I am actively contributing to the decline of the West and to the collapse of our civilization. I realized this last week when I found myself standing behind a metal turnstile in the French Alps watching my smallish son, on the other side of the turnstile, step into a bubble lift going up the mountain to the nursery slope. He was with an instructor from the French Ski School, the ESF, surrounded by other children and entirely safe. He’s just turned seven, yet I behaved like a distressed cow watching her calf hauled off to market. I weaved and bobbed trying to keep him in my line of sight; craned over the barrier with mad, staring eyes. My son’s class was les flocons, the snowflakes, and each child had a large snowflake printed on his yellow bib. Some small part of me recognized how comically fitting that snowflake was, even as I barged my way past an elderly couple into the next bubble car and waved frantically through the window at my son’s receding form. Up on the mountain, I stalked the little flocons, tracking my son’s red trousers. What if he fell, lost sight of the guide or slid backwards into the lift machinery?

Why do those of us who grew up independent and resilient deny our kids the freedom we valued so much?

I’m not proud of this behavior. I know it’s shameful. I mention it only in the interests of research.

On our flight out I read a blog by the psychologist Jonathan Haidt in which he outlines the subject of his next book, an attempt to understand why it’s the children of the Anglosphere who are so especially anxious (provisional title: Kids in Space). Back in 2018 Haidt and his co-author Greg Lukianoff published The Coddling of the American Mind, which detailed the crisis facing Gen Z in the US. The trouble with the kids, explained Haidt and Lukianoff, is that they’ve come to believe three great untruths. The first untruth is that they themselves are fragile and easily damaged. This is why they think “misgendering” and “micro-aggressions” cause actual harm. The second is that their own feelings are a reasonable guide to reality, and the third is that life is a constant struggle between the oppressed and the oppressor, good and evil — hence the popular notion that anyone in power is a scumbag and all minorities are pure as the driven snow.

If you fancy a look at these untruths in action, just dig out the video from a few days ago of student activists screaming at the female swimmer Riley Gaines. The fact that Riley even holds the view that trans women should not compete in women’s sports is so overwhelming to the kids that they ululate and shriek like the survivors of a massacre.

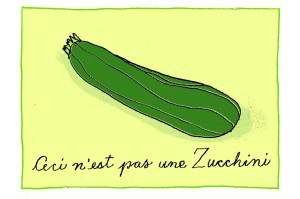

Haidt’s new thesis, based on data from surveys and from our health services, is that this emotional fragility stretches particularly across the English-speaking world: America, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the UK. He blames smartphones — not screen-time per se but the fact that screens have displaced other healthier activities — and he blames parents. If the Anglosphere is producing snowflakes, it’s because mothers like me have bred them. British parents are different — more coddling than other Europeans, he thinks — and my week in the Alps only goes to show he’s right.

As I took the bubble lift back down into the valley I thought of a parenting book given to me by a good friend when I was pregnant — the only one I’ve ever read or felt the need to. It’s by an American, Pamela Druckerman, who moved from the US to Paris with her daughter, and it describes how extremely and amusingly self-possessed French children are, relative to their American peers, and how little their parents micromanage them. French Children Don’t Throw Food, it’s called. Someone should write another: French Ski Guides Don’t Look Back. I noticed during the week that the men and women of the ESF don’t fuss and chivvy, they don’t obsessively count their little charges or tick them off a list, they simply lead from the front and trust the flocons to bob along behind them. It’s extraordinary to English eyes. Perhaps French parents don’t sue? But then, nor do they catch the next bubble lift so as to show their child they’re not alone, or beat on the plexiglass like Dustin Hoffman in the final scenes of The Graduate. They just kiss their three-year-olds and leave, and because they assume that their children can take care of themselves, for the most part they do.

A while ago I signed up to Haidt’s Let Grow project, which asks panicky western parents to make a pledge to give their kids some freedom. “We make a commitment to step back! We will allow some frustration and imperfection!” Since I made that promise, I now realize, the only parenting resolution I’ve really kept is to make sure that there’s an Apple AirTag tucked in my son’s trouser pocket whenever he’s off on a trip. I dimly remember that I once thought it creepy to secretly track a child. Now it seems to me a reasonable thing to do.

What about Britain, America and Australia encourages this paranoid style in parenting? Why do those of us who grew up independent and resilient deny our kids the freedom we valued so much? I’m looking forward to the answers Haidt provides, and all I can advise him is that it’s going to take more than a parent pledge to save future generations. We snowflake-makers are masters of self-deception.

On day two of ESF, after resolving firmly to be more French, I disgraced myself again. As I went to follow the flocons up in the bubble once more, I realized I’d left my pass behind. The turnstile wouldn’t turn. Did I take this opportunity to let go and let grow? I did not. I was seized by vision of my son waiting for me at the top like Greyfriars Bobby, refusing to budge until I appeared as promised to wave him off. So I waited until the lift operator’s back was turned, and jumped the barrier. At the top, heart pounding, I leapt from the lift just in time to see him rounding the corner, hard up on the teacher’s heels, not looking back.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.