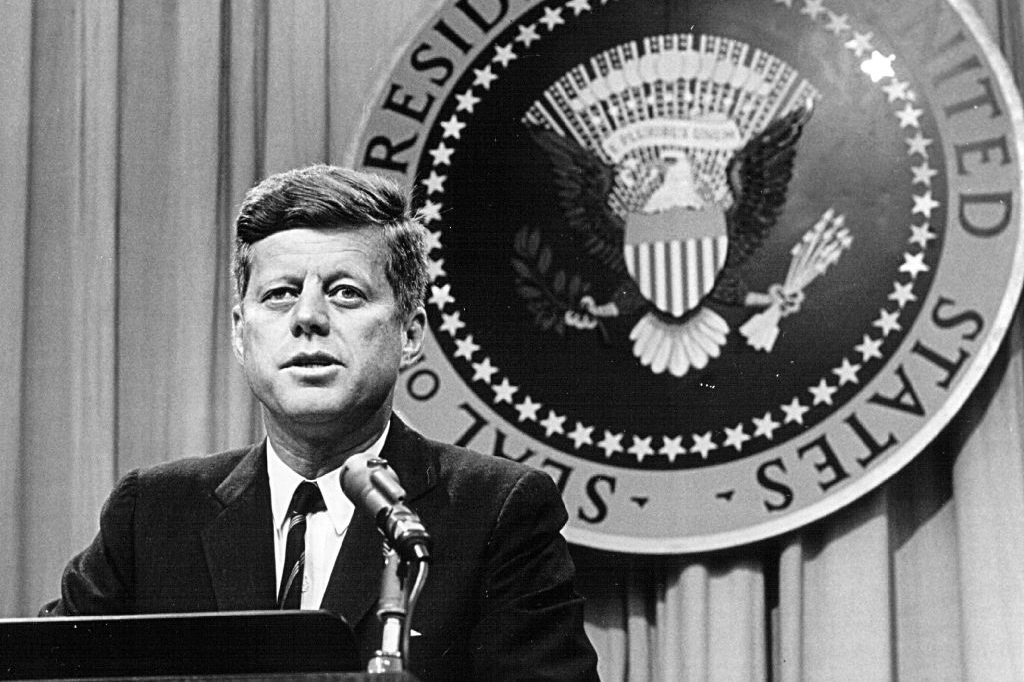

How should we assess the value of a US president? In the case of John F. Kennedy, who died sixty years ago, the box denoting youthful vigor clearly gets a checkmark. Kennedy was just forty-six at the time of his assassination, which makes him younger than Hunter Biden is now. The box denoting the “vision thing” gets checked as well, if only because Kennedy saw the potential for beating the Soviets in the race to put a man on the moon, famously declaring, “We choose to do this, not because [it is] easy, but because it is hard; because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills.”

Also to be considered is the collective trauma of the events of November 22, 1963. Early death is often seen as a kind of martyrdom, and Kennedy’s murder in Dallas that unseasonably warm fall afternoon would be widely portrayed that way, with a lively internet-fueled debate that continues to grapple with the idea that a “lone nut” could have succeeded where a lifetime of serious illnesses, debilitating surgeries and violent wartime contact with a Japanese destroyer — let alone the subsequent burdens of office — could have failed.

But was JFK actually any “good” as a president? That may be a more difficult question to answer.

To descend first into the briar-patch of the 1960s civil rights movement: Kennedy was not a natural champion of the campaign to abolish legalized racial segregation, discrimination and disenfranchisement. Prior to assuming office in January 1961, his only real contact with individuals of color had been with the uniformed men and women who stood deferentially behind him at the dinner table or opened and closed car doors on his behalf. But he was a pragmatist, and above all a believer in stability. “This will give [African Americans] another remedy in law,” Kennedy told aides when coming to consider a civil rights bill in May 1963. “It will remove [the incentive] for mob action.”

Perhaps the one tangible legacy of Kennedy’s stirring inaugural speech about asking not what your country can do for you was the creation of the Peace Corps, which within a year saw 7,000 volunteers serving in forty-four underdeveloped nations around the world. As an initiative it fell some way short of JFK’s call to end global poverty, but it was a worthwhile endeavor that survives on a mere $410m annual budget today, if not so much to feed the hungry as to implement what it calls its “roadmap to intentionally improve a Sexual Assault Prevention and Response Program through bolstered systems, procedures and trainings.”

A conservative both when it came to spending his own money and the taxpayer’s, Kennedy obsessed about the nation’s balance-of-payments deficit, which again triggered his fears of social instability. If foreign holders of US dollars exercised their right to convert them into gold, his reasoning went, the result could be a catastrophic run both on US bullion reserves and retail banks. “It’s a club that [foreign leaders] always hold over my head,” he told his aide Ted Sorensen. “Any time there’s a crisis or a quarrel, they can cash in all their dollars and then where are we?”

Kennedy rarely cared to dwell on the minutiae of the federal budget, which he sensibly left to others, although he did have one practical suggestion to make about reducing the outward flow of US currency to European capitals by keeping his father at home and encouraging his wife to see America first.

Kennedy’s foreign policy also perhaps failed to match the heady rhetoric of his inaugural speech, in which he declared, “We shall pay any price, bear any burden… in order to assure the survival and the success of liberty.” In fact, it was characterized by two early fiascos. The first was the aptly-named Operation Bumpy Road, as the abortive CIA-backed invasion of Cuba was known. That was bad enough, but the agency’s parallel attempts to sabotage Fidel Castro’s revolution by means such as supplying him with an exploding cigar, a poisoned wetsuit or an LSD-spiked drink read like a luridly melodramatic Mission: Impossible script as interpreted by the Marx Brothers. Just two months later, Kennedy then returned from a “very sober” meeting with Nikita Khrushchev in Vienna, the moment at which he came to appreciate the limits of youthful charm when doing business with a high-functioning psychopath, to ask Congress for a further $3.3 billion military buildup.

Kennedy exercised commendable restraint at the time of the Berlin Wall’s appearance in August 1961, noting only that the so-called Anti-Fascist Protection Device showed “a sad disregard of the desire of mankind for a decrease in tensions.” (The president’s private remarks on the subject betrayed more of his old life in the navy: “Fucked again,” he told aides when informed of the initiative.) Fourteen months later, Kennedy famously called Khrushchev’s bluff over the latter’s deployment of ballistic missile bases in Cuba, while quietly agreeing to remove the US’s analogous PGM-19 Jupiter rockets stationed at Izmir in Turkey, about 400 miles (or two-and-a-half minutes’ flight time) from the southern coast of Russia. In a related development, Kennedy and his British counterpart Harold Macmillan later concluded a partial nuclear test ban treaty with the Soviets, which its proponents hailed as a significant thaw in East-West relations, if not the beginning of the end of the Cold War.

Historians are left to speculate whether a continued Kennedy presidency would have approached the deteriorating situation in Vietnam differently from its successor. Events under President Johnson were to move more quickly than anyone, including Johnson, could have anticipated. But we know that by the fall of 1963 Kennedy had privately concluded that the Saigon regime of President Ngo Dinh Diem was incapable of defeating the communist incursion from the north. Some of Diem’s generals felt the same and engineered a coup against him on November 1. Diem was placed in an armored car and then clubbed and hacked to death in an act of carnage that might have shocked the Manson family. Taping a statement for the record two days later, Kennedy was contrite: “I feel that we [at the White House] must bear a good deal of responsibility for it,” he said, “beginning with our cable in which we suggested the coup. In my judgment, that wire was badly drafted. I should not have given my consent to it.”

We needn’t linger over the details of Kennedy’s private life, nor those of his marriage, which as the world knows strayed from the traditional monogamous ideal. (At the end of a lengthy discussion of the dry arcana of Britain’s independent nuclear deterrent, the president turned to the elderly Macmillan and enquired: “I wonder how it is with you, Harold? If I don’t have a woman for three days, I get a terrible headache.”) Paradoxically, Kennedy loathed being touched or embraced, a phobia he shared with Richard Nixon, and showered and changed his clothes compulsively, often five times a day. In later and less reticent times, several of his partners noted that the act of union had tended to be brisk. “He didn’t even take his shoes off,” one companion sighed.

While we’re in the realm of conjecture about what America’s essentially pragmatic thirty-fifth president might have made of the present-day Democratic party, it’d hard to believe he would have seriously disagreed with the words of his nephew Robert F. Kennedy Jr.: “Being a Kennedy Democrat means standing for freedom, and an equitable nation where if people work hard and play by the rules they can get ahead, and where the middle class isn’t being gutted to pay for bank bailouts and useless lockdowns.”

Leave a Reply