I was twenty-one in 1960 and I can remember exactly what my godfather gave me for my coming-of-age present. It was an abortion. He didn’t know this, of course, but he gave me £200 and that is what I used it for.

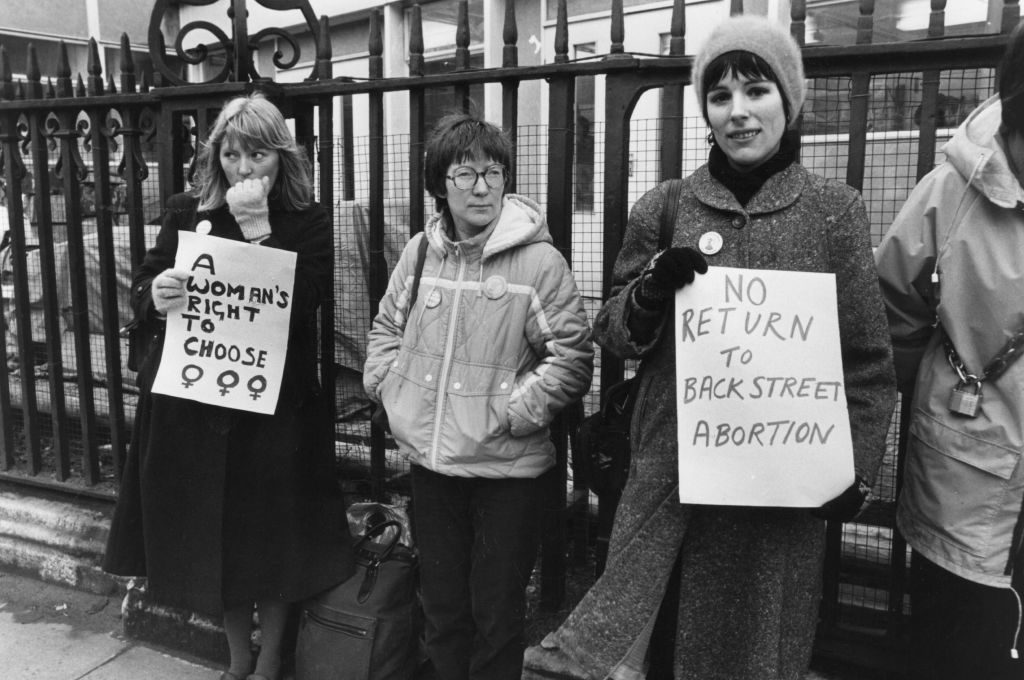

I have never told this story before and am only doing so now because of the return of abortion to the heart of political debate after last year’s Dobbs decision, which has led to the tightening of abortion laws in many states across America. I know firsthand about the danger and misery of illegal abortions, because I had one myself in the days, pre-1967, when abortion was illegal in Britain. The nightmare that has been every young woman’s dread since history began — the thing that we never stopped worrying about in the Sixties with our rather primitive methods of birth control — had happened to me. My period was late. The thought consumed my life. What would I do? I jumped up and down, ran, walked, drank gin, touched my toes a hundred times — all to bring on the period. Nothing happened.

In 1960 having an “illegitimate” baby brought shame on your family. In our village everyone knew and gossiped about the local “unmarried mother.” The only thing I was absolutely certain of was that I could not bring this shame on my good, loving Catholic parents. I would rather die. I had to have an abortion. My boyfriend (my first, and I didn’t want to marry him) was in the army and posted abroad, so I faced this alone.

The only way you could have a legal abortion before 1968 was if you could prove that having a baby would cause you physical or mental problems. Somehow (I don’t remember how) I saw a psychiatrist whom I had to convince of this, but I couldn’t. He referred me to a Catholic adoption agency where they tried to convince me to have the baby and give it up for adoption. I didn’t consider this for a second. But what was the alternative?

The days were speeding past. Soon it would be too late. I was desperate but didn’t know what to do. Panicked, I confided in a friend at the office. The next day she brought over another colleague who had had an abortion a few months earlier. Speaking in whispers in the ladies loo, she told me it had been done by a gynecologist who had been struck off the medical register for drunkenness, and was practicing illegally, operating in his flat in a big apartment block off the Marble Arch at the end of Oxford Street. My office friend said I could stay with her for a couple of days after the procedure. I told my own flatmate that I was feeding her cat while she was away on a short holiday.

I rang the struck-off doctor; the appointment was made, I got the money in cash, and I went alone to the rendezvous because secrecy was all important — apart from anything else I was now complicit in something illegal.

The “doctor,” middle-aged, big and red-faced with slightly bloodshot eyes, let me into his apartment. He told me to have a bath. I hadn’t expected this, but I was so consumed by fear, so ashamed and so shy that I just did whatever he told me to do.

I took off my clothes; he ran the bath and sat on the edge watching me as I got in and soaped myself. He was clearly amused to see the collection of holy medals I was wearing round my neck to protect myself from evil. I couldn’t bear to look at him.

He gave me a cotton wrap and led me to a bedroom with a double bed and made me lie across the bed with my legs over the side. “I bet you like sex on the edge of the bed,” he said. I didn’t respond, I was dizzy with terror, praying under my breath.

He didn’t look like a doctor about to do an operation: he was in shirt and trousers. Then he put some kind of mask over my mouth and nose and told me to breathe and I lost consciousness.

When I came to, I felt sick. I have no idea how long afterward I opened my eyes and saw that he was in his underpants. I closed them again, not wanting him to notice that I had noticed.

I got dressed and left as quickly as I could. He — fully dressed by then — didn’t try to delay me. I can’t remember if he called a taxi or whether I found one, but I got to my colleague’s and rested up for a couple of days. I couldn’t bear to think of what he could have done to me while I was asleep. I felt dirty, ashamed, guilty and wretched (I still can’t bear to think about it) but I was no longer pregnant. My life proceeded in a totally different way to how it would have done had I married a young army officer at the age of twenty-one.

A couple of months after my ordeal my office friend took me aside and whispered that the “doctor” had just botched an operation and killed a young woman. He was sent to prison for manslaughter.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s August 2023 World edition.