Research has shown that it is possible to do something about gray hair. But “gray hair” stands for “old age,” and there is nothing we can do about that, except make it easier to live with. Modern medicine certainly helps. There was no such luck in the ancient world, where the playwright Sophocles described old age as “unregarded, powerless, unsociable, unfriended, where misery couples with misery.”

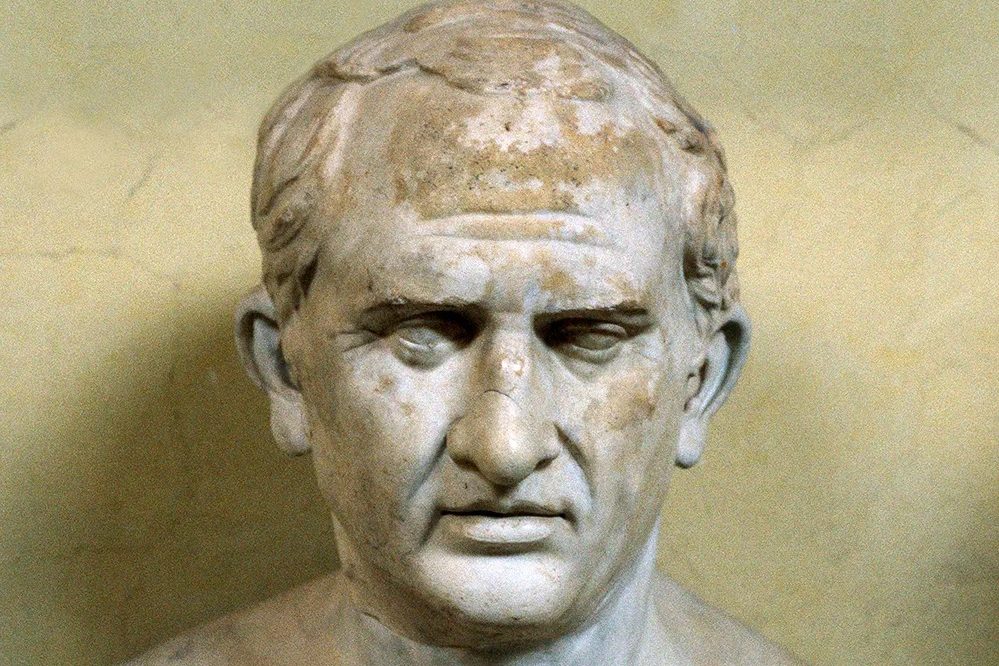

Take Fronto, a close friend of the emperor Marcus Aurelius. He died at the age of sixty, and many of his more than 200 letters mention his physical ailments. Almost every limb was in pain at some stage or other, while he also suffered from gout, neuritis, rheumatism, sore throats, coughs, insomnia, stomach pains and perhaps cholera. Doctors of course could do little about any of this, and even less about old age. Indeed, Pliny the Elder commented that nature gave us no greater blessing than a short life, since people so wracked with illness and decline could scarcely be called “living.”

All the ancients could do was to offer advice about how to face up to it. The satirist Juvenal pointed out how foolish it was to pray for a long life, because the only certainty was that one would complain about how awful it was; if one were to pray for anything, he went on, it should be for mens sana in corpore sano. Pliny the Elder offered the hope of a sudden and entirely natural death, which he regarded as a suprema felicitas. He gave some examples: dying while putting on one’s shoes, or asking the time, or making love to a woman. (His was sudden and natural, though it’s unclear how felicitous: he was suffocated by poisonous gases as he fled the eruption of Vesuvius in ad 79.)

Cicero’s dialogue on old age recommended remaining active both physically and mentally and regarding death as something to be welcomed, “like a ship coming into harbor.” And then there were the funerary inscriptions. One celebrated the sweet repose of the dead, no fear of starving, no arthritis, no debt “and my lodgings are permanent — and free!” Another put it like this: “I was not, I was, I am not, I care not.” And another pronounced: “I died of a surfeit of doctors.” We should be so lucky…

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s July 2023 World edition.