“ISIS is taking huge advantage of the current situation in Syria,” Ilham Ahmed told me, when we met in the north Syrian city of Hasakeh in mid-January. “In the recent time, there have been many attacks on checkpoints of the SDF (Syrian Democratic Forces). They are most active in the al Badiya area. There’s no security control there, and we have confirmed intelligence information of plans for an attack on the al-Hol camp to liberate the families there.”

Ahmed chairs the foreign relations department of the Autonomous Administration of North East Syria (AANES). This is the Kurdish-dominated de facto government with which the US and its allies aligned during the war against ISIS’s self-declared “Caliphate” between 2014 and 2019. That war was successfully prosecuted and ended with the fall of the town of Baghouz in the summer of 2019.

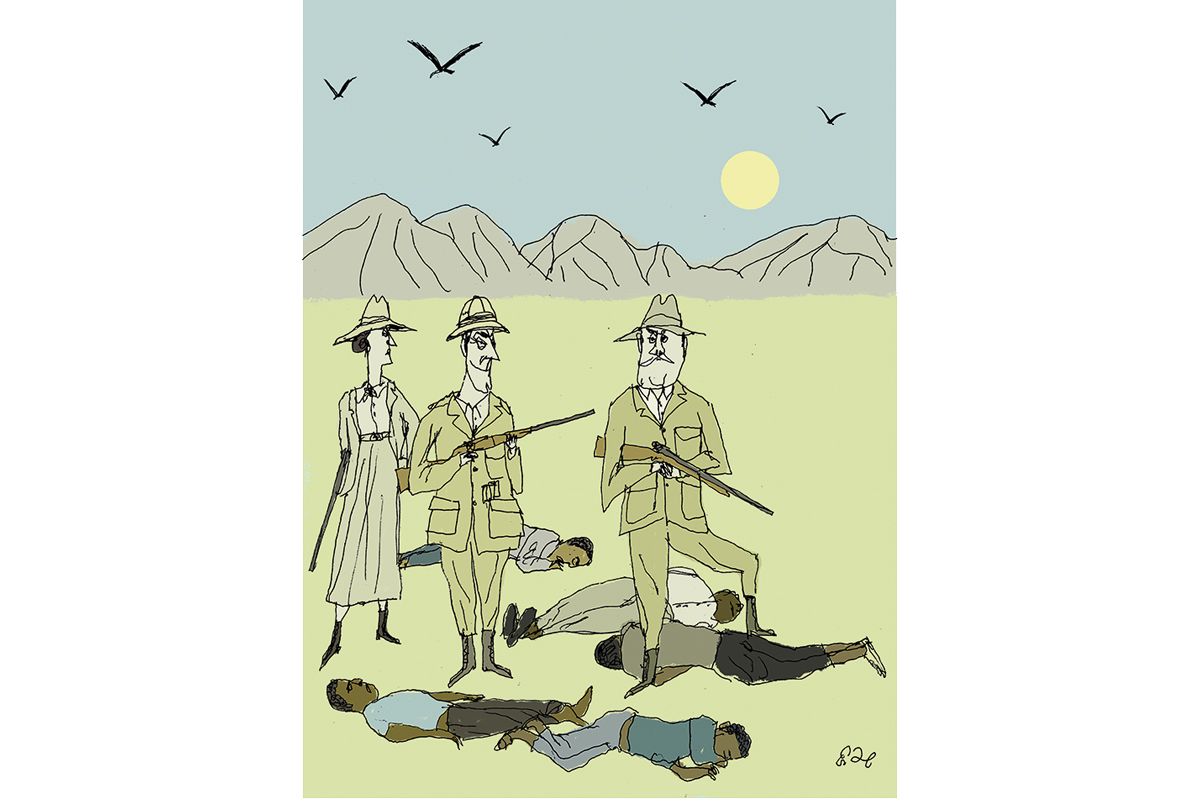

The security vacuum in Syria is an ideal environment for the return of Sunni jihadis

The fall of Baghouz brought to a close the five-year period in which Islamic State presided over a de facto sovereign area. It did not, however, mean the end of ISIS as an organization. It retained its leadership structure, its hardcore militants and supporters, and access to both weaponry and money. In subsequent years, it has been sporadically active in its heartland and birthplace, Iraq, in Syria and further afield. There are now indications that its activities are once more on the rise.

The revival of ISIS preceded the sudden fall of the Assad regime in December last year. In the course of that year, attacks by the organization tripled in comparison to 2023. But a number of factors have emerged since the old regime’s fall which are serving to exacerbate the situation.

Firstly, the security vacuum in much of Syria is an ideal environment for the return of the Sunni jihadis. A few days after my conversation with Ilham Ahmed, I drove with a colleague across the Badiya desert, which she had cited as the main area of ISIS activity. The Badiya is a large desert area in Syria’s center.

We were on the way from the SDF-controlled area of Syria east of the Euphrates to the capital, Damascus. To get there, we crossed the Euphrates at Tabqa and shortly afterwards passed through the final checkpoint of the SDF. The distance from Tabqa to Homs is 225 kilometers. From the last SDF checkpoint until just a few kilometers from Homs, we encountered not a single position or checkpoint of the new Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) regime.

This is the security vacuum to which Ilham Ahmed was referring. The immediate danger resulting from it is that of robbery. Certain Beduin clans are known for their practice of swooping down on lone cars on the highway. But the empty desert also forms an ideal environment for the jihadis, whose relations with certain members of the Beduin in turn enable them to stay in the area and cross it safely. HTS, it is worth remembering, was an organization of around 40,000 members at the time that it took power in Damascus. The new authorities disbanded Assad’s police and security forces and are currently in the process of creating their own. In the meantime, ISIS is able to organize undisturbed in the vacuum.

The second matter of concern which Ilham Ahmed raised was that of ISIS prisoners and their families. In this regard, it should be noted that while HTS at times challenged ISIS and associated groups, it also emerges from the same ideological and organizational roots. In April 2024 I visited the al-Hol camp, which houses 37,000 family members of ISIS fighters. At that time, a senior official at the camp told me that the most common target destination for residents escaping the camp was the HTS-controlled enclave in Idlib. There have been cases where ISIS families escaping al-Hol took enslaved Yazidis with them, secure in the knowledge that in the HTS area, this arrangement could continue undisturbed.

Now, of course, the HTS area of control, at least nominally, comprises the entirety of Syria. Visiting the teeming al-Hol camp again in January, I was told by a senior official there that tensions rose in the camp in the days following Assad’s fall, with residents declaring Syria to be “liberated” and anticipating their own imminent freeing at the hands of HTS. In subsequent days, residents began to tell staff members “it’s close,” (“Qariban” in Arabic), referring to their belief in their imminent liberation.

As of now, the new HTS government is demanding that the SDF hand over administration of the camps to the Damascus authorities. This does not appear immediately imminent. But all indications are that the Trump administration plans to withdraw the 2,000 US service personnel currently located in the Kurdish-controlled area in the not too distant future. If these forces are withdrawn, the SDF is likely to have little choice but to negotiate its own demise with the authorities in Damascus. The prospect will then arise of ISIS prisoners being guarded by their close ideological compatriots in HTS, which was until 2016 the official franchise of al-Qaeda in Syria. The disturbing implications of this are plain.

The first iteration of ISIS was able to emerge and grow because of weak governance and instability in Iraq, and chaos in Syria. As of now, the group is reorganizing and measurably increasing activities in post-Assad Syria. It would be a mistake for the West to ignore this, or to assume that if allowed to continue unchecked it will remain confined to inside Syria’s borders.

Leave a Reply