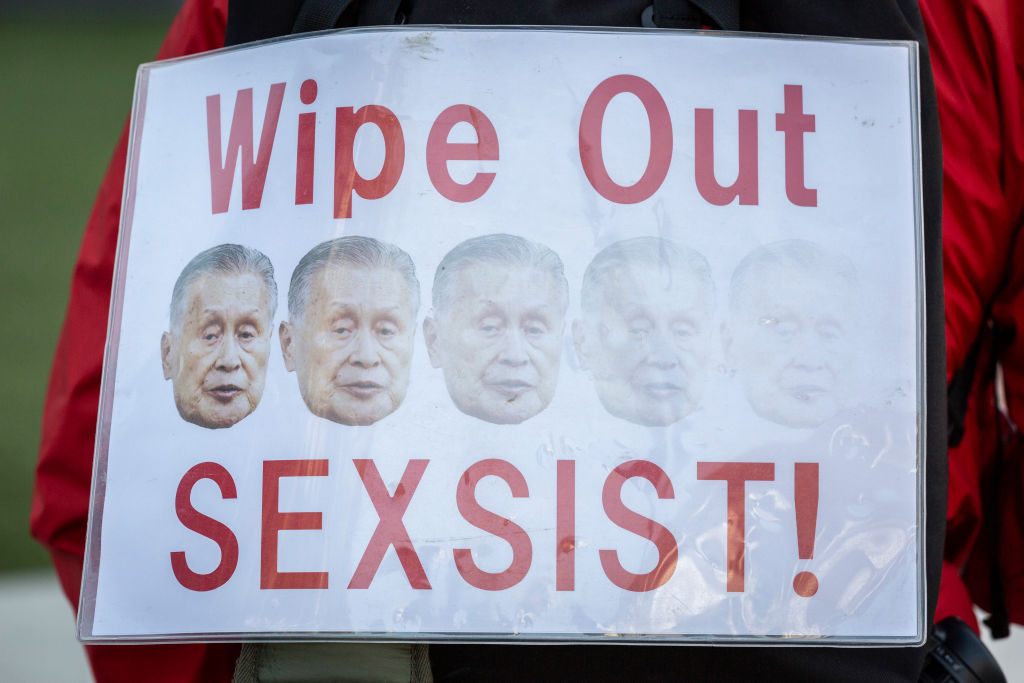

Yoshiro Mori the 83-year-old former Japanese prime minister has resigned from his position as president of the Tokyo Olympic Organizing Committee less than six months before the games are due to start. Mori’s crime? Making spectacularly unwise comments during a discussion of how to increase women’s representation on the committee.

‘When you increase the number of female executive members, if their speaking time isn’t restricted to a certain extent, they have difficulty finishing, which is annoying,’ he was reported as saying.

Along with a litany of other problems and embarrassments, Mori is the second senior Olympic official to quit due to a scandal. Mori-gate bookends neatly the resignation of the former president of the Japanese Olympic Committee Tsunekazu Takeda over corruption allegations connected to Tokyo’s initial bid. An unnamed government source recently described the Tokyo Olympics as ’doomed’. Perhaps he should have said cursed.

The story being spun about Mori is that he a relic of a bygone age with hopelessly archaic attitudes. With a typically elitist sense of entitlement, he tried to cling on, but has been toppled by the escalating pressure of a ‘Mori must fall’ campaign that has united Japanese society in progressive indignation.

In fact Mori, who quickly apologized, albeit in a cack-handed fashion, for his daft comments, had signaled he was prepared to go. But he received high-level support, first from prime minister Yoshihide Suga and then from Liberal Democratic party secretary-general Toshihiro Nikai; both urged him to get on with delivering the games. Toshiro Muto, managing director of the organizing committee joined ‘others’ in supporting the under-fire Mori, according to the man himself.

Dick Pound of the IOC accepted Mori’s apology, called the matter settled, and declared it time to move on. But was Mori right to go?

Outright condemnation was initially very hard to find: even Tokyo governor Yuriko Koike, the highest-profile female politician in the country, who has a track record of bickering with Mori over games-related matters, was uncharacteristically restrained in her criticism. Koike did say Mori’s comments left her ‘speechless’, which prompted the quip that this might have been what Mori intended all along, but she didn’t call for his resignation.

And nor did Yuko Inazawa, the woman who believes she may have inspired Mori’s comments. Inazawa, the first female member of Japan’s Rugby Football Union, which Mori headed for 10 years, condemned Mori’s ‘unconscious bias’ but said that he had never behaved in a discriminatory manner during his and her time at the JRFU. Then she undermined her own argument, unconsciously perhaps, by admitting that she had indeed taken up quite a lot of speaking time in the committee, as she had no detailed knowledge of the sport and had asked questions from the standpoint of an amateur.

Much has been made of a petition initiated by student activists that attracted 150,000 signatures. But it only called for Mori’s censure, not his resignation or dismissal. Much has also been made of a number of Olympic volunteers who resigned in apparent disgust. But readers of the small print will notice that the resignations were for ‘all reasons’. No figures have been given for how many volunteers of the deeply troubled games had quit pre-Mori-gate, so it’s unclear how many were outraged by his comments into doing so.

Tennis star Naomi Osaka, who has spent a lot of her time recently allying herself with political causes — she sported a ‘George Floyd’ headband at a recent tournament — has condemned Mori’s comments. But no other prominent Japanese sports stars have joined her.

So what’s really going on here? This kind of identity politics driven pile on is not common in Japan. And it goes against the grain to demand the head of a former PM on the basis of off-the cuff comments, however offensive they are deemed to be. The normal pattern would be a quick apology and a bow of the head, and then we could all move on.

And that is probably what would have happened here, but then the corporates started to weigh in. The already jittery big firms, who fear their massive investment in the games may turn out to be a complete waste of money, are ultra-sensitive to the image of the event their logos may soon adorn. Toyota, Asahi and Eneos all issued statement condemning Mori’s remarks.

That changed the mood. All of a sudden, the formerly ‘indispensable’ Mori became dispensable, and he was bundled out the exit door before the issue could metastasize and the multinationals take fright. A sponsors’ revolt really would be the end of the games.

Mori is hugely experienced and very well connected in the world of sports administration. He has a good track record — he’s credited with securing the 2019 Rugby World Cup for Japan and is generally considered to have done a difficult job at the committee well. It might have made much more sense for him to eat some more humble pie, serve out his term quietly, and then hand on the torch.

But now he’s gone, and all this story proves is who’s really in charge of international sport. Meanwhile, amidst the small matter of the ongoing pandemic, it remains to be seen whether the Olympics will even go ahead at all.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.