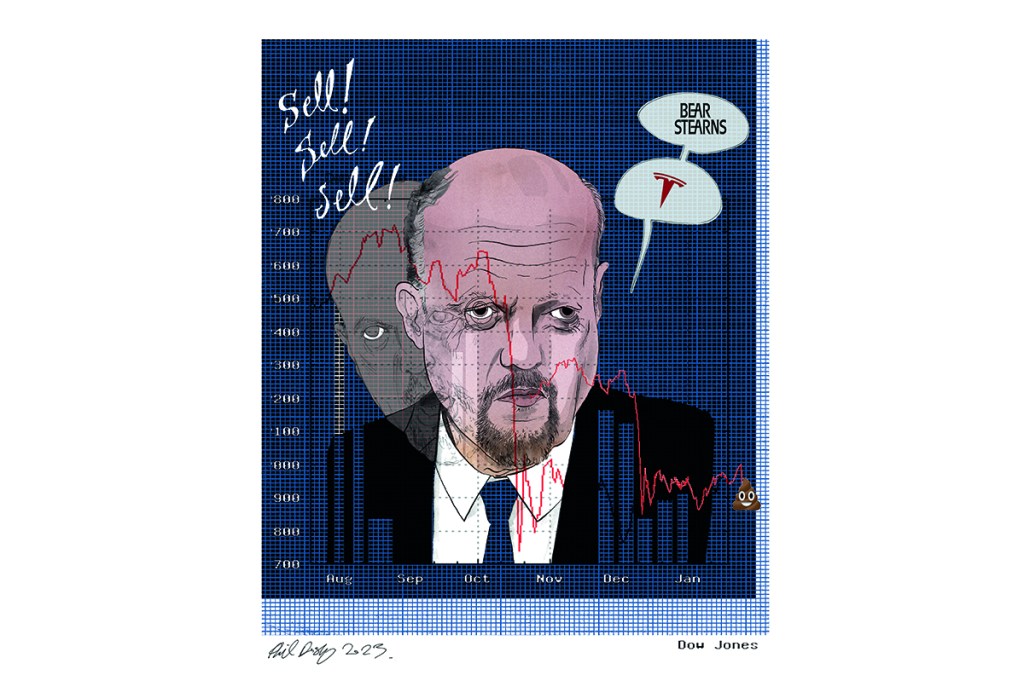

When Tesla, the electric-car company controlled by Elon Musk, went public in June 2010, pricing its IPO at $17 per share, Jim Cramer, the ubiquitous and highly confident CNBC anchor, proclaimed on his show Mad Money that investors should avoid the stock at all costs. It was a “Sell! Sell! Sell!” Cramer announced in his typical over-the-top, over-caffeinated style. But he wasn’t finished with his diatribe, not by a long shot.

“You don’t want to own this stock,” he continued. “You don’t want to lease it. Heck, you shouldn’t even rent the darn thing.” The next day, another CNBC reporter found Musk on the streets of Manhattan and told him what Jim Cramer had said about the Tesla IPO the day before: “Our own Jim Cramer said yesterday, ‘I’m not sure Tesla has a business plan that’s going to work. It’s not a smart investment.’ What do you say to the skeptics who look at where Tesla is and the money that you’re raising and say, ‘They’ve got a nice roadster, but they don’t have a good business plan?’”

Tesla’s IPO had raised some $225 million and the stock had traded up around 40 percent on its first day. Musk still had most of his dark hair back then and was obviously feeling good about things. “Well, I think, you know,” Musk responded, “as Jim might say, ‘Ya, sure, Jim, we’re no Bear Stearns.’” Burn. Major burn. Sick burn, as CNBC’s sophisticated viewers would have known all too well.

Musk was referring to the infamous moment more than two years earlier, in March 2008, when a Mad Money viewer asked Cramer if he should be worried about owning the stock of Bear Stearns, the eighty-five-year-old investment bank that was teetering on the edge of the abyss, amid wild rumors about its ongoing viability. The market had been up more than 400 points on the day, so maybe things weren’t as bad as market chatter might suggest. Responding with another patented Cramer tirade, he said, “No! No! No! Bear Stearns is fine. Do not take your money out! If there is one takeaway other than the plus 400, Bear Stearns is not in trouble! If anything, it is more likely to be taken over. Don’t move your money from Bear. That’s just being silly! Don’t be silly!”

As most everyone knew by the time of Musk’s rhetorical flourish, Bear Stearns prepared to file for bankruptcy protection a day after Cramer’s rant. And then, because of a massive intervention by the Federal Reserve, JPMorgan Chase agreed to buy Bear Stearns for $2 a share, a price that looked like a typo. Bear Stearns had avoided bankruptcy only because of the Fed-engineered rescue plan; it was the first time in American history that the Fed saved a Wall Street investment bank. Cramer had been spectacularly wrong about Bear Stearns.

Had CNBC viewers listened to him and held on to their Bear Stearns stock, they would have lost nearly everything, even after JPMorgan Chase eventually increased its offer to $10 a share. And had Mad Money’s viewers bought Tesla’s stock, instead of sell sell selling it, they would have made a small fortune, or a massive one, as Musk has. Tesla stock is up more than 13,000 percent since the IPO — and that’s after it was down around 70 percent in 2022. When Cramer reversed course a bit, saying last August, “I am all in on Tesla and CEO Elon Musk,” Musk burned him again — most likely inadvertently — by selling nearly $7 billion worth of his Tesla stock. In fact, since Cramer went “all in” on Tesla, the stock is down nearly 50 percent. Anyone who bought Tesla on his recommendation would have been singed.

But with Cramer, there’s always more. Last June, he praised Sam Bankman-Fried, or SBF, the now disgraced and incarcerated founder of FTX, as the “new J.P. Morgan” after SBF and FTX appeared to bail out several struggling crypto companies. It was not the first time Cramer gushed about a founder billionaire: in April 2015, he compared Theranos founder Elizabeth Holmes, who has since been sentenced to eleven years in federal prison for fraud, to Steve Jobs. “I regard you as a visionary, next-generation person,” he told her in a Mad Money interview.

Three days before FTX filed for bankruptcy protection on November 11, 2022, Hedgeye, an independent Wall Street research firm with some 175,000 Twitter followers, tagged Cramer’s tweet about SBF and JP Morgan. “Never before in the history of humankind has one person been so reliably wrong,” Hedgeye wrote. “@JimCramer is the anti-Midas — everything this shithead touches turns to shit.”

Or consider Cramer’s call on Meta Platforms, the company that used to be known as Facebook. On June 23, 2022, he said that shares of Meta were a buy because its CEO Mark Zuckerberg was “simply unstoppable” and that the “metaverse,” the creation on which Zuckerberg had bet billions of dollars, was “a cool place to go.” Zuckerberg had been a Mad Money guest the day before — Cramer let him blither on about the wonders of the metaverse — and the segment featured avatars of the CNBC anchors, including one of Cramer. He seemed truly moved — Zuckerberg had even created a VR garden for gardening-enthusiast Cramer to enjoy. In a conversation with his co-anchor, David Faber, Cramer gushed, “This thing is for real.” He seemed nearly overcome with emotion.

Fast forward four months, to October 27, and Cramer was again overcome with emotion, this time humility, not joy. He appeared to be nearly crying on air. Meta had just reported disappointing third-quarter earnings, and the stock fell 25 percent in one day, to the lowest level in six years. “Let me say this,” Cramer said, choking up, “I made a mistake here. I was wrong.” He said putting his faith in Zuckerberg and his management team was “ill-advised.” “I had thought there’d be an understanding that you just can’t spend and spend right through your free cash flow,” he said, “that there had to be some level of discipline.” When Faber asked him what he’d got wrong, Cramer replied: “What did I get wrong? I trusted them, not myself. For that I regret. I’ve been in this business for forty years, and I did a bad job. I’m not proud.”

A Cramer fan who has known him for decades questions just how valuable his advice is these days. “He presents himself as being the guru on every possible investment, stock, issue, and company, in a way that simply isn’t possible,” he said. “Which is why the record then reflects fundamental macro and micro errors, and then it makes you ask the question, ‘Has this descended from wisdom into carnival barker?’”

Many people seem to be wondering the same thing. In fact, there’s a new cottage industry devoted to doing the opposite of everything Jim Cramer suggests. On Twitter, the account @CramerTracker, with 170,000 followers, has been around since November 2021. Its sole purpose, it proclaims, is tracking “the stock recommendations of Jim Cramer so you can do the opposite.” I found the site’s twenty-four-year-old proprietor in Michigan — he declined to share his name — who told me that he was “always fascinated” with the idea that Cramer could go on national television “and basically say whatever he wants to say, every single day, with no accountability.”

The CramerTracker guy said he started the site to track the stocks Cramer recommended to viewers on CNBC. “But the more I spent time on it, the more I realized, like ‘Holy cow, this guy has thousands of calls each month.’ And just kind of highlighting the ones he got right and the ones he got wrong, more often than not, he hit some rock.” He decided to analyze the performance of the stocks Cramer recommended between 2017 and 2021 — his 12,564 individual calls — and compared them to the simultaneous performance of the S&P 500. The analysis showed that Cramer’s picks underperformed the S&P by around six percentage points. Not horrific, by any stretch, but far from stellar. “A little bit closer to the market than I would have anticipated,” he said.

The analysis also showed that the volume in the stocks Cramer recommended increased some 25 percent the day after: people were following his advice and promptly losing money. People think the man behind CramerTracker doesn’t like Cramer because he’s so consistently negative about him and his stock recommendations. But that’s not true. “I need him,” he tells me. “Without him, I wouldn’t have my own thing.”

James Kardatzke is the CEO of Quiver Quantitative, a company that provides traders with “unique data sets” he hopes will give them special insight into trading opportunities. He’s all of twenty-two and, like the fellow behind @CramerTracker, he’s hoping to make a living off Jim Cramer’s foibles. In August last year, he created the “Inverse Jim Cramer Strategy” and posted it on Seeking Alpha, a well-known website for traders and their ideas. “While often the target of criticism for his slightly lackluster stock-picking performance, the Mad Money host is without a doubt one of the most influential TV personalities in the history of finance TV,” Kardatzke wrote. “However, it remains a given that his stock picking abilities seem to have slowly deteriorated over the years.” Kardatzke analyzed Cramer’s ten “most recommended” 2022 stocks into August — from Procter & Gamble (#1, a loss of 10 percent) to Marvell Technology (#10, a loss of 32 percent), with Meta Platforms at #8 and a loss of 19 percent through that point in the year. All ten of the stocks Cramer touted most vociferously between January and August had lost money, not all that surprising given that the S&P 500 lost more than 14 percent since the beginning of the year.

What was surprising, though, was that Kardatzke’s inverse Cramer investing strategy — a combination of shorts and longs related to Cramer’s picks — paid off big time. For the one-year period between August 2021 and publication of the Seeking Alpha piece, Kardatzke’s trading strategy generated returns of 20.1 percent, compared to a same-time loss on the S&P 500 of 6.3 percent, a whopping 2,600-basis-point difference. Kardatzke updated the analysis in October. “Our Inverse Jim Cramer Strategy excelled even during the latter half of this troublesome year,” he wrote, again on Seeking Alpha. “The Mad Money host himself has once again proven to be a leading source of first-class investment advice, but only if we are to invert the recommendations.” In the third quarter of 2022, the inverse Cramer strategy returned 2.2 percent, while the market declined 2.4 percent, a more modest 400-basis point swing but still noteworthy.

In an interview from his home in Wisconsin, Kardatzke told me that the popularity of the inverse-Cramer strategy derives from what he sees as growing skepticism with “experts” more generally. “A lot of people are starting to become more cynical toward the idea that these are really experts who know exactly what’s going to happen and are clairvoyant when it comes to the recommendations and predictions they’re making,” he said.

Matthew Tuttle, managing director of Tuttle Capital Management, a small investment adviser in bucolic Riverside, Connecticut, has taken the inverse Cramer investing strategy further than the youngsters behind CramerTracker and Quiver Quantitative. In October, Tuttle filed a registration statement with the Securities and Exchange Commission to start trading a new ETF (exchange- traded fund) that will allow investors to bet directly against Cramer’s recommendations simply by buying the Inverse Cramer ETF — SJIM (for short Jim). The new ETF, Tuttle wrote in the prospectus, “seeks to provide investments results that are approximately the opposite of, before fees and expenses, the results of the investments recommended by television personality Jim Cramer.” At least 80 percent of the ETF’s investments will be invested “in the inverse of the securities mentioned by Cramer,” he wrote, by either shorting the stocks he recommends or by entering into derivative contracts that “produce a negative correlation” to his on-air recommendations. While Tuttle appears to be an equal opportunity ETF advisor — he’s also pushing a “Long Cramer” ETF (LJIM) — his heart seems to be on the inverse side. Tuttle has been a Wall Street trader since 1999 and says he’s a “huge believer” that individual investors need to educate themselves about Wall Street and the financials of individual companies. “Just look at all the crap that goes on out there,” he told me.

One place individual investors go to educate themselves are the financial news networks, such as CNBC, Fox Business and Bloomberg. But Tuttle worries about the quality of their content. “What financial media has turned into is entertainment and I get it, it’s ratings,” he said. “Look who the advertisers are… I wouldn’t mind that as much… if they labeled it as such.” He’s especially miffed that CNBC gives Cramer free rein to make his recommendations and then rarely holds him accountable when they prove disastrous. “When Jim Cramer comes on, they treat him with deference: ‘Hey, we’re going to bring Jim on and ask him what he thinks about this,’” Tuttle continued. “And there is never, ‘Hey, Jim, yesterday we asked you about what you thought about SNAP earnings and you said SNAP was going to be great. And right now, it’s down 30 percent. Did you get that one wrong?’ And there’s never any of that;” — actually occasionally there is — “there’s amnesia on what he said the previous day and the previous day before that. And there’s never a disclaimer on the bottom ‘Hey, this is just entertainment,’ which there clearly should be on Mad Money.”

For its part, CNBC, where I’m an occasional contributor, declined to make Cramer available to be interviewed in a timeframe to meet The Spectator’s deadline, nor did it allow me to speak to any of his CNBC colleagues or make introductions for me to his friends. “Cramer isn’t inclined to be interviewed,” Keith Cocozza, the CNBC spokesman, said in an email to me.

Jim Cramer, now sixty-seven, was a wunderkind. He grew up in a suburb of Philadelphia. His mother was an artist; his father owned a packaging company. As a teenager, he hawked Coca-Cola and ice cream at Veterans Stadium. At Harvard, he studied government and rose to become president and editor-in-chief of the Harvard Crimson. Along with his occasional beefs about the Harvard curriculum, most of Cramer’s Crimson pieces were about jazz.

After graduating in 1977, Cramer worked as a newspaper reporter in Tallahassee and Los Angeles, where he wrote obituaries for the Herald-Examiner. He lived out of his car for nine months after his LA apartment was robbed. In 1981, Cramer enrolled in Harvard Law School. He started trading stocks while there, leaving stock tips on his answering machine and making enough money to pay tuition. Then it was time for connections to kick in. Michael Kinsley, a fellow Harvard alum, introduced Cramer to Marty Peretz, the owner of the New Republic — Cramer’s sole article for the magazine, in November 1977, was about the importance of meritocracy in the National Football League, specifically at his beloved Philadelphia Eagles. Peretz also made money from some of Cramer’s answering-machine recommendations and gave Cramer $500,000 to invest; he made Peretz $150,000 over two years.

After graduating from Harvard Law, and a brief stint as a clerk for Alan Dershowitz, who was defending Claus von Bülow, Cramer joined Goldman Sachs in the sales and trading department. (He passed the bar but never practiced law.) After three years, he left Goldman to set up his own hedge fund with some $450 million of investors’ money. In addition to Peretz, the early investors were Steven Brill, the owner of American Lawyer, for which Cramer had written, and his law school classmate Eliot Spitzer, later attorney general and governor of New York. He ran his firm until 2001, when he retired from the hedge fund business. He told BusinessWeek in 2005 that he had averaged returns of 24 percent annually and taken home annual pay in excess of $10 million.

Cramer also had some side interests. In 1996, he and Peretz started TheStreet.com, a website dedicated to financial news and investing. Cramer took it public in May 1999, before the internet bubble burst, and made a small fortune. He was an editor-at-large for SmartMoney. He appeared frequently on CNBC. In 2002, he teamed up with Larry Kudlow, the former Bear Stearns economist and future national economic adviser under Donald Trump, to host Kudlow & Cramer on CNBC. In March 2005, Cramer started Mad Money, his own CNBC program, to better educate the growing class of lay investors. It quickly became CNBC’s most watched show, with some 380,000 viewers tuning in every weeknight as of November 2005. (In November 2022, only about 147,000 people watched Mad Money; it’s no longer among CNBC’s ten most popular shows.)

Cramer was getting famous. In November 2005, Dan Rather interviewed him on 60 Minutes. “He’s the Jerry Lewis of business show hosts and he will do anything to grab your attention,” Rather said. He got Cramer to admit that he had been wrong about recommending that people buy the equity of Dick’s Sporting Goods. “I blew it,” he told Rather. “I blew the call. And I think you have to own up to ’em, admit ’em.” He also became infamous when he appeared on The Daily Show with Jon Stewart in March 2009, a year after Bear Stearns’s collapse and Cramer’s spectacularly wrong call. Stewart chewed him up and spit him out, to the delight of a studio audience more than a little angry at Wall Street. “I understand you want to make finance entertaining,” Stewart told Cramer. “But it’s not a fucking game.” In the midst of his ongoing beating, Cramer finally conceded he should have done more to foresee the financial crisis and to warn people about it. “I can’t reconcile the brilliance and knowledge that you have of the intricacies of the market with the crazy shit I see you do every night,” Stewart concluded.

In fairness, Cramer has made a few smart calls. He was an early booster of the chip makers Nvidia and Advanced Micro Devices. He recommended both around May 2020 and both stocks have performed well. Nvidia has more than doubled (and at one point was a five-bagger for Cramer) and AMD is up roughly 25 percent. “My dog is named Nvidia and he’s about to hit an all-time high!!” Cramer tweeted in June 2018. He also saw trouble coming in the Disney C-suite early and called for the removal of CEO Bob Chapek the day after Chapek announced Disney’s fourth-quarter earnings and Disney stock fell 13.2 percent. Cramer texted the Disney CFO, Christine McCarthy, with his view that the results were “devastating” and then said on CNBC the next morning that Chapek should “absolutely” be fired, that he was “delusional” after presenting Disney poor earnings as pretty wonderful. Eleven days later, Cramer was proven right when the Disney board kicked Chapek to the curb and replaced him with former CEO Bob Iger. It was McCarthy who got the ball rolling, according to the Wall Street Journal.

In January 2022, Cramer started the CNBC Investing Club. For $400 a year, the general public can attend virtual monthly club meetings, with access to Jim Cramer and the portfolio of his charitable trust, as well as live daily Cramer videos, daily news and analysis and a newsletter. “The exclusive investor-focused product will equip members with Cramer’s unparalleled knowledge and analysis of portfolio management and investing and give behind-the-scenes access to Cramer and the Investing Club team,” CNBC boasted at the time of the launch. Members of the club also get access to the trades he makes in his charitable trust portfolio forty-five minutes before he makes the trade or seventy-two hours before he makes the trade if he mentioned the stock on CNBC. (Cramer’s trust has made $3.8 million in charitable donations since he formed it in 2005.) Observers assume that Cramer himself takes a piece of the subscription fees that come into CNBC for the Investing Club. “He tweets about it every other day,” the @CramerTracker guy tells me. “That’s one thing I always thought was unethical.” (Cocozza, the CNBC spokesman, declined to comment about the Investing Club.)

Right or wrong, ratings high, ratings low, Cramer endures after two decades on CNBC. It must be because people still watch and he must still make money for the network and its parent company, Comcast. (Cocozza declined to comment about whether Cramer is a CNBC money maker.) “He’s brilliant,” Spitzer tells me. “He was a friend. His brilliance was unambiguous.” Spitzer also said he was a happy investor in Cramer’s hedge fund. “He was an all-star year after year,” he continued. But, Spitzer continued, maybe the original formula has hit some headwinds. “Later in his career, maybe he’s batting .250,” the former New York governor said, “and you wonder whether the world has changed, the markets have changed, information flows have changed and the forum has changed. And, so, he’s now on TV rendering advice instantaneously in response to questions… But it’s a tough market and whether that is a way for people to make investment decisions is a serious question in my mind.”

One thing is certain, though: Cramer remains hard to take your eyes off, if wild-ass, carnival-barking stock picks are your thing. “He comes on, and he’s forceful and confident,” Tuttle told me. “If I were running a news network, and we were looking for someone on there to be entertaining, he is perfect for that. [But] if they ever did have accountability, they’d have to get rid of him.”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s February 2023 World edition.