It seems like ancient history now, but the week before the ill-fated summit in Helsinki President Trump nominated Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court. It was Trump’s second nomination to America’s highest court in as many years and conservatives overwhelmingly cheered his choice.

“I’ve often heard that, other than matters of war and peace, this is the most important decision a President will make,” Trump said in the East Room of the White House. “The Supreme Court is entrusted with the safeguarding of the crown jewel of our Republic, the Constitution of the United States.”

Kavanaugh was picked to replace retiring Justice Anthony Kennedy, a Republican appointee who was nevertheless a swing vote on the Supreme Court. If Kavanaugh is confirmed by the Senate, Trump may succeed where even Ronald Reagan failed: installing a reliably conservative majority on the court that may actually threaten liberal precedents like the Roe v. Wade decision legalizing abortion (Kennedy unexpectedly authored a majority opinion affirming Roe in 1992).

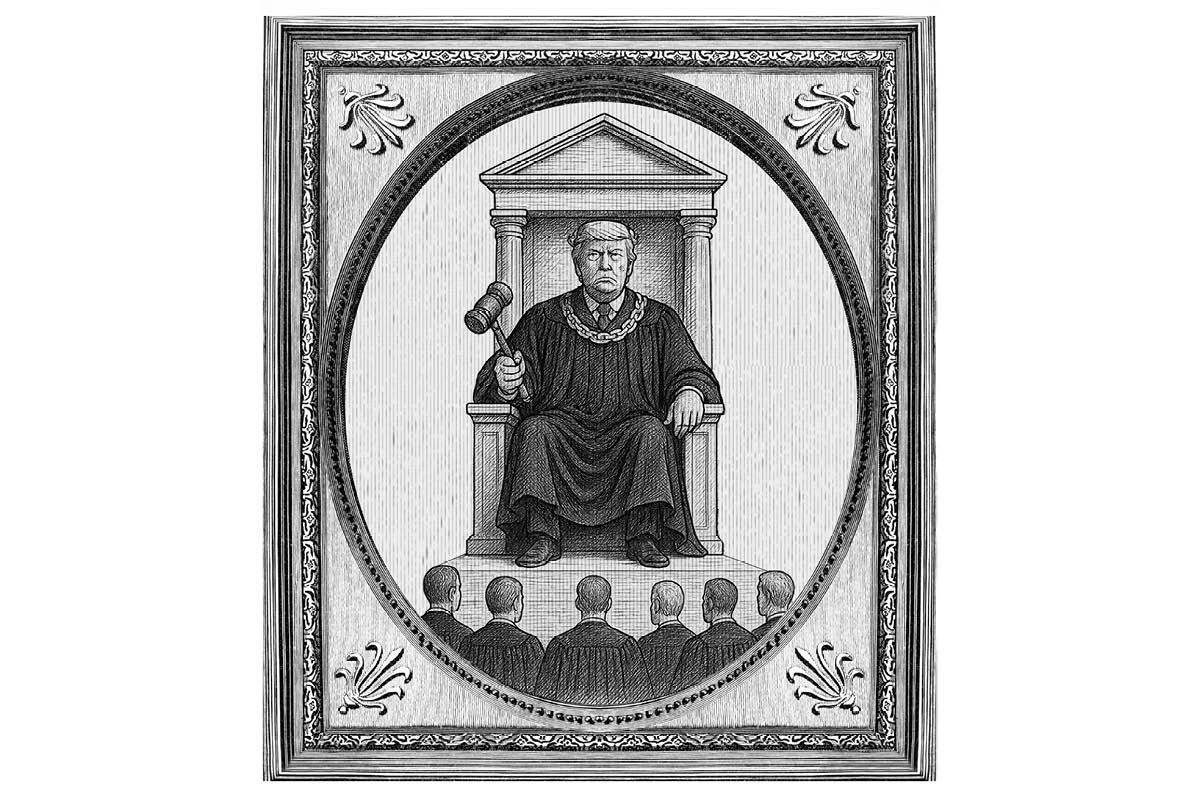

Strikingly, the Supreme Court is just part of Trump’s transformation of the federal judiciary. He has won the approval of the largest number of judges of any president in his first two years in office in recent years. Many of them are young and conservative, meaning their lifetime appointments will reverberate decades after Trump has left the Oval Office.

At this writing, the Senate has confirmed 23 Trump-nominated judges. The effort did hit a speedbump recently when the president was forced to withdraw the nomination of Ryan Bounds to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals after a pair of Republican senators expressed concerns about the nominee’s collegiate writings about race. But that vacancy is likely to be filled eventually.

Trump’s judicial success story is due to several factors. First, Trump came to office with an unusually high number of vacancies. “When I got in, we had over 100 federal judges that weren’t appointed,” the president said during a speech in Ohio earlier this year. “I don’t know why Obama left that. It was like a big, beautiful present to all of us. Why the hell did he leave that?”

Trump went on to call the vacancies “a gift from heaven” and speculated about why Obama left him so many. “Maybe he got complacent,” Trump said of his predecessor. In fact, Republicans took control of the Senate during Obama’s last two years in office and blocked many of his nominees. They kept the late Justice Antonin Scalia’s Supreme Court seat vacant for over a year rather than confirm Obama’s choice of Merrick Garland, allowing Trump to elevate Justice Neil Gorsuch instead.

Second, unlike Obama’s last two years, Trump’s first two years have taken place with his party running the Senate. As long as Trump picks judges Republicans can support, they will reach the bench. While the most conservative are confirmed on straight party-line votes, there are also ten Democratic senators from states Trump won who are up for reelection this year. Some of them occasionally vote with Trump on judges.

Third, Senate rules have changed to make it easier to confirm judges. Under the filibuster, it effectively required 60 votes to end debate and proceed to a vote on the matter at hand. That is still in effect for legislation, but has gradually eroded for presidential appointments. Senate Democrats scrapped the 60-vote threshold for most judicial nominees in 2013 to help Obama get his judges through; Republicans detonated the “nuclear option” to make this apply to the Supreme Court too, so Gorsuch could prevail with a simple majority.

Under the old rules, there is no way Trump could have gotten through so many of his judges—to say nothing of his Cabinet—with a 51-49 Republican Senate majority. This is especially true with one GOP senator, John McCain, convalescing in Arizona and unavailable to vote. Now 50 votes gets it done and there is little Democrats can do about it unless they can persuade some Republicans to vote with them, which bodes well for Kavanaugh.

The most important reason, however, may be that it is now easier for a Republican president to identify and nominate conservative judges than ever before. Trump is benefiting from decades of work done by more ideological people than he who came before him.

Supreme Court justices have in particular been a source of disappointment to conservatives over the years. Some of the most liberal members of the court—Earl Warren, William Brennan, Harry Blackmun, John Paul Stevens and David Souter—were selected by Republican presidents. Other GOP appointees, like Kennedy and Sandra Day O’Connor, had mixed records.

When Reagan was president, the conservative judicial talent pool was shallower. It was also more difficult to ascertain whether you were getting a Scalia or a Kennedy. And past Republican presidents had to get their nominees through Democratic-controlled Senates.

Amid a series of setbacks—the rejection of conservative Robert Bork, the near-rejection of Clarence Thomas and a series of successful confirmations for justices who turned out to be more liberal than anticipated—conservative legal networks like the Federalist Society formed. They came to play an important role in tracking conservative legal talent and vetting prospective judges.

Over time, the presidencies of Reagan, George H.W. Bush and George W. Bush also expanded the number of qualified conservative judicial nominees. So there were more people for Trump to pick from and greater effort in helping him make the choice.

It is no accident that Trump had on hand for the Kavanaugh announcement one of the men responsible for the proliferation of well credentialed legal conservatives, former Reagan Attorney General Edwin Meese. “And, Ed, I speak for everyone: Thank you for everything you’ve done to protect our nation’s great legal heritage,” Trump said from the podium.

When Trump was running for the Republican presidential nomination, between his past lifestyle and previous policy positions, there was little evidence he was any kind of social conservative. Yet conservative Christians were an important GOP voting bloc.

To appeal to these voters, Trump promised to name judges whose rulings on abortion, religious liberty and religion in the public square were likely to be in line with conservatives as opposed to the more innovative liberal methods of interpreting the Constitution. Where past Republican nominees simply said they would find judges in the mold of Scalia, Trump—with the help of established legal conservatives—actually named names.

This culminated in the list of 25 possible Supreme Court nominees, crafted with the help of advisers like the Federalist Society Leonard Leo, from which Kavanaugh ultimately came. For all the ways in which Trump has been a departure from the recent political past, on judges his administration has been the continuation—and perhaps the climax—of a decades-long march through the judiciary by conservatives.