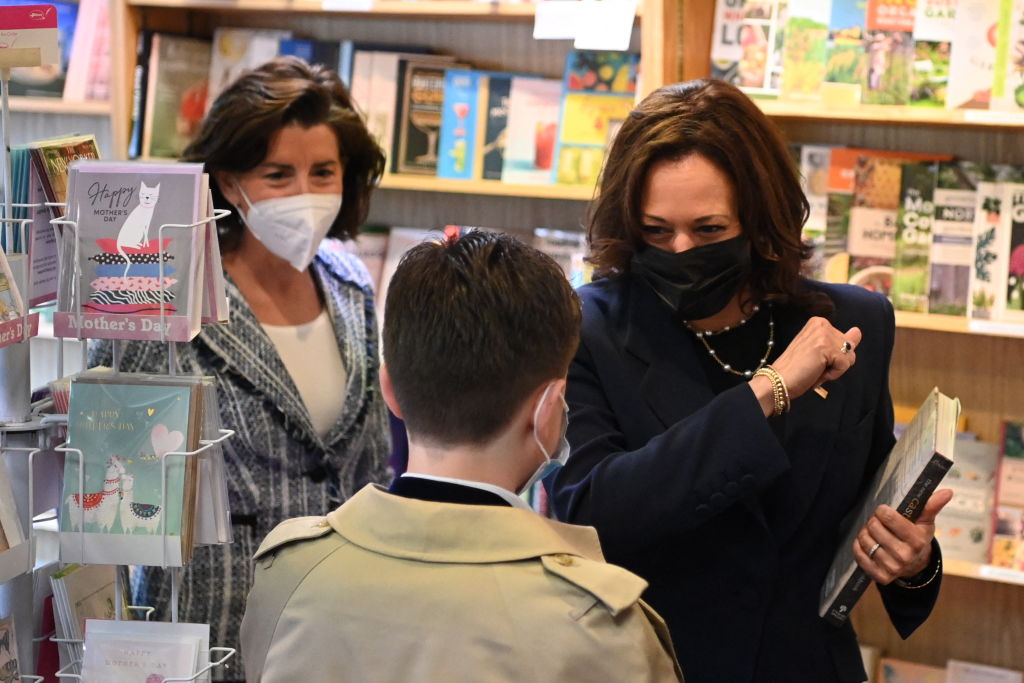

Here’s a treat for teenagers; there’s a version of Kamala Harris’s The Truths We Hold: Young Readers’ Edition in a bookshop near you. It’s one for the same section as Michelle Obama’s Becoming: Adapted for Young Readers, except with next to nothing about boys and first kisses.

However, to show willing, our author gives us a little anecdote from the party for her becoming a senator for California, a result that coincided with the election of you know who. Her godson, Alexander, 9, came up to her with tears welling in his eyes. ‘“Come here, little man, what’s wrong?” Alexander looked up…his voice was trembling. “Auntie Kamala, that man can’t win. He’s not going to win, is he?” Alexander’s worry broke my heart… His father, Reggie, took him outside to try to console him. “Alexander, you know that sometimes superheroes are facing a big challenge because a villain is coming for them? What do they do when that happens?” “They fight back”, he whimpered. “That’s right. They fight back with emotion…and that’s what we’re going to do.”’ You know, I think little Alexander and the child readers may end up with a view of politics that’s a teensy bit Manichean.

Political memoirs amended for younger readers are, of course, fine and dandy and Kamala is nothing if not upfront about where she’s coming from. But they’re part of a bigger pictures whereby children’s books are now overtly or subliminally designed to inculcate a set of approved values in child readers. And the value-promotion goes beyond party politics to issues of race and sexuality. In this very loaded worldview, the one thing that gets lost is the crucial, possibly the only, question relevant to children’s books: whether they are worth reading and looking at and whether they engage the reader…pretty well the same criterion for most reading, really, except that for children, stories and pictures really matter.

Recently, the American Library Association announced its 2021 Rainbow Reading list, with 129 librarian-approved, LGBTQ-inclusive children’s and young adult books — up from fewer than 50 in 2008. The list was drawn from the ALA’s Rainbow Round Table longlist of 600 books, from board books to biographies. The committee noted, ‘We provide you with titles that incorporate the wide and varied lives of young people, non-fiction titles that challenge the status quo, and fiction that will break your heart and mend it together again.’

So, the imprimatur of the oldest and most established library association in the world is being given to books on the basis of representing a particular kind of identity and establishing an approved take on that identity.

I get quite a few books that promote a LGBTQ outlook as a reviewer: the latest features ‘Josh’, who ‘can’t wait until he’s 18, the legal age when he can finally contact his donor — he’ll do anything to find out who he is’. Another chirpy book with doodles features a girl whose two moms are going to get married and is amazed to find one of her friends ‘not even knowing that two women or two men could get married until very recently’. But it’s fine because the friend’s mother falls in love with another woman and has to be reminded that ‘not long ago you didn’t know anything about women loving women’. Then there’s All Boys Aren’t Blue, a memoir covering, as the blurb says, ‘topics such as gender identity, toxic masculinity, brotherhood, inequality consent and Black joy’. And what they have in common is that they’re from the big imprints and they are designed to change attitudes. Puffin Books, a Penguin imprint for children, used to have a legendarily brilliant children’s list; now it has an LGBTQ range indicated by a rainbow spine which denotes an agenda. Buying children’s books used to be relatively unproblematic; now children’s sections of the bookshops are dotted with areas denoting identity interests.

Chief of these is race, and for the diversity brigade, the main issue is that the book is written from a non-white perspective about non-white characters. It’s a reductionist take on children’s literature. The movement for greater diversity was given initial impetus back in 2014 when the black author, Walter Dean Myers and his son, the author and illustrator Christopher Myers, wrote in the New York Times asking ‘Where are the people of color in children’s books?’ In the same year, Ellen Oh launched the association We Need Diverse Books, to promote non-white representation through grants and links with publishers. And the effort worked…it’s driving up the diversity quota.

The Associated Press reported figures from the Co-operative Children’s Book Center, an organization that monitors diversity in children’s books, which showed that books written by non-white authors in 2020 increased by three percent in a year to 26.8 percent of the total, while children’s books written about non-white characters or subjects grew to 30 percent. But are those books worth reading? It’s the one question worth asking.

When it comes to consciousness raising you can never start too early: one board book for infants in the bookshop near me has the engaging title: Antiracist Baby. The cover shows a little girl depicted, like an infant Kamala lisping ‘Fweedom’, at a rally, strapped to her father’s chest. Lesson 1 is ‘open your eyes to all skin colors…if you claim to be colorblind you close your eyes to what’s right in front of you.’ Oh please. It’s a baby book.

I can, of course, see that children may like to see characters who look and sound like them, though I never myself felt alienated by the fantastical Moomins or by class (a more important issue) when it came to boarding school stories or by boy heroes in the books I liked. If the story’s good, you identify with the character…end of. But that’s not what the move to diversity is about; it’s driven by something approaching a quota system for non-white representation in children’s books whereby diversity is a good in itself, independent of whether the books are brilliant.

There are authors like Jason Reynolds whose latest, with Brendan Kiely, called all american boys [sic] is about police violence against black youth, who writes from a black perspective, but the human drama is engaging even if you don’t have similar personal experience or can’t identify ethnically with the characters. And that is kind of what fiction does.

Once the children’s section of a bookshop was where you sought reading for pleasure; now children’s books are loaded with baggage to do with a cultural agenda that readers and their parents may not even be aware of. Is it going to make children more likely to devour books, to develop that appetite for reading that will always stay with them? I doubt it.