To write that George Floyd died is to take a position. The received belief is that he was murdered — a murder bigger, in its consequences, than any other crime for decades. Unlike the relatively muted protests against the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the streets of the world hosted men and women passionate in their denunciation of Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin, whose detention in May 2020 of Floyd by, apparently, kneeling on his neck for around ten minutes, had killed him.

Chauvin became a synecdoche for the perceived repressions of the state — any state, from South Africa to Germany, no matter how strongly committed to democratic governance and civil rights. In Melbourne, in April 2021, while a jury debated Chauvin’s guilt, a vigil was held. In the UK, demonstrators cried, “Don’t shoot! Don’t shoot!” as Floyd had cried when first arrested — this, in the British case, to a wall of unarmed police. US embassies everywhere were surrounded.

Black Lives Matter, founded after several shootings of African Americans at the hands of police officers in the early 2010s, took the lead in the vast responses to Floyd’s death. The movement had a cause, a hero and an emotional watchword — ”I can’t breathe.” Floyd’s last words as he lay on the street, Chauvin’s knee upon him. So widespread was the belief that the police in the US were semi-fascist, trigger-happy murder squads, at least as much an article of faith among white liberals as among blacks, that the spark in Minneapolis became ablaze everywhere.

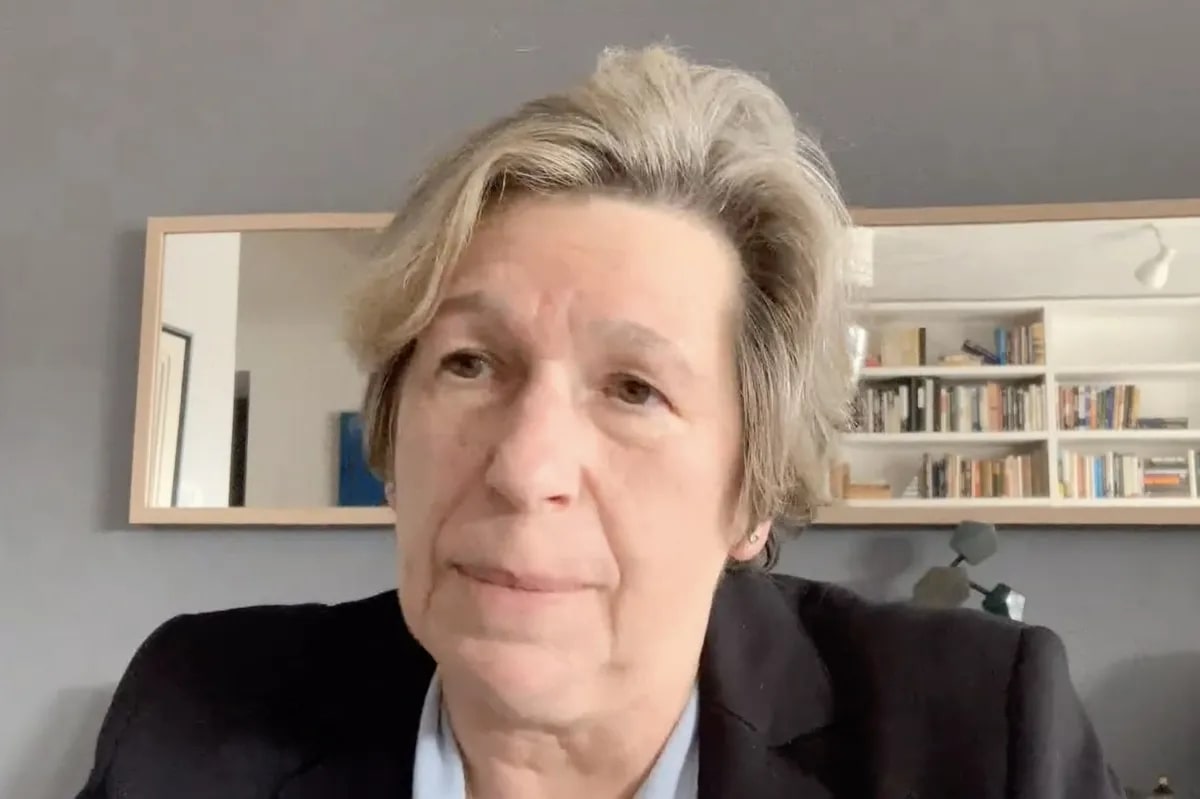

Nancy Pelosi said ‘thank you, George Floyd, for sacrificing your life for justice’

Quickly grasping that this was a cause liberals and the left must be astride, high officials and much of the media strove to identify with the protesters — even where the protests turned, in some cases, to looting and arson, at first referred to as peaceful. The Minneapolis mayor, Jacob Frey, in a tremulous voice, invoked the “agonizing minutes” of Floyd’s death: later, at the memorial, he knelt before Floyd’s coffin, weeping convulsively.

Nancy Pelosi said at an impromptu press gathering that “We saw it happen!” adding, puzzlingly, “thank you, George Floyd, for sacrificing your life for justice.” President Biden signed an executive order aimed at curbing police misconduct, and said that Floyd’s death “sparked one of the largest civil rights movements… in our nation’s history, and inspired the world.”

It also inspired two black American academics, though not in the conventional way. The rapid elevation of George Floyd to martyrdom and the claim of broad unity in the face of white police brutality struck them — while Chauvin began a twenty-two-and-a-half year sentence — as worth examining more closely: unlike Pelosi, for whom “seeing it happen” was not to be questioned, they were and remain not sure of what did happen.

It is part of their self-appointed calling, in their writing and social media presence, to act as burrs under the saddle of demonstrative black victimhood. This rapidly became, for them, as much a mission to unpick the national and global outcries against Chauvin and the police as was BLM’s drive to elevate the death to near Gethsemanean status.

Glenn Loury is an economics professor at Brown University and runs a Substack named the Glenn Show; John McWhorter teaches linguistics in New York’s Columbia University, and has a column in the New York Times. Friends for decades, formerly moderately leftist, moderately concerned about white racism, their views evolved into a strong dislike of the influential view that whites are structurally racist; or, as Jelani Cobb, the dean of the Colombia Journalism School has written in a New Yorker piece about Derrick Bell, that “racism is so deeply rooted in the make-up of American society that it has been able to reassert itself after each successive wave of reform aimed at eliminating it.”

It’s not clear why the two autopsies varied so widely

Since the Floyd trial, the two men have developed the view that the affair has been drowned in a series of performative effusions, a cavalier approach to the case by the Minneapolis justice system and by what Loury calls “the mob” which became the arbiters of what constitutes justice. McWhorter believes that “we have been lied to” by high officials and the media, so that any attempt to view the events of May 25, 2020 on a Minneapolis street in other than the prism of a bloodthirsty police gang is shouted down as racism. In an exchange with Loury, McWhorter has said, flatly, that “Derek Chauvin did not murder George Floyd.”

Their belief in the mendacity of what has become the official version of Floyd’s arrest and death is much strengthened by a film, The Fall of Minneapolis, written and directed by the writer JC Chaix and produced and reported by investigative reporter Liz Collin. In close on two hours of documentary with multiple interviews, clips from the body cameras of the arresting officers and excerpts from documents, the film underscores that the judge, Peter Cahill, refused to delay or move the trial to avoid influence on the jury by the huge coverage of the case, banned some evidence from an earlier arrest of Floyd and would not allow evidence that Floyd had called out to his mother (who had died years earlier), a possible indication of confusion caused by an intake of drugs.

The first autopsy on Floyd by Hennepin County medical examiner Andrew Baker argued that the ingestion of fentanyl and a heart condition were contributory elements to Floyd’s death — together with the pressure on his neck. A further autopsy was commissioned by the family of George Floyd, which found that the death had been due to asphyxiation caused primarily by pressure on the neck: it’s not clear why the two autopsies varied so widely.

The police body cameras appear to show that Floyd, who had a series of previous convictions and had been arrested for allegedly passing counterfeit money in a store near where he was detained, was wildly intoxicated, refused to obey police instructions and had shouted several times “I can’t breathe” when standing up or resisting efforts to put him in a police car. The signature phrase is thus reduced from a dying cry to a possible outcome of drug use.

The police called for an ambulance for Floyd shortly after his arrest: but due to confused messages, it did not appear, though stationed a few blocks away, for nearly ten minutes — by which time Floyd may have been dying. Footage shows two policemen trying to revive him in the ambulance.

Minneapolis police chief, Medaria Arradondo, said on oath in court that his department gave no training on holding a suspect down with the knee after they had been restrained — yet the then current training manual, in section 5-316, appears to show, alongside an accompanying training slide used in Minneapolis, just such a procedure — not one widely used by other police departments, and now dropped by the Minneapolis police.

The clip of Chauvin holding down Floyd, with millions of views, closely resembles these directions. The clip seems to show that Chauvin’s leg was holding down Floyd’s shoulder, with the knee either on or slightly above the neck. Taken together with an autopsy report that the neck showed no damage, it renders the judgment of murder by asphyxiation less certain than the version promoted by the prosecution and accepted by the jury.

The trial took place in a hyper-tense atmosphere. A crowd of thousands stood outside the court throughout: Congresswoman Maxine Waters, among the protesters, told journalists that, if a guilty verdict were not returned, “we’ve got to stay on the streets and… get more confrontational”

In a series of interviews with policemen and — women — all of whom had resigned after the trial — The Fall of Minneapolis film dwelt on the revulsion officers felt for the verdict and more, for what they saw as their desertion by the mayor, the Minnesota governor Tim Walz (who had said, referring to the clip of Chauvin with his knee on Floyd, that “The lack of humanity in this disturbing video is sickening” and the police chief.

The trial took place in a hyper-tense atmosphere

The film also had dramatic footage of a prolonged attack by protesters on Precinct 3, in which the four officers attending the Chauvin arrest were based and from which all officers had been ordered to leave, abandoning the station to the fury and wreckage of the protesters. An interview with Chauvin’s mother elicited the comment that “I no longer believe in justice here” — repeated by several of the police interviewed, including the two black officers.

Yet, as Loury admitted in an interview with me, doubts remain on his and McWhorter’s side: deepened by a message to Loury from Minnesota attorney general Keith Ellison, who underlined the testimony of a witness, Dr. Martin Tobin, a respiratory specialist. Tobin had testified that Floyd did die from asphyxiation, even if it did not show in the initial autopsy. Loury got the filmmakers Chaix and Collin on the Glenn Show, and asked them to defend their belief in the radical unfairness of the court case: Chaix, the main speaker, said that Tobin was in the realm of conjecture — since it was Baker who had performed the initial autopsy. Loury told me his doubts still remain — though he wrote on his Substack, after a talk with the filmmakers containing “no softballs,” that “in my opinion, their story holds up.”

What we are left with then is a judgment substantially crafted by prior elite approval of guilt and hustled by a militant crowd daring the outcome to be other than an exemplary sentence for murder. Enough, one would think, for an appeal in less fervid times.

McWhorter and Loury, pitted against the victimhood narrative, have for years sought to popularize a black American cast of mind — still experiencing a residue and in places more than a residue of racism — as still one of opportunity and a source of pride. “This is my country!” Loury said to me. The two scholars believe that black Americans should accept this: that racism is now residual rather than structural, that the way to self and communal material betterment is now largely the responsibility of the individual, and that the black American communities should support such a view as one more likely to improve the lives of all American people of color — and of American whites. This would entail seeing whites as differing individuals rather than, as taught in some versions of Critical Race Theory, an undifferentiated mass of actual or potential racists.

The Floyd affair, however, remains stuck, presently, in what seems like a worldwide belief in unchanging black American victimhood: yet there’s some hope that the two professors’ activism may shift that to one which relies on facts and even fact-based faith in American policing and civil society, not on belief of immovable prejudice. Derek Chauvin, meanwhile, is recovering from serious injuries after he was stabbed in prison by a fellow inmate.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.

Leave a Reply