There’s a school of thought that says the events in Washington, DC on January 6, 2021 were the great communal wound of Western democracy, an outrage seen around the world when a retired cowboy dared put his boots up on an aide to the speaker of the House’s desk (he later got four-and-a-half years for his trouble), and the commander-in-chief tried to grab the steering wheel from a Secret Service agent to turn his SUV around in the direction of the mob so he could join them.

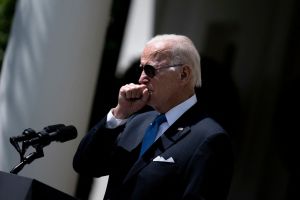

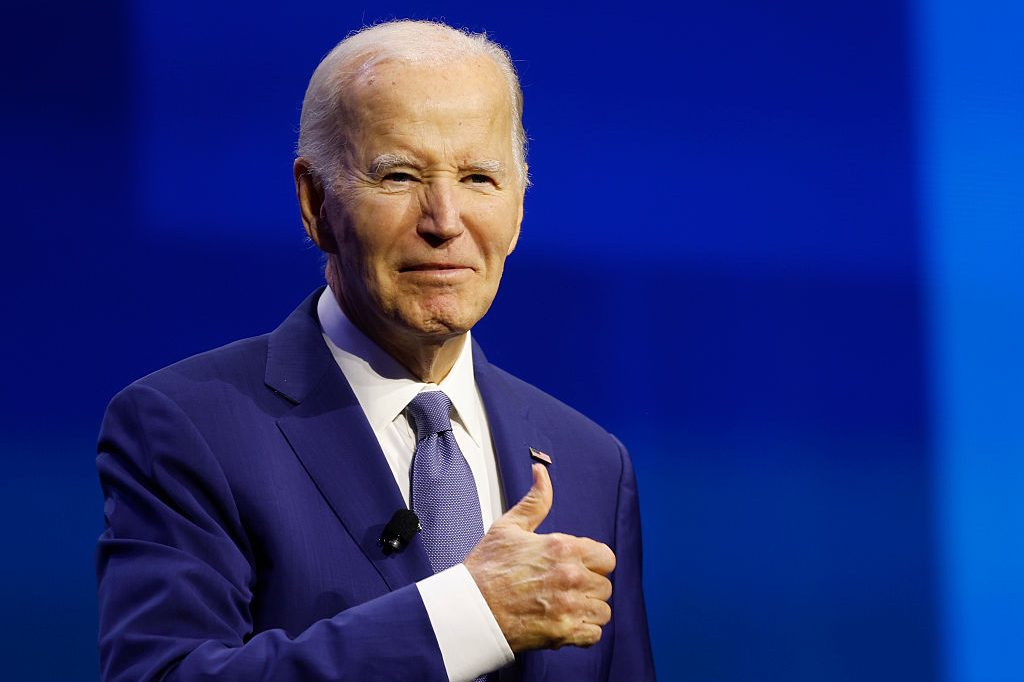

“I did not seek the fight brought to this Capitol, but I will not shrink from it either,” President Biden announced through clenched teeth in a speech delivered just outside the House chamber a year later. “I will stand in this breach. I will defend this nation. And I will allow no one to place a dagger at the throat of democracy.”

It’s good to know that Biden stands ready at a moment’s notice to intervene on our behalf to save the Republic from itself. But what would he have made of the equally potent events that took place a hundred years ago, in the course of a dark night in Munich?

To set the scene, we need to rewind to 1919, and the first of what proved to be several miscalculations on the part of the established political class that helped bring the Nazi party to power. In October of that year, the Propaganda Office of the Bavarian Defense Department ordered a thirty-year-old World War One veteran named Adolf Hitler to infiltrate the far-right German Workers’ Party and report back on their activities. Hitler did as he was told, but instead of denouncing the GWP, he found that he was drawn to much of their manifesto, notably their belief that Germany had lost the war not on the battlefield, but as a result of being “stabbed in the back” by its own government in league with “Jews, Marxists and other criminal swine.”

By late 1923, Hitler’s conviction on this point had grown to encourage thoughts of taking direct action against the Weimar Republic. After enlisting the help of the wartime leader General Erich Ludendorff, and trailed by some 600 storm troopers, he set out on the night of November 8 for Munich’s cavernous Bürgerbräukeller, where the national uprising was to begin. Anyone familiar with the atmosphere of a modern-day urban rock club need only think of that same setting, but with added noise and smoke, and a clientele dressed largely in Lederhosen, to get some of the flavor.

Finding himself on the premises ahead of his supporters, Hitler, dressed for the occasion in a long black trench coat and carrying a dog whip, sat down at the bar and ordered two steins of beer at the going rate of a million marks each. After a few minutes, a unit of helmeted storm troopers burst through the door and set up a heavy machine-gun facing the crowd. At that, Hitler put down his beer, removing his trench coat to reveal a black-tailed morning coat with a swastika armband, stood on a chair and began to speak. Unable to make himself heard amid the uproar, he shouted “Quiet!”, took out his Browning pistol and fired a shot into the ceiling.

“The revolution has begun,” Hitler announced.

Having successfully got his audience’s attention, Hitler strode to a platform at the end of the room, accompanied by his cohorts Rudolf Hess and Hermann Göring, slowly looked the crowd up and down, and said: “You may be assured that what motivates me is neither self-conceit nor self-interest, but only a burning desire to join battle in this grave hour for our Fatherland…. One thing I can tell you: either the German revolution begins tonight, or we will all be dead by dawn!”

It was a typically stirring speech, but alas for Hitler and the others it also represented the high watermark of the putsch, which from then on displayed all the finesse of a Fawlty Towers fire drill. Hearing that some of his troops were bogged down elsewhere in the city, Hitler decided to go to their assistance. “I am leaving,” he announced, even in the act of struggling back into his trench coat, “to fulfill the vow I made to myself five years ago to know neither rest nor peace until out of the ruins of a broken Germany there should arise once more a nation of power and greatness, of freedom and splendor” — nobody ever accused him of understatement — and the whole endeavor quickly collapsed in his absence. The hundreds of customers who remained in the Bürgerbräukeller began chatting and drinking again, and no one in Hitler’s entourage did anything useful in terms of seizing local radio stations or government offices. Something like a party atmosphere seems to have ensued in the beerhall, and a large bill for the night’s entertainment was eventually presented to the Nazi Party for payment.

At ten the next freezing cold morning, Hitler and Ludendorff regrouped at the head of 2,000 supporters to march through the city center. By all accounts it was a somewhat motley parade, with some of the men wearing military uniform and others in work clothes or business suits, while a few tried to keep up their spirits by singing traditional German anthems. When a police cordon confronted them, the ranks broke. Shots rang out, and in the ensuing melée sixteen marchers, four policemen and one unlucky bystander were killed. Hitler himself ran for it, falling and dislocating his shoulder in the process and eventually made his way to a supporter’s home in the nearby town of Uffing, where the police found him two days later. At the time of his arrest, Hitler was dressed in a woman’s fluffy white nightgown, his injured arm in a sling and reportedly threatening to kill himself.

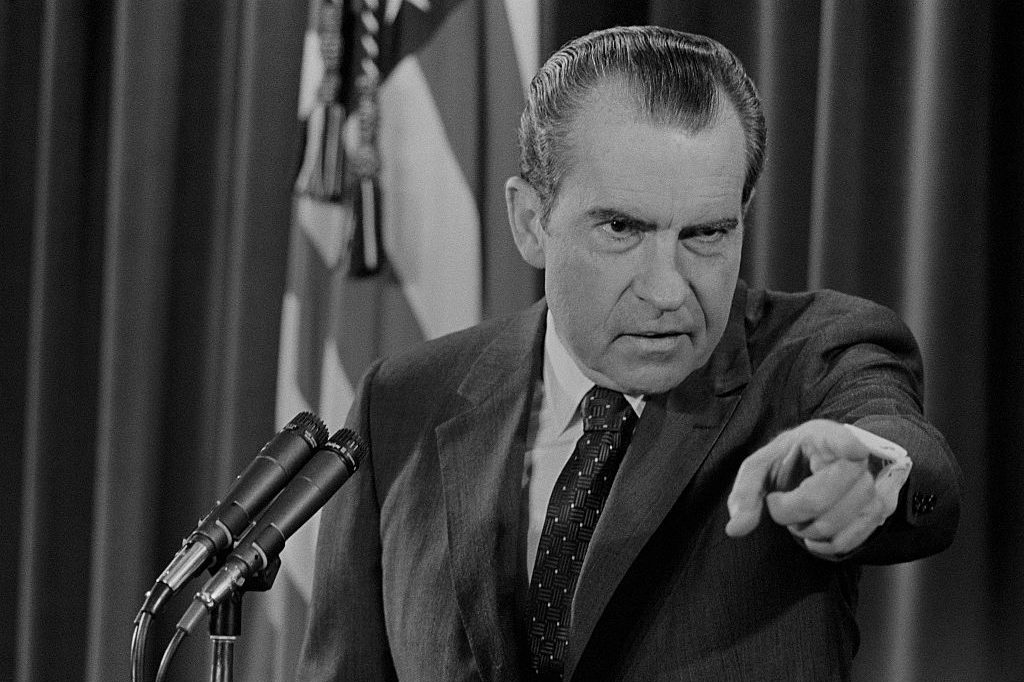

The authorities then made another error by putting Hitler on trial rather than merely sending him into longterm exile. He not only admitted, but actively embraced, the charge of high treason, in effect putting the “swine” in the dock alongside him and achieving significantly more of his goals than in the attempted putsch. His concluding speech, “I consider myself not a traitor, but a loyal German who wanted the best for his people” was met with loud applause in the courtroom and helped establish the myth of the führer-to-be as a selfless patriot determined to save the nation from the effete ruling elite who had led it to ruin in 1918.

Meanwhile, Hitler was sentenced to five years in a minimum-security prison, although serving only eight months, and used the time to compose his page-turning memoir Mein Kampf. The book was slow out of the gate, but eventually did well enough to make its author a small fortune and saddle him with a large tax debt, which was waived at the time he became chancellor of Germany.

In all, then, a case-study about what can happen when the establishment class overreaches itself, and the target of its wrath consistently displays a flair for propaganda that turns the very fact of his prosecution into a political rallying-cry, in a way that somehow rings a bell today.

Leave a Reply