Vilnius, Lithuania

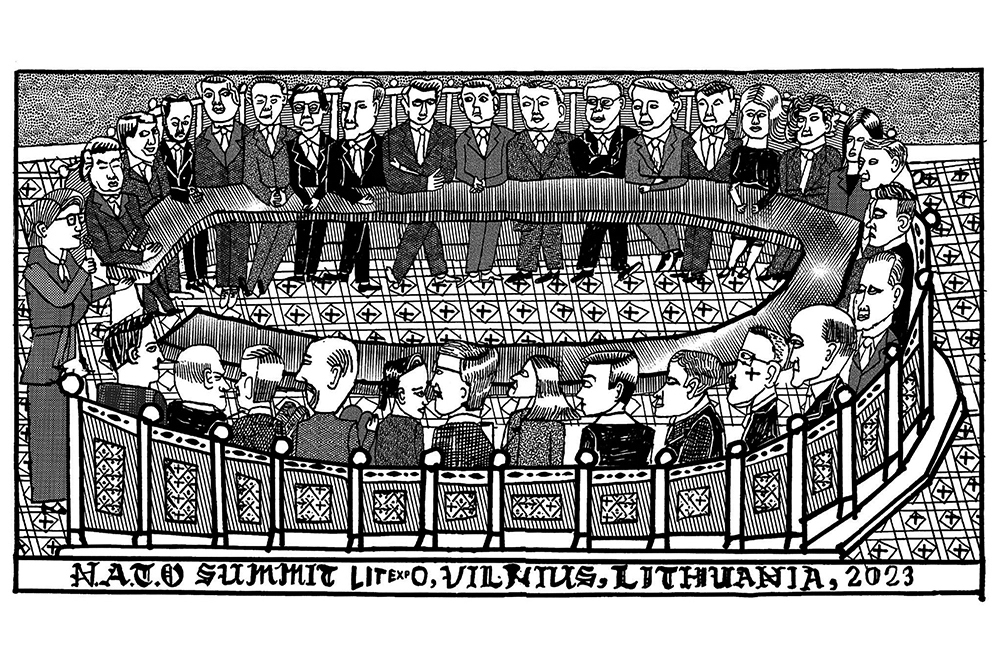

In July, Lithuania’s Prime Minister Ingrida Simonyte will welcome NATO leaders to Vilnius for one of the most important summits in the alliance’s history. Top of the agenda will be how to help Ukraine push back Vladimir Putin’s forces. But a more thorny problem will be whether to formally offer membership to Kyiv — a move that would make Ukraine’s front lines NATO’s own.

Simonyte believes that the war could have been avoided if NATO had accepted Ukraine and Georgia’s membership bids back in 2008. Before Putin invaded Ukraine last year, she says, “western leaders and western organizations were ready to abandon their positions every time Russia was pressing.” Indeed it was only at the Madrid NATO summit last year that Russia was formally declared “a threat rather than just a rival.” The Baltic countries were under no such illusions about Russia’s hostile intent. The Ukraine invasion was being “prepared for many, many years,” says Simonyte. For Putin, “building prosperity, trying to increase people’s welfare is a little bit tiresome… it’s easier to give people a substitute for progress, for instance the greatness of your nation.” And for Russia, now as historically, greatness is defined not in terms of “scientific achievements or economic achievements but by controlling people around you. That was the concept of Russian empire and is still the concept of Russian elite, unfortunately.”

Putin ‘did everything for his neighbors to feel insecure and of course look for security guarantees’

Simonyte strongly rejects suggestions that there was anything the West or Volodymyr Zelensky could have done differently in order to avert war. “The usual Putin story is that it was NATO that was moving eastward, pressing Russia from the west. But this is nonsense because there was no real presence whatsoever of NATO [forces in the Baltic] until he grabbed Crimea,” she says. “We were members of NATO, yes. But the debate about any deployment in the region was very complicated… only after [2014] was there any enhanced forward presence established in the Baltic states.’ On the contrary, she argues, it was Putin who “did everything for his neighbors to feel insecure and of course look for security guarantees. And that’s NATO.”

Lithuania was sending military aid to Ukraine long before most of its NATO allies were. But as Ukraine prepares for a major counter-offensive that is likely to define the endgame of the war, what will victory look like? Simonyte’s vision tallies exactly with Zelensky’s: “Russia is expelled from all [Ukraine’s] territory, justice for the guilty is implemented, and the rebuilding of the country is financed by those who are guilty of that devastation.” And if none of those things happen? “Then there will be no peace in Europe.”

But some NATO leaders — and increasing numbers of European voters — are wary of open-ended support for a war that Zelensky last week warned could last for “decades.” Recent polls in Italy, for instance, suggest that just a third of voters agree with continuing arms supplies to Ukraine. So far, Simonyte insists, NATO support for Ukraine is “as strong as it was a year ago, I have no doubt.” Nonetheless, she acknowledges that there are “debates” in many countries between advocates of peace — which would come at the expense of territorial losses for Ukraine — versus full justice. “Some of the people are saying we are tired of this war — well, yeah, nobody said that would be pleasant. But if [Russia] is not defeated then it will just be a matter of time before it regroups, re-arms, and that it will come for somebody next.” Is there any scenario short of fully expelling Russia from all Ukraine — including Crimea — that could also count as victory? That’s up to Ukraine to decide, says Simonyte — but she sees “very little probability that Ukraine would cede lands for any kind of peace deal.” As for future relations with a post-war Russia, Simonyte sees some hope that in the Russian government there are “practical people who do understand that this [war] makes no sense” — but they’re not “within the circle of decision making.”

Simonyte sees no problem with Ukraine’s apparent attacks against oil storage bases and freight trains inside Russia — and even a drone strike on the Kremlin’s Senate Palace. “Russia is at war, though I know that they pretend they are not at war,” she says. “I think it’s a big mistake to think that if you’re at war with another country, then the war is only in that other country for some reason. And you have parades, festivals, people in cafés, and everything continues as normal. Life is not normal.”

‘It’s a big mistake to think that if you’re at war with another country, then the war is only in that country’

Does she believe that September’s destruction of the four Nord Stream gas pipelines that run past Lithuania’s coast was done by Ukrainian freelancers, as recent reports have suggested? “If you ask me who would benefit [from the destruction of Nord Stream] I would say it’s the Russians,” she says. “They can claim force majeure in arbitration cases for not delivering gas to European countries because there are still contracts that are binding… But I’m not in intelligence. So I will wait until there is some formal investigation and formal conclusions.”

A former economics professor, veteran minister and parliamentarian, forty-eight-year-old Simonyte has led her 2.8 million-strong country since 2020. There’s no real difference in the way that men and women lead, she says — “I think it’s always about the personality rather than the sex.” But some voters see female leaders as “a mom in the family… which is maybe why during a crisis, you quite often see a woman being elected.”

The three years of Simonyte’s premiership have seen a fair share of crises — Covid, unrest in neighboring Belarus that followed a presidential election that was widely regarded as stolen, and the invasion of Ukraine. Simonyte offered the exiled Belarusian opposition leader Svetlana Tikhanovskaya not only political asylum in Vilnius but official recognition as the government of Belarus in exile. When up to a million Russians fled from political repression and mobilization, several thousand found a home in Lithuania — alongside a much larger number of Ukrainians.

In neighboring Latvia and Estonia, Russians represent a quarter of the population — some of whom complain that strict language aptitude laws have relegated them to the status of second-class citizens. Latvian authorities last year controversially shut down the Dozhd TV Russian-language television station and withdrew residence permits for his émigré staff on the dubious grounds that the staunchly opposition-minded channel supported the Russian army.

Lithuania has so far been relatively free of these culture wars, in part because just 7 percent of Lithuanian citizens are ethnic Russians. “About 10 percent of our population would say that [Lithuania] was better under the Soviets than it is in an independent state,” she says. “But I lived under that regime for fifteen years and I know that this is a completely fake idea.” Russians in Lithuania are in no way second-class citizens, she insists: like Poles, Belarusians and Jews they have their own native-language schools. And she says that her country will continue to issue humanitarian visas to Belarusian and Russian activists. “Can I say that all of them are like leaders and beacons of democratic transition? Not necessarily… but we are ready to take this risk.”

One overseas culture war that has had a direct impact on Lithuania has been Brexit. Before Britain left the EU, hundreds of thousands of educated young Lithuanians left the country for jobs in more prosperous parts of Europe — with many ending up in London. Brexit and Covid brought many back home — which is good news for the Lithuanian economy. “I feel pity for Britain for leaving the European Union,” she says. “But on a bilateral level, I think we still have perfect relations and a good understanding of the global situation.” Europe has become stronger after Britain’s exit, she argues, thanks to the collective challenge of Covid and the Ukraine war. “Before, it was more an economic than a geopolitical player,” she says. But now, “the EU has a stronger geo-political stance than it ever had.”

Simonyte hasn’t met Putin personally — “not something that I miss very much” — and, since the International Criminal Court issued its war crimes warrant against him, is now unlikely to. But in a few weeks she will be hosting allies from across the western world who have come to realize that the Baltics, with their repeatedly ignored warnings of the dangers posed by Russia, are perhaps worth listening to.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.