After three weeks of airstrikes, Israel has begun its ground invasion of the Gaza Strip. The goal, in the words of the defense minister, Yoav Gallant, is to “wipe them [Hamas] off the face of the Earth.” But without a long-term political vision, this objective is unachievable. Even if Israel deals a powerful blow against Hamas, the country risks becoming trapped in a long and costly war that will cause a dangerous blowback across the Middle East.

The whole region could easily spiral out of control, potentially directly dragging in the US and Iran

For now, Israel is concentrating on northern Gaza — which it sees as Hamas’s beating heart. This will be a bloody fight and the street-to-street combat could last for months. As Israeli forces move deeper into the Strip, they will face a determined and well-armed adversary who will use the urban landscape to its advantage.

According to one source close to the leadership, Hamas’s military wing, the Izz al-Din al-Qassam Brigades, which appears to have orchestrated the October 7 attack on Israel, has been preparing for this moment for five years. The CIA estimates Hamas has between 20,000 and 25,000 fighters on the ground in Gaza. It also has the support of other armed groups, most notably Islamic Jihad — another Iranian-funded organization.

A crucial part of Hamas’s defenses is its sprawling network of underground tunnels beneath Gaza, called “Gaza Metro” by the Israeli military, which reportedly totals some 300 miles. The tunnels allow Palestinian fighters to move around the Strip in relative safety and to ambush advancing soldiers. It’s also the hiding place for many of Israel’s top targets, such as Mohammed Deif, the leader of the al-Qassam Brigades. He has survived several assassination attempts and it is now believed he spends all of his time underground. Since Israel’s siege began, Yahya Sinwar, Hamas’s leader in Gaza, has also escaped into the bunker system.

Locating all of Gaza’s tunnels will be a huge task for the Israelis, and there is little precedent for the kind of close-quarter tunnel warfare that’s required to capture Gaza Metro. The Israeli army has spent time preparing for tunnel warfare by developing new drone technology and advanced sensors which can detect objects deep beneath the ground. The US military also dispatched a three-star general, James F. Glynn, who led the fight against ISIS in Mosul, to provide additional expertise. But even with these advanced systems and American military advice, Israel will still have to risk its soldiers in an unknown subterranean battlefield. The military will prefer to try to destroy as many of the tunnels as they can from above ground, but this will be tricky given how deep some of these are (reports suggest they can descend to as far as 230 feet). Blowing them up will also result in further massive destruction to Gaza’s civilian population and infrastructure — as well as endanger the Israeli hostages being held underground.

As troops prepare to go underground in Gaza, Israel also faces the very real risk of a bigger conflict breaking out on its northern border. Since October 7, Hezbollah, Lebanon’s dominant militant actor, which is also backed by Iran, has been launching limited attacks on Israel in the north in a show of solidarity with Hamas. Hezbollah secretary-general Hassan Nasrallah has warned that his troops — who number at least 60,000 and are far better trained and armed than Hamas — will intervene more forcefully if Israel launches a full ground operation. Already Hezbollah has been targeting Israeli bases, towns, and military vehicles near the border — leading to retaliatory strikes by Israel against its positions. Both sides appear to have suffered casualties.

Were a full-fledged war to break out on the northern front, the whole region could easily spiral out of control, potentially directly dragging in the US and Iran. The US has sent two aircraft carriers to support Israel and has signaled to Iran that it will take military action if the conflict widens. But behind the scenes the US is lobbying the Israelis not to open up a second front. Since October 7, Iranian-linked militias in Syria and Iraq have already attacked US forces based in both countries, prompting retaliatory American airstrikes. The Israelis have continued to launch attacks on Syrian bases, including Damascus and Aleppo airports, to prevent Iranian weapon shipments to the Lebanese armed group. On October 19, a US navy destroyer also intercepted cruise missiles and drones launched by Iranian-supported Houthi rebels in Yemen — more than 1,000 miles away. More have been fired since, with a Houthi military spokesman promising more to come “until Israeli aggression stops.”

At the same time, images of death and destruction in Gaza are hardening anti-Israel attitudes among the broader Arab public. While Arab leaders are privately lobbying for cool heads to prevail, there are massive protests in Middle Eastern cities in support of Gaza. Further afield a mob gathered at Makhachkala airport in the mainly Muslim Republic of Dagestan over the weekend, looking for Jews to lynch.

If Israel’s military challenge is hard, the political challenge may be even harder. Israel has so far avoided spelling out what comes after the ground operation. But even if Israel does succeed at tremendous cost in eliminating Hamas’s leadership and thousands of its fighters in Gaza, it will not be able to fully uproot the movement. It should be remembered that Hamas was founded in Gaza in 1987 when the Strip was under direct Israeli rule. Its social, religious and activist networks, established over the subsequent decades, run deep.

The West Bank is quickly sliding into a third intifada — uprising — against Israel

Hamas is also more than just Gaza. Whatever happens, it will continue to exist as a significant Palestinian political and armed movement: you cannot just wipe out an ideology. Most of its senior leadership is based abroad. Some live in Qatar, others under the protection of Hezbollah in Lebanon. For now, they remain out of Israel’s reach.

Support for Hamas will also grow in the Israeli-occupied West Bank, where it acts as a counterweight to Mahmoud Abbas and his ruling Fatah Party. While it is not as strong there, militarily speaking, compared with Islamic Jihad and Fatah’s al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigades, it has seen a surge of public support since the beginning of the war. Were elections to be held today, Hamas would undoubtedly win, given the deep unpopularity of the Palestinian Authority leadership. Against the backdrop of surging Israeli settler violence, the West Bank is quickly sliding into a third intifada — uprising — against Israel.

Hamas also has a substantial presence in the Palestinian refugee camps of southern Lebanon, from where it has launched many attacks against Israel. Last April, the Israeli military linked it and Islamic Jihad to a series of rocket attacks against northern Israeli towns. Hamas has launched more such attacks and border raids over the past few weeks. It has also re-established a presence in Syria since mending relations with Bashar al-Assad’s regime last year. This will potentially provide it with a new front from which it can threaten Israel. Indeed, there have already been several attacks from there against the Israeli-occupied Syrian Golan Heights.

Faced with these immense challenges, Israel appears to be recalibrating its goals to avoid getting caught up in an open-ended conflict. Instead of fully reoccupying the Strip, Israel may try to seal its borders once its immediate objectives are met, replacing the current fence with a West Bank-style wall and permanently closing all crossings. In doing so, the Israeli government may see an opportunity to deepen Gaza’s separation from the West Bank, blocking any future prospect of reaching a two-state solution. In such circumstances, it is doubtful whether the PA or any international peacekeeping mission would step in to administer Gaza if Hamas is unable or unwilling to do so.

What’s more, Israeli officials have said that the densely packed Strip should have less territory. In practice, this means expanding existing buffer zones deep into Gaza, effectively creating no-go areas for Palestinians. Gaza would lose large parts of its agricultural land, and towns close to the edge of the Strip, such as Beit Hanoun and Beit Lahia in the north, might be leveled, displacing tens of thousands of residents.

Of course Israel has a right to self-defense according to international law. But there is no long-term military solution to the threats it currently faces. The fact that Israel has no good options is in large part the tragic consequence of the actions of successive Israeli governments, which have eroded any political track for a two-state solution.

Israeli authorities have also repeatedly dodged any serious effort to develop a political vision for Gaza, one that could have strengthened moderates who advocated for political engagement. Instead, Israel pursued a policy of weakening more moderate Palestinian leadership and fell for the dangerous illusion that Gaza and its Hamas rulers could be managed through a series of fragile ceasefire arrangements that perpetuated what ultimately proved to be an unsustainable status quo. As one Israeli intelligence official remarked a few years ago: “We feel like we have a better relationship with Hamas than we do with the PA.”

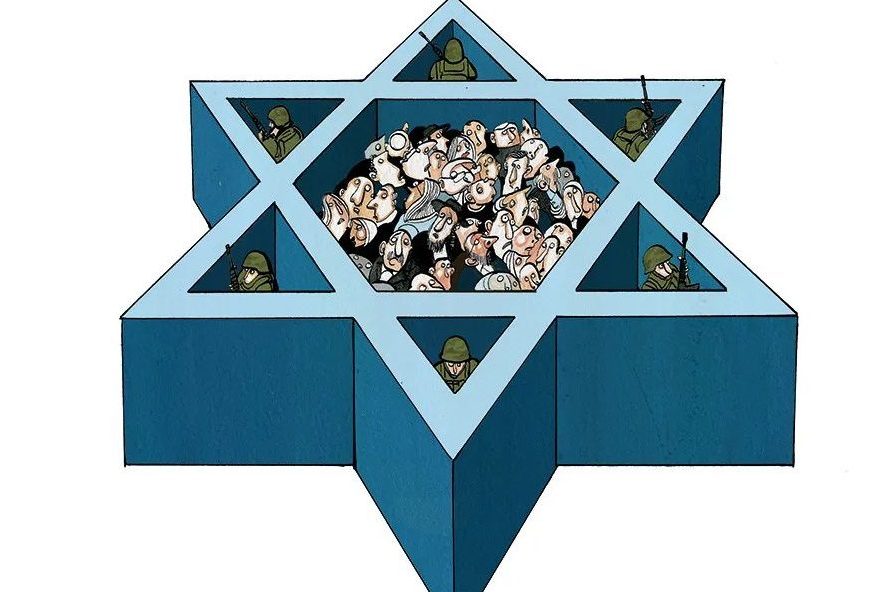

No matter how difficult it is for Israel to accept, long-term peace and security for Israelis will only come through a negotiated political agreement that ends Israel’s metastasizing occupation and enables Palestinian self-determination. Without this, both sides will stay forever trapped in a cycle of violence.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply