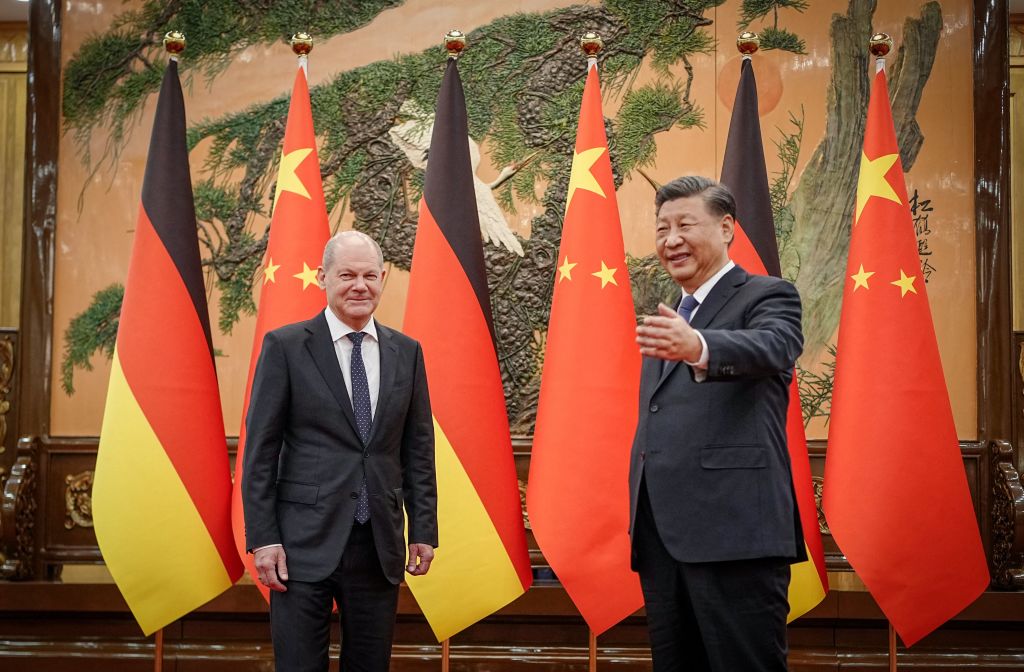

Back in November, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz met with Chinese Communist Party (CCP) chairman Xi Jinping. His visit to China was the first by a G7 leader in three years. Facing heated domestic and international pushback, Scholz framed his visit as an effort to “further develop” economic cooperation between Berlin and Beijing. In this context, such “further development” means further cementing Germany’s Faustian bargain with China, one in which European-based players, like Airbus and Volkswagen, claim immediate revenue — but at their long-term expense and at great strategic cost.

For China, Chancellor Scholz’s visit constituted an opportunity to drive a wedge between the US and Europe by taking advantage of Europe’s current, Russia-imposed economic squeeze and leveraging Beijing’s market as bait. Scholz jumped at the bait despite two decades of precedent showing that Beijing’s promises of market access only ever pan out for China’s champions. In the end, Western companies receive, at best, a few years of profit in exchange for technology transfer, intellectual property theft, industrial dependence, and, ultimately, losing out to Chinese champions.

“In the game with the United States, the West is not monolithic, and the EU is the object worth fighting for,” explained an account of Scholz’s visit in China’s The Paper, before describing Berlin as a pivot player in that effort: “As long as Sino-German relations are stabilized, Sino-French relations can be, as well.”

Europe is not a new target for Beijing. But the CCP sees today’s moment as particularly ripe: Beijing believes that the Russia-Ukraine conflict has exacerbated Europe’s dependence on China. “The EU has lost Russia’s cheap energy. It cannot afford to lose China’s vast market,” argues the article.

And even as European leaders — including and notably Scholz — call for greater economic diversification away from China, Beijing continues to successfully leverage Europe’s industrial dependence to further its strategic agenda. During his visit, Chancellor Scholz signed a framework agreement according to which China committed to buy some 140 Airbus jets.

Chinese media framed this as a play not only to win over Germany, but to do so by manipulating the Airbus-Boeing rivalry. As Chinese logic has it, awarding the European-based Airbus the deal also punishes Boeing for Washington’s increasingly hawkish stance on China. And it serves as a tangible warning sign to Brussels about the risks of taking such a stance. “The Sino-US trade war ushered in the chance for Airbus to overtake Boeing,” explained Chinese press coverage. “Compared with Boeing, Europe’s Airbus is obviously more committed to the Chinese market.”

With this new deal, Beijing secured continued engagement and enthusiasm on the part of Airbus, which already boasts at least five joint ventures with Chinese state-owned companies, two innovation hubs, and a major production base in China — all of which promise to help China’s efforts to develop a domestic competitor to Boeing and Airbus.

This is not the kind of agreement that any G7 leader should be signing right now — least of all the chancellor of Germany, who is seeing firsthand the consequences of industrial dependence on an adversary (and one that Beijing is bankrolling). Scholz’s enthusiasm for this trip, and more generally his embrace of China, constitute a real threat to European security, as well as to the transatlantic relationship.

At the same time, this Sino-German entanglement should be a wake-up call. For the German people, it should raise alarms that whatever hawkish rhetoric toward China the government is adopting, it risks not translating to action. For the European Union, it should underscore Beijing’s confidence in its economic leverage over the bloc. For the trans-Atlantic partnership, this is a direct attack on the part of the Chinese Communist Party.

All parties involved need to look at Beijing’s framing of Scholz’s visit as a reminder that today’s competition is industrial, that as long as production and markets depend on China, so too will national and economic security.

Nathan Picarsic and Emily de La Bruyere are co-founders of Horizon Advisory and senior fellows at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies