Francis Fukuyama never reads the comments. He is a benign presence on social media, whether it’s on Twitter, or Instagram. Now I know why. Unlike many public thinkers, Fukuyama is not that interested in joining the digital fray. He reckons that a third of comments on his posts ‘are going to be stupid references to The End of History — “this is not the end of history, is it” — so I’ve avoided the temptation to get into fights.’

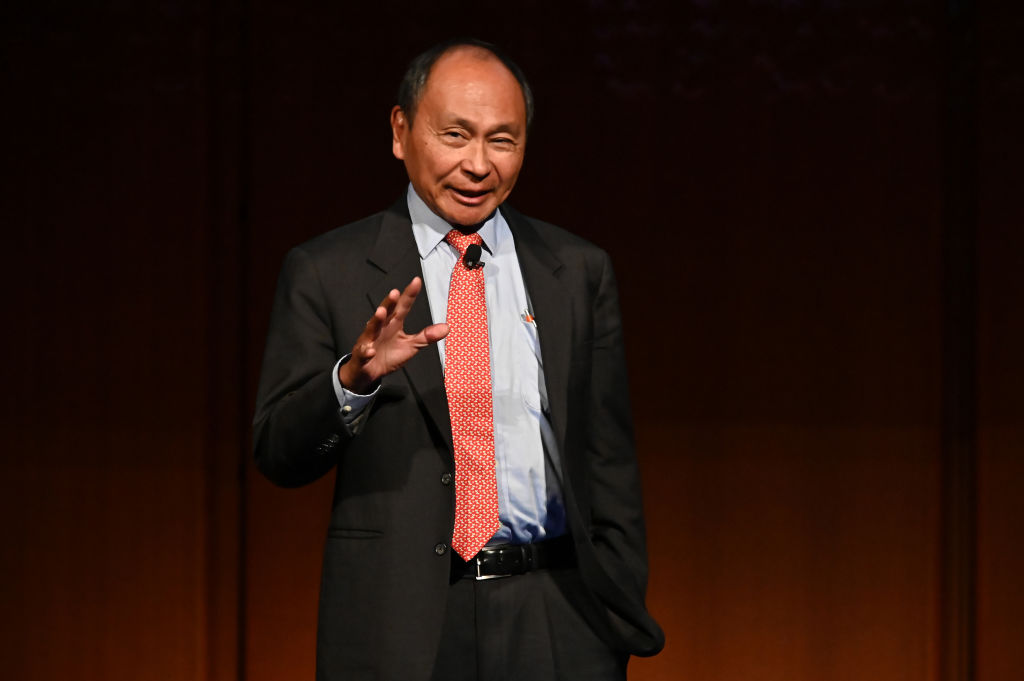

I’ve called Dr Fukuyama — permanently assured of a place in the history of ideas since his essay “The End of History?” appeared in 1989 — to talk about his hobbies.

Great minds need to rest. Socrates enjoyed dancing. Diogenes was a keen sunbather. Immanuel Kant was a dedicated pipe smoker. In April, my colleague Cockburn reported that Fukuyama builds his own furniture and tinkers with a truly robust home computer setup. Judging by this powerful processing equipment, Cockburn wondered if Fukuyama was a gamer. The answer, when it came, was definitive:

FYI I am not a gamer. However I have built my own hardware and written my own software for 25+ yrs, can program arduinos and raspberry pis, and am getting back into 3D modeling and animation after a hiatus: https://t.co/aJbwUpJmnV

— Francis Fukuyama (@FukuyamaFrancis) July 17, 2020

Speaking from California, Fukuyama once again assured me that he was not a gamer. He began making furniture in the early 1990s, after moving to Virginia. ‘I wanted to make stuff because I felt that creating something tangible, that’s useful, is a good corrective to the abstract intellectual work I’ve built my career around.’ Fukuyama’s inspiration was elegant Federal-style furniture found in a suite at the State Department, where he worked in the 1980s. ‘I’d always admired these objects but couldn’t possibly afford to buy furniture like that. So I decided I would teach myself how to make it. I never took any classes, I had books and videos.’ When a walnut tree came down in the Fukuyama’s backyard, he cut it up with a chainsaw and spent three years drying the wood, which became a pair of inlaid Pembroke tables. ‘That was probably my most ambitious effort,’ he says, wistfully.

During the shutdown, Fukuyama spent more time on his other passion — computers. He’s been building his own hardware for a couple of decades. Recent upgrades mean they’re now ‘super powerful’ and ready for the demands of online teaching. The technology connects with woodworking; Fukuyama planned the furniture he wanted to make by first constructing digital versions using AutoCAD. ‘I started getting into this further,’ he says, ‘I realized that once you made these models you could situate them in an architectural space. So then I started building houses that would be appropriate settings for these furnishings.’

I ask Fukuyama if the distinction between techne and nous, between the practical and the intellectual, is a false one. Doesn’t he combine them? Not really. ‘It depends very much on your personality. I think that a lot of my academic friends, they don’t even — when they have to repair a toilet or something like that — it just does not occur to them that they could teach themselves to do this. I think there is a distinction.’

Work in America has grown more abstract, and not just for academics. As early as 1956, more Americans were employed in administration than in agricultural and industrial production combined. Long before the ‘knowledge economy’ was hailed in the 1990s, this trend — an artificial quality to working life — was identified. A divide between blue collar and white collar occupations widened. The late John Lukacs called this process ‘the insubstantialization of matter’. The life of the median person, Lukacs thought, was probably more abstract than at any point since the High Middle Ages.

Fukuyama thinks that’s right. He cites Matthew Crawford’s Shop Class as Soulcraft as a book that illustrates what was lost when schools all over the country replaced shop class with computer class. ‘There has been a huge cultural shift. One of the consequences is its contribution to the economic inequality that has risen steadily for the last three decades.’ The economy still needs people with sophisticated manual skills, like welders, but the education system is no longer producing them. Fukuyama thinks the problem is partly cultural. Apprentices in the US do not have the cultural dignity of their equivalents in Germany or Japan, where skilled machinists are still respected. ‘There’s a Japanese national prize,’ he says, ‘where they pick a hundred individuals who they think are exemplars of skill and Japanese culture. Mechanics often win. In America we would never do that.’

Fukuyama speaks as he writes, with clarity and precision, plucking cases for his arguments as he ripples over continents. Though he will forever be associated with the triumphant 1990s for some, this misses a deep current of Weltschmerz in his writing. ‘The end of history’ he wrote in 1989, ‘will be a very sad time. The struggle for recognition, the willingness to risk one’s life for a purely abstract goal…will be replaced by economic calculation, the endless solving of technical problems, environmental concerns, and the satisfaction of sophisticated consumer demands.’

This fear that sloth and apathy multiply under the canopy of a safe, advanced civilizations was felt by other thinkers. Nietzsche wrote about the last men — ‘men without chests’ — who live empty lives of routine and comfort. In 1759, Adam Smith regretted that the ‘general security and happiness which prevail in ages of civility and politeness’ gave ‘little exercise to the contempt of danger, to patience in enduring labor, hunger and pain.’ The ground eventually splinters beneath such societies. It is the bored, restful England of ‘delightful measures’, ‘merry meetings’ and ‘idle pleasures’ that gives birth to the monstrous tyrant Richard III in Shakespeare’s play.

‘I think I wrote something like this in The End of History,’ Fukuyama says, ‘you know, people want to struggle for justice, and if they can’t get that in a liberal democracy then they will struggle for injustice. What they want to do is struggle.’ He thinks Poland, a success story in terms of economic growth, now with the populist Law and Justice party in power, is a good example of a country ‘taking democracy for granted’. This turn indicates ‘that peace and prosperity under a liberal democratic regime are ultimately not that satisfying. People have other aspirations to do with their dignity and their identities that don’t necessarily get recognized.’

As withering as Fukuyama is about populism, he also takes aim at extreme identity politics. Last month he was one of the signatories of the Harper’s letter on free speech. What did he make of the controversy that surrounded its publication? ‘I thought that the reaction to it demonstrated some of the pathologies that it was warning against, that is, signatories being blamed not for what they were saying, but for merely being associated with unpopular people.’ The squabble was a sign of the ‘fissure that’s opened up between traditional liberals and woke progressives’. At the moment he thinks that the most outlandish forms of identity politics are still confined to cultural elites. But he anticipates that ‘the whole world is going to shift to the left in the next few years and we will, perhaps, see more powerful versions of this’. A decisive turn from class politics to identity politics is underway.

[special_offer]

He says he’s moved to the left on economic issues, but he worries about where the left is devolving culturally. ‘I anticipate I’m going to be getting into fights on those sorts of issues in the future.’ It’s easy to pick fights over symbols, and relatively costless. ‘I think it makes us lazy thinking about removing a statue, rather than creating a social policy that will materially improve conditions for marginalized groups. That’s what you ought to focus on. The cultural stuff becomes a diversion.’

I ask if he can say this to his students at Stanford.

‘In the aftermath of the George Floyd killing, it was hard to have a conversation about anything.’

Well, I suggest, rather weakly, you have plenty of hobbies to occupy you if things in public life get too crazy.

‘That’s right.’

On Monday, Dr Fukuyama resigned as chair of the editorial board at the American Interest, which he helped found in 2005. It seems there’s a good chance he will enter the fray after all — just don’t expect it to be on Twitter.