Across France this Easter families will gather to eat, drink and, in many cases, smoke drugs. There are five million regular cannabis smokers in France and a further 600,000 who are classified as cocaine addicts.

The number of people who consume wine on a regular basis is just over 7 million (11 percent of the population), a figure that has been in freefall this century.

In the past sixty years the consumption of wine has plummeted in France, from thirty gallons per person per year in 1960 to less than 10 gallons in 2020. The beret and string of onions round the neck was always an Anglo-Saxon stereotype about the British but not so their love of wine. While Brits would nurse their pints of stout or bitter, the French would uncork a bottle of red.

The power and wealth of the drug cartels in France has rocketed

No more. In the last ten years the number of regular wine drinkers has fallen by 32 percent, resulting in brutal ramifications for the major distributors. The sale of Bordeaux wines is down by 35 percent in the past decade, while it’s 31 percent for Côtes-du-Rhône and 29 percent for Pays d’Oc red.

Champagne has also gone flat. In 2023 there was a 20 percent fall in sales, although this was partly attributable to an increase in price, on average 10 to 12 percent a bottle.

But the decline of wine consumption is a cultural phenomenon which, according to one of France’s leading sociologists, Jerome Fourquet, has had dramatic social and economic consequences. In his 2019 book, L’archipel francais, Fourquet noted that France’s biggest wine region, Languedoc-Roussillon, has lost 43 percent of its production surface since 1975 because of the dwindling demand for wine. The number of wine cooperatives has fallen from 550 in the 1970s to 200 in 2012. Once the cooperatives were at the heart of communities, along with the church and the rugby club.

It is a diminution that shows no sign of abating. In an interview last October Denis Verdier, the president of a wine federation in Languedoc-Roussillon, said: “The crisis is here, but we won’t give up… we must and we will innovate.”

Easier said than done when an increasing proportion of the population doesn’t drink alcohol. Last year this figure was nearly one in five (19 percent), an increase of four percentage points since 2015.

France’s shift has undoubtedly been influenced by immigration this century and the growing number of Muslims. In 1950, for example, there were 230,000 Muslims in France; seventy years later there are 6,635,327.

This is also a significant factor in the rise of cannabis as the drug of choice for the French youth.

In L’archipel francais, Fourquet states that thirty years ago, only one in five seventeen-year-olds in France had smoked cannabis: now it is one in two. Consumption among the adult population hasn’t risen quite as steeply, but whereas in 1982 only 4 percent of eighteen to sixty-four-year-olds had smoked cannabis, today it’s 45 percent. No other country in Europe smokes as much weed as the French.

This century, the power and wealth of the drug cartels in France has rocketed to the point where commentators and politicians talk of the “Mexicanization” of France. The French economy might be in turmoil but one industry is booming and that’s the drugs trade. Figures released this week estimate that the market generates a turnover of around $3 billion a year, and France’s anti-drugs agency believes that 240,000 people make their living directly or indirectly from drug trafficking, 21,000 of whom are full-time workers.

The men who run the cartels in France base their HQ in Morocco (the world’s biggest producer of cannabis resin) and they like to employ illegal immigrants as their dealers. In November last year a cartel in Nice was dismantled in a vast police operation and 60 percent of the dealers were in France illegally. Earlier this month, police scored another victory when, working with their counterparts in Morocco, one of Marseille’s biggest cartel bosses was arrested in Casablanca.

Nonetheless, when France’s minister for the economy, Bruno Le Maire, appeared before a senate committee on Tuesday he gave a bleak assessment of the situation: “Let me be clear: drug trafficking represents a major threat to our national security, which I consider to be as serious as the threat of terrorism.”

Le Maire went on to outline various measures which the government plans to introduce to combat the traffickers.

But that’s only half the battle, as Emmanuel Macron admitted last year. “We can’t complain about drug trafficking if we have drug users,” he said. “People who have the means to take drugs because they find it recreational must understand that they are feeding networks and that they are in fact complicit.”

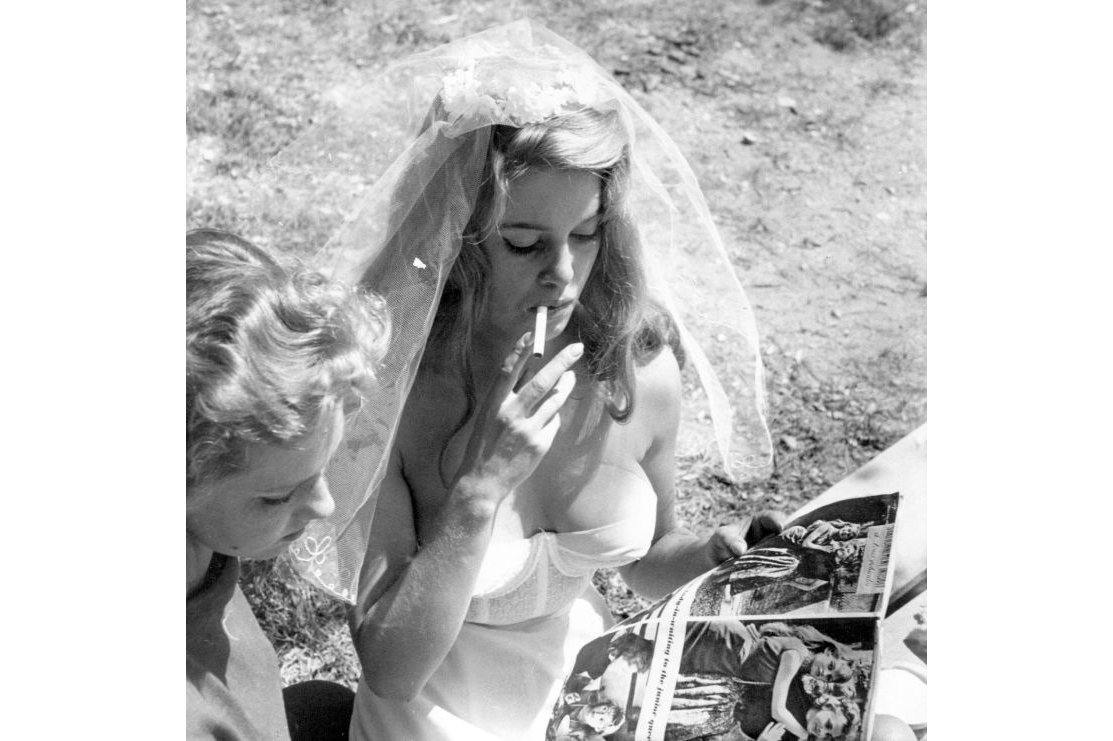

France’s young pot smokers don’t care. For them, a joint is what a glass of red was for their grandparents’ generation.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.

Leave a Reply