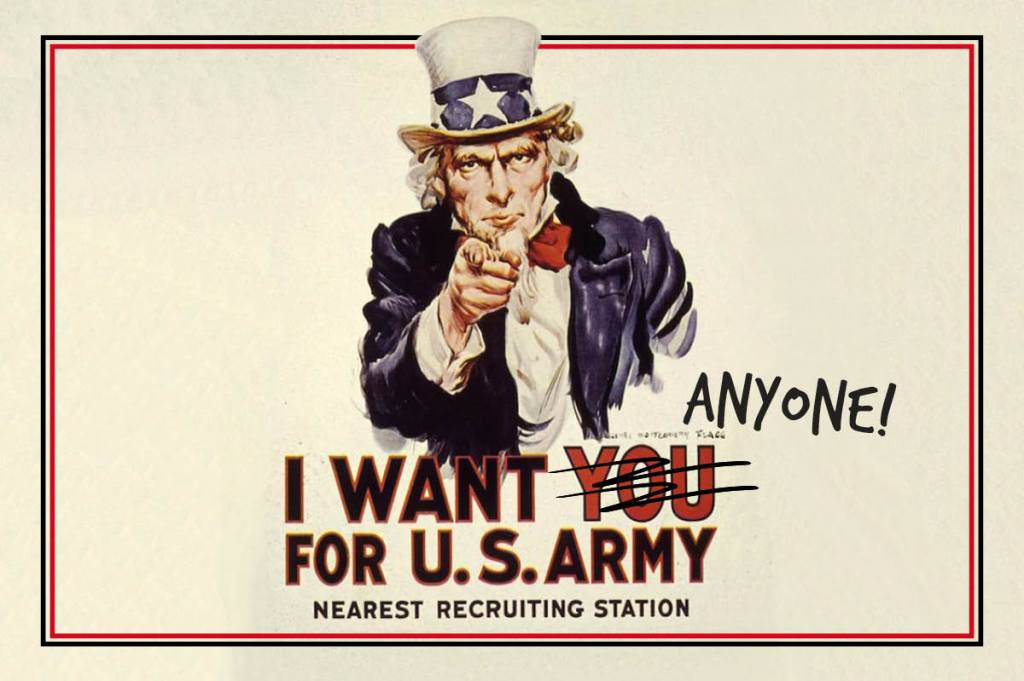

Our military is facing the worst recruiting crisis in the history of our fifty-year-old All-Volunteer Force (AVF). Contrary to what you may have read elsewhere, there is no single explanation for this urgent problem. Rather, this crisis is the product of a number of factors: a strong civilian labor market, the effects of COVID, a shrinking pool of American youth eligible to serve in the military, and — of greatest concern — a reduced interest in joining the military, fed by a lack of knowledge, a declining sense of service, false and negative messaging about the forces, and the activist politicization of the force.

Today, there are about 1.3 million active-duty military members; they are its greatest asset. The services aim annually to match their respective personnel numbers with their congressionally authorized “end-strength” headcount. As the largest branch (about 35 percent of the military), the US Army has a substantially higher recruiting goal than the other services. Since the start of the AVF, the services have generally acquired enough qualified recruits. But the 2022 fiscal year was the worst for military recruiting in the AVF’s history. The Army missed its recruiting goal by an astounding 25 percent. It received 44,901 soldiers, 15,099 (75 percent) less than its goal of 60,000. The Navy gained 33,442; the Marine Corps 28,608; the Air Force 26,196; and the new Space Force 532. While the other services met their fiscal 2022 goals, it was a tough year for recruiting. All bolstered retention efforts to meet their end-strength.

The bad news only gets worse. It was recently announced that the Army, Navy, and Air Force will all miss their fiscal year 2023 enlistment goals. Throughout the active and reserve components, the Army expects to fall 10,000 recruits short, the Navy 6,000, and the Air Force about 10,000. Army active-duty numbers fell in 2022 and will again — perhaps by as much as 20,000 — resulting in a significant (up to 7 percent) decrease in force size over just two years. The current dramatic shortfall is part of a downward trend, particularly for the Army. In 2018, the Army missed its recruiting goal of 76,500 by 6,500, and in 2019, 2020, and 2021 the Army met goals which had been lowered each year. Defense experts warn that the lack of personnel — especially for the Army — is a serious threat to readiness and national security.

A solid labor market has clearly hurt recruiting. Historically, the military faces greater recruiting challenges when the unemployment rate is low, as it is now. COVID worsened the problem. Military recruiting is recovering from two years of shutdowns and isolation, in which recruiters lost in-person access to prospects at schools, public events, and military-focused youth organizations such as the Sea Cadets and JROTC programs. Virtual recruiting was less effective, and recruiters have found recovery in many in-person venues slow.

A longer-term trend that makes things difficult is a shrinking pool of eligible recruits. Only about one in four young adults between seventeen and twenty-four meet the minimum service entry requirements: citizenship or being English-speaking, green card-holding permanent residents within the age limits; a minimum score on the Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery (ASVAB); a high school diploma or GED; medical and physical fitness; and good moral standing. Drug use, obesity, and physical and mental health problems are all on the rise, while ASVAB scores are falling.

These problems should be surmountable. For example, obese, motivated people can get into shape. During one Navy assignment, my building included a recruiting center. Several mornings a week, I saw groups of aspiring (and perspiring) overweight recruit candidates jogging in formation, a recruiter alongside them shouting encouragement. And the military has weathered a strong labor market before, is recovering from the COVID-era loss of access, and, depending on trade-offs, some entrance requirements might be lightened. But a fourth factor makes today’s crisis particularly alarming.

In response to low youth eligibility rates, the Army’s vice chief of staff delivered the worst news: “Fewer still, we’re finding, are interested in serving.” DoD Youth Surveys on “propensity to serve” show that only about nine percent of sixteen-to-twenty-one-year-olds consider military service “likely” in the next few years. Despite a few upticks, this propensity has declined steadily since the 1980s. Over the past four decades, male service propensity dropped from the 24-27 percent range to today’s 11-14 percent range.

Several factors drive low propensity to join. The first is shrinking awareness. An unintended effect of the AVF is that the military no longer represents a swath of the country. A full 50 percent of American youth know little or nothing about military service. Most are increasingly disconnected from, and not exposed to, the military. A growing “military-civilian divide” hinders recruitment and maintaining the force. The best predictor of enlisting is not socio-economic class, race, or even the youth employment rate, but a person’s familiarity with the military. Only one percent of the population currently serves in the military, and most enlistees (80 percent) have a family member who is or was in the military. Veterans, who help inform youth of the military, are a shrinking population.

Youth awareness of the military is concentrated in certain areas of the county with a higher military population. Youth in the southern US, where the tradition of military service is higher, enlist at two to three times the rate of other regions. Conservative-leaning areas are more fertile ground for recruiting than liberal-leaning ones. Army recruiting is trying to make headway in liberal-leaning cities, but it’s a challenge. In Seattle, recruiters who ventured onto a public community college were taunted and chased off campus by “antiwar, counter-recruiting teams.”

Low propensity to enlist is worsened by the young generation’s declining patriotism and sense of duty to the country. If high school students are barely taught civics and US history, let alone the role of the US military in the world’s defense of freedom, is it any wonder this generation is so little interested in enlisting? Over a third of eighth-grade students have reportedly never taken a civics or history class, only 22 percent have proficiency in civics, and only 13 percent are proficient in history. I recently heard it said that “Gen Z is not impressed with the military.” Not a surprise since so few of them know what it is.

False and negative messaging also dampens the inclination to enlist. With fewer military-experienced influencers, youth perception of the military increasingly reflects messaging from Hollywood, the media, politicians, special interest groups, and higher education institutions that often portray the military negatively. Public misperceptions include that the military is racially and ethnically intolerant; against gender diversity; not inclusive; primarily a refuge for lower socio-economic groups with no better alternative; and a home for extremists.

The reality is different. Military recruits are more racially and ethnically diverse than ever before. In fact, in the US Army, African Americans and Hispanics are overrepresented compared with their share of the US population. Most recruits come from the country’s large middle class. Female representation, including at the most senior ranks, has been steadily increasing. And, despite messaging that the military suffers rampant extremism, a recent review of DoD records found that less than 100 members (equivalent to 0.005 percent of the active and reserve military) were found to have engaged in prohibited extremist activity.

Recruiting has also suffered from declining trust in the military. A Gallup poll and a 2022 National Defense Survey find a drop in public confidence in the military in recent years. The later survey finds less than half (48 percent) of Americans have a “great deal” of confidence in the US military, a sharp drop from 70 percent in 2018. The survey also found the public lost confidence in the military because of “Military leadership becoming overly politicized” (34 percent); “So-called ‘woke’ practices undermining military effectiveness” (30 percent); and “So-called far-right or extremist individuals serving in the military” (23 percent).

There’s no doubt that politicization is undermining recruiting. Some Democrats have condemned the military for alleged racism, extremism (which they link to Republicans), and resistance to new diversity initiatives. Some Republicans say reports of such problems are exaggerated, that the new diversity initiatives aren’t based on proven effectiveness, and that “wokeness” detracts from military readiness. What’s clear is that special interest groups have used political pressure to promote their own agendas, often under the guise of “improving military readiness.” The tactic is to accuse the military of wrongdoing, implying guilt exists, and then demand a change.

A glaring example is the Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) requirements added to the military’s existing equal opportunity-related policies. In 2022, the newly created Defense Advisory Committee on Diversity and Inclusion was tasked to take “immediate actions that can be implemented to support a

more diverse and inclusive force” and to make “transformational change that will become part of the Department of Defense’s DNA.” The creation of this committee basically is an accusation that the military is failing to be sufficiently diverse. Similarly, the February 5, 2021 administration order for a military stand-down to search for extremism in the military was an implication that the military must be guilty of extremism. As mentioned earlier, the facts simply do not support these claims.

Any wrongdoers should be dealt with, certainly. And the military has policies and legal codes to prohibit inappropriate or dangerous behavior. But US leaders genuinely concerned with improving military readiness and recruiting should inform the public of the full truth of the situation and not let such incidents falsely obscure the equal-opportunity success story of today’s military.

Promoting a culture focused upon differences such as skin color or gender damages a military reliant upon mission-focused unity and teamwork — not internal rivalry.

I have worked in private companies, the federal civil service, and served in the military. In my 20 years in the Navy (thirteen years on active duty), serving alongside diverse officers and enlisted sailors, I found the Navy a model of inclusion. Not perfect, but color- and gender-blind in a way that few other organizations can claim to be. When someone walks in the room, the first thing you look at is the person’s collar or shirt markings. The uniform and military title (not their color or gender) inform you of that person’s level, specialty, experience, and authority.

The recent politically driven focus on divisive and peripheral cultural issues has hurt the trust of service members in the institution, with chilling implications for retention and recruitment. A recent survey found 65 percent of active-duty members are concerned about “growing politicization of the military.” One of the most cited areas of concern (41 percent) is “an over emphasis on diversity, equity and inclusion programs.” The poll also found active-duty military members’ trust in the military has decreased due to recent events. The top five events cited were: allowing unrestricted service by transgender individuals in the military (80 percent); the withdrawal from Afghanistan (71 percent); reduction of physical fitness standards to “even the playing field” (70 percent); focusing on climate change as a top national security threat (70 percent); and critical race theory books appearing on the Chief of Naval Operations’ reading list (69 percent).

Most troubling for future recruiting is the survey finding that 68 percent of active-duty members indicate that politicization of the military impacts their decision to encourage their children to join the military.

Elected officials point at the military and tell them to do more to get recruitment numbers up. But the leaders in our country and communities should help, too. They could start by stressing the great package the military offers: Undersecretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness Gilbert Cisneros said to be “clear about what we offer: training, career mobility, and financial benefits in addition to community, connection, and a common purpose.”

One suggestion I found for the Navy could be applied to all the services: national and state leaders should help the service secretaries and the Secretary of Education work together “to create incentives for schools who have students who join” the military. Increased civics and history education would help combat apathy and inform more young Americans of why we defend our freedoms, helping them understand the importance of national defense.

And if political and public opinion leaders really want to help, they should take the standing of the military more seriously, rather than cave to self-serving special interest groups promoting policies – such as DEI initiatives – that sow division. The military’s recruitment crisis is a threat to national security. Our leaders should act accordingly.