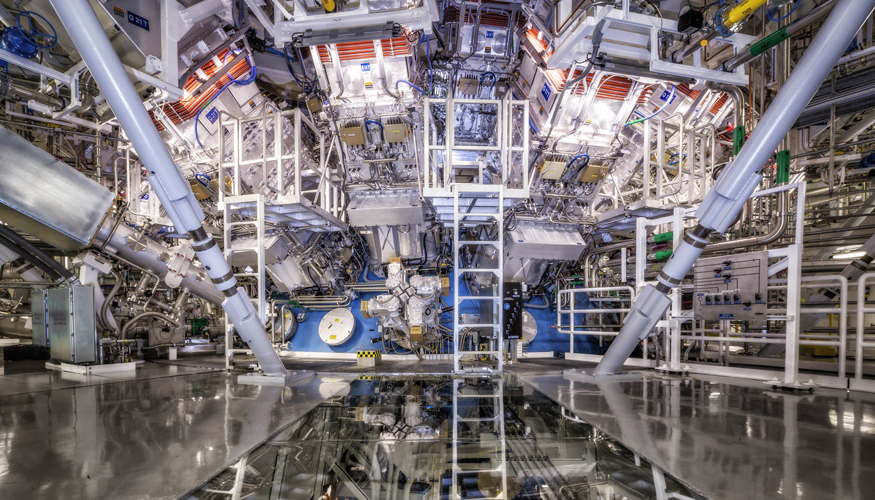

Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm will announce a major breakthrough in nuclear fusion on Tuesday. Over the last two weeks, the National Ignition Facility of the federal Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California shot three lasers at a deuterium-tritium fusion fuel pellet, heating it until it induced a fusion reaction. This particular fusion reaction generated more power than used in the lasers shot at it.

Granholm will hail this as a “major scientific breakthrough.” And it is. But we’re still a long way away from the promise of bountiful clean energy that fusion promises.

Let’s put the breakthrough in perspective. It appears the fusion reaction generated 2.5 megajoules of energy while the lasers spent 2.1 MJ. But NIF’s lasers are huge and less than 1 percent efficient. To outstrip energy spent in a useful sense, you’d have to yield one hundred times more energy.

Then there’s the not insignificant question of what kind of energy was generated. “The fusion power is in the form of heat and radiation, and needs to be converted back to electricity,” explains Wilson Ricks, a Ph.D. candidate studying Macro Energy Systems at Princeton. “Assuming a 40 percent steam cycle efficiency, that’s another 2.5x increase in required yield. So we need a fusion reaction 250x more powerful to achieve true electric net gain.”

Lastly, the process of getting to electricity generation from fusion would involve the messy iteration of developing complex engineering projects for commercial use. That always takes longer than advertised. A running joke in the energy sphere is that every year we’re twenty-five years away from fusion.

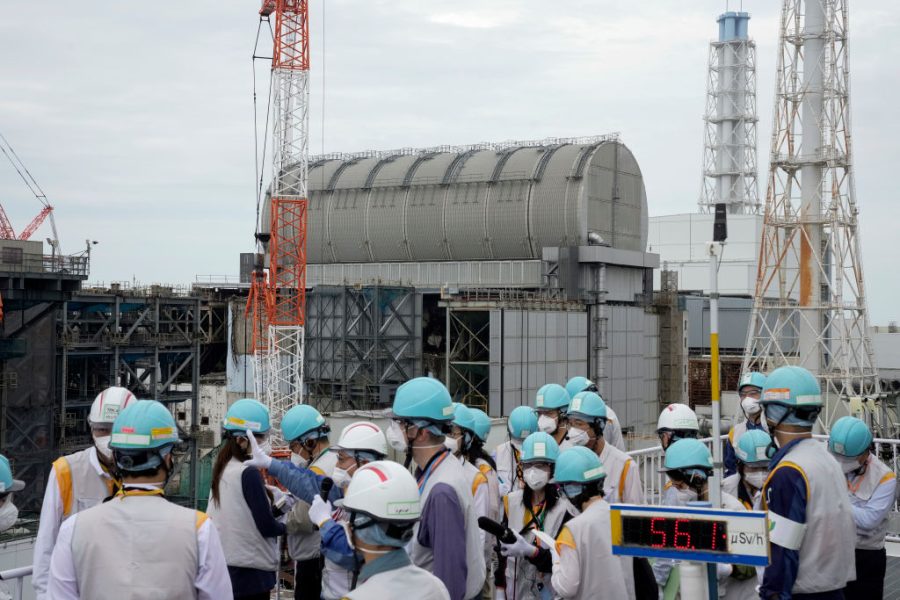

So, if it’s going to take so long, why is everyone so excited about this breakthrough? The short answer is because of the promise of fusion, which offers us abundant clean energy without long-lived waste. It’s also more meltdown-proof than nuclear fission. Plus, as fusion advocates often point out, it’s not connected to nuclear weaponry.

But the fuel for nuclear fission is already abundant — it’s about 2 million times more energy dense than hydrocarbons like oil or gas. Waste storage for spent nuclear fuel is a political problem, not a technical one: all the nuclear waste in America, if stacked up, can fit in a football field. Plus, fission is already one of the safest forms of energy ever crafted by the hand of man — second only to solar. And the weapons issue remains: fusion adoptees could use the fuel cycle to cultivate fusion bombs.

This isn’t to detract from the scientific achievement at National Ignition Facility, nor is it an argument against fusion. We should continue to explore its potential because societies that cease to invest in their own future cease to survive. Committing resources to producing energy abundance for posterity is a high economic, strategic and moral priority.

But science doesn’t move at the speed of ad copy — which is what most energy coverage is these days. Especially when it comes to tech. For now we have fission. We should work on figuring out how to liberate the atom from the regulatory shackles that have imprisoned it and how to become the kind of country that can build advanced engineering projects again. If we don’t, how will we ever achieve fusion?