To see the catastrophic effect TikTok has on the brains of our young, you don’t have to look very far. Earlier this year a young family member ended up in the emergency room with a cup vacuum-stuck to her lips. After a few tugs and half a jar of Vaseline, it turned out that the bright idea stemmed from the #KylieJennerChallenge on TikTok.

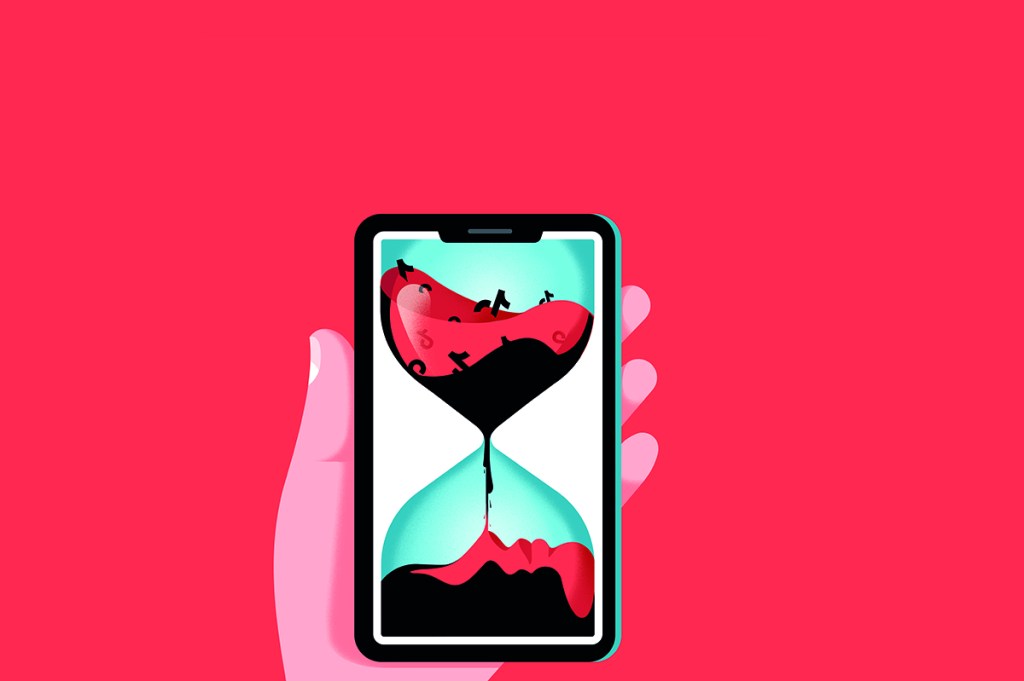

A few thick lips aside, there is something sinister going on with the Chinese-run platform. With every iteration of social media, the corresponding brood of teens has become lonelier, more miserable and even more anxious. This process has reached its purest form in TikTok. The difference is that this time it might have been by design.

“Beijing’s digital fentanyl” is how the Federal Communications Commission’s Brendan Carr describes the app. “The problems present themselves as soon as you sign up; it starts feeding you content directly from a Beijing-originated algorithm.” Mr. Carr is one of many Americans calling for a total ban on TikTok. One reason, he says, was a recent study showing that accounts set up for thirteen-year-old girls were offering self-harm and eating-disorder content in as little as three minutes.

Is this all that different from my teenage years, when eating disorders and self-harm were rife among youngsters with the help of a different social media website, Tumblr? Anyone who was a teenage girl in the aughts will tell you of the streams of Tumblr pictures, the artily lit goths with nihilistic phrases carved into their arms.

While Twitter and Instagram offer you the choice of which accounts to follow, TikTok gives users very little control over what they see. As you flick through its videos, the app measures your dwell time, whether you look at the comments or click on the author’s profile. All these things tell TikTok whether you’re engaged, and whether or not you’re interested in this content. The problem, of course, is that you might be one of those young women recovering from an eating disorder. On one level, you want to avoid content about bulimia or anorexia. But on another, you can’t help looking, even if for a moment. TikTok measures all this and force-feeds you your instinctive desires. Conscious choice is almost entirely cut out.

It isn’t just kids. I often find myself having a TikTok break. Horizontal in bed, I promise myself I’ll look at the app “just for ten minutes.” Hours later I catch myself still there, with no recollection of where the day has gone. By design, TikTok shows series of very short, emotionally engaging clips. You might see a soldier coming home from duty, hugging his kids, followed by a crackhead screaming in her car, followed by a video recipe for apple pie, followed by dogs, road traffic accidents, cottage-core inspo, street pranks, dancing teenagers and bar fights. Each time emotions are elicited, only to be immediately forgotten once the next video hits. When you finally manage to put your phone down, there’s a strange feeling of emptiness. Your emotions are all jumbled up for no good reason, no narrative to explain why you feel as you do. After all, you’ve just watched a hundred-plus videos with nothing linking them together, apart from the fact that a Chinese-designed algorithm thought they might interest you.

As of last November, TikTok had over 138 million active users in the US, two-thirds of whom are under thirty. Dr. David Barnhart, clinical mental health counselor at Behavioral Sciences of Alabama, has previously spoken about how TikTok distorts the way people view themselves. He has warned that the effect of viewing dozens of videos within minutes activates reward pathways in the brain. The result in young users is a reaction that looks a lot like addiction, with users seeking constant stimulation. “They begin to get this view of themselves in comparison to other people. The more of that we see, the more distorted our view of what it’s like to be the best, to be good,” Barnhart says. “We don’t have an awareness of what we are doing to our own brains.”

But Dr. Barnhart argues that regulating usage, rather than banning the app altogether, is the solution. “Contingency management,” he says, such as parents setting restrictions on app usage and making sure children get their daily tasks done before using it, could lessen the damage. I’m not sure I agree. Even an hour a day can result in a trip to the emergency room, as I know all too well.

Then there’s the issue of national security. ByteDance, the Chinese company that developed TikTok, has an internal CCP committee as part of its governance structure, headed by the company’s vice president. In 2021, the Chinese government took a stake in the firm and secured a seat on the three-person board. Brendan Carr’s main concern is that the data that TikTok collects flows back to Beijing. “For years, TikTok officials told US regulators not to worry. They told us all our data is stored outside of China, and in some cases, they went so far as to have one of their officials say the data doesn’t even exist in China.” Now we know that isn’t true. Last summer, BuzzFeed got hold of internal TikTok communications that proved everything on the app, from everyone on the app, is seen in Beijing.

In December, ByteDance admitted to using TikTok to track foreign journalists. The company’s chief internal auditor led a team that looked at journalists’ IP addresses to try to work out whether they were in the same location as staff suspected of leaking. The company had initially denied the allegations when first reported, saying they could not “monitor US users in the article suggested.” Four members of staff were subsequently fired, including the chief auditor.

Why should people like me care? I’m not interesting enough for China to want to spy on. But the dance videos, or cooking clips, or that snap of the really cute cockapoo are just the sheep’s clothing. What is really being collected in China — which we are told in the Terms of Service — is our search and browsing history, our keystroke patterns. The ToS even tell us that the app reserves the right to get our biometrics, including face prints and voiceprints.

Over the last year at least seven Republican governors have taken steps to ban TikTok from government devices amid spyware concerns. In December, Congress voted for the same rule at a federal level. The Biden administration has been criticized for a drawn-out review of whether the Chinese-owned app should be restricted. Wisconsin representative Mike Gallagher (interviewed on p.26), chair of the House select committee on China, says that “allowing the app to continue to operate in the US would be like allowing the USSR to buy up the New York Times, Washington Post and major broadcast networks during the Cold War.”

The irony is that in China, TikTok provides users with a more optimistic outlook and encourages users to become moral citizens in the eyes of the CCP. Douyin, which is what TikTok is called in China, is a hit even with parents. Despite efforts of its parent company ByteDance to present Douyin and TikTok as the same product, they are actually two separate entities. In China, if you are under fourteen, your Douyin use is capped at forty minutes a day. It also feeds you different content, with education at the forefront. Art, science, architecture and pro-CCP content are also pushed. In a recent 60 Minutes report, Tristan Harris, co-founder of the Center for Humane Technology, compares the Chinese version to “spinach” and its exported, Western version to “opium.”

Fox News anchor Tucker Carlson recently compared TikTok and Douyin. The Chinese version shows grinning graduates collecting their diplomas and young people helping the elderly. The “international” version of TikTok, which is what American children are watching, is flooded with twerking, info about gender-altering therapies, even lessons for children on how to hide their “gender identity” from their parents. Last year the Daily Mail alleged that TikTok was promoting gender change surgery as something “cool.” By the time that report was published, such videos had been watched over 26 billion times. A few years ago it would have seemed paranoid to claim TikTok was designed to corrupt young minds; now it is happening before our eyes.

On an average day, a TikTok user spends ninety-five minutes on the app. This is considerably more time than averages on other popular social media platforms such as Instagram (twenty-nine minutes) and Snapchat (twenty-eight minutes). For those of us with TikTok Brain, our attention span has been smashed to smithereens. Short-term memory and ability to concentrate have been affected: devoted TikTokers report that they are unable to focus on longer video formats and 50 percent of users admit that they find longer videos “stressful.” Now, where was I?

Apparently binging on fifteen- to-thirty-second clips has ruined our ability to focus. The most tragic part of all this is that we are watching this affect our children day-to-day. I asked Carr what the next generation of Americans will look like if TikTok carries on as is. He told me of a report that talked about the career aspirations of youth. Young people in China, asked what they wanted to be, said an astronaut. When the same study asked American children, they said they wanted to be “influencers.” Do we really want two-thirds of America’s youth listening to Beijing’s propaganda for ninety-plus minutes every day? I don’t think so. But then again, I’m not even sure what I think anymore.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s February 2023 World edition.