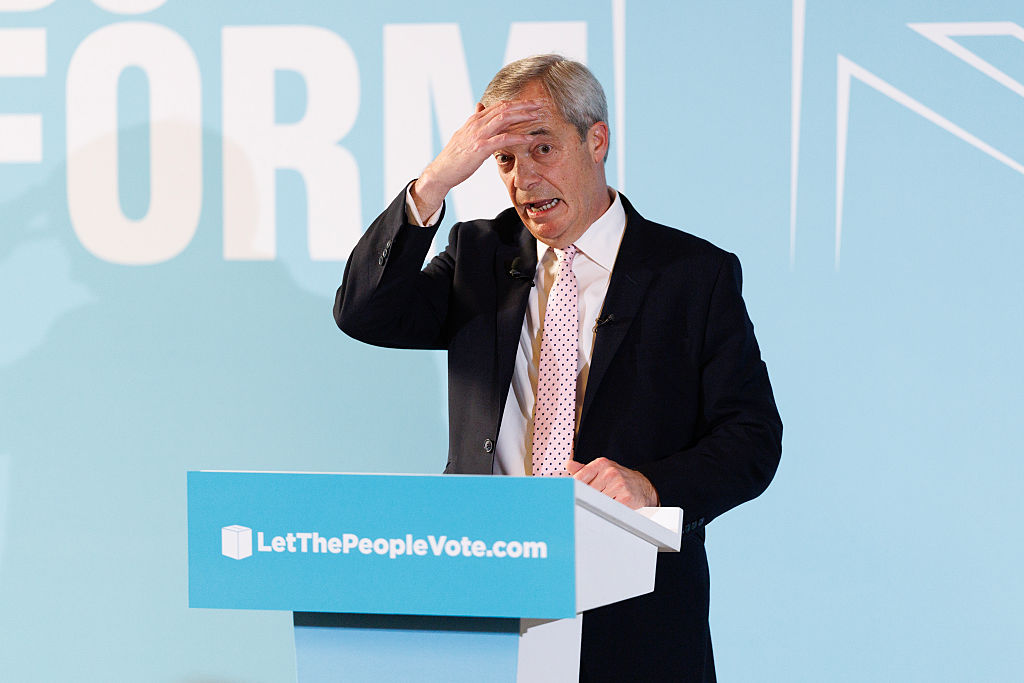

Boris Johnson’s first 100 days will make or break him — which is what makes his premiership unlike any other. In his favor is his ability to rally support in the country; against him the realities of a hung parliament.

How will he begin? It’s already clear that Boris Johnson intends to be an unconventional prime minister. His personality is such that he’s likely to eclipse all else in government. This is going to be the Boris Johnson show. Supporters and critics alike will be determined to keep him in the spotlight. He won’t change his style now that he has got the top job and privately, he is dismissive of those calling for a more somber — ‘statesmanlike’ — tone. Just as significantly, his No. 10 will be very different from that of his predecessors: he plans to staff Downing Street with veterans of the Vote Leave campaign and City Hall.

There is a strong Vote Leave streak running through his cabinet, too. Dominic Raab, a stalwart of that campaign, becomes foreign secretary and first secretary of state. Priti Patel, one of just a handful who sat around David Cameron’s cabinet table to support Leave, is home secretary. Michael Gove, who led the campaign with Boris, is now in charge of no-deal planning. The new chancellor, Sajid Javid, may have backed Remain in 2016 but he is more convinced than the institutional Treasury that the government can do things to offset the effects of no deal. Expect his Budget this autumn to be the most radical for many years.

This is not going to be a typical Westminster operation. But then, Boris’s was not a typical rise to power. Until now, almost every British prime minister climbed what Benjamin Disraeli famously called the ‘greasy pole’ that leads to No. 10 in the same way. They began with a stint as a backbench MP, served their time on the front bench, collected a tribe of fellow MPs — then gambled and plotted their way up to the party leadership.

Boris, however, has spoken from the despatch box less than any incoming prime minister in living memory, and yet he is as well-known as any of them. He is renowned as a rhetorician, a compelling public speaker, yet he has never made a memorable speech in the chamber of the House of Commons.

When he ran for mayor of London in 2008, many thought that was the end of his Westminster ambitions. George Osborne ribbed Boris about being a leading figure in municipal government while he, George, built up a formidable parliamentary operation. Now, more than a decade later, BJ is PM and Osborne is editing a municipal newspaper.

Boris will need the public to put pressure on parliament. This is why it’s worth keeping a close eye on how opinion polls react to his premiership. His speech from the steps of Downing Street on Wednesday afternoon was full of announcements designed to address the Tories’ electoral vulnerabilities. He pledged to start recruiting 20,000 more police officers immediately, to take action on social care and increase school funding. His cabinet looks like a team created with an election in mind; the technocrats have been replaced by those more comfortable on the television and the stump.

If it looks like Boris would win a majority in any election, parliamentary opposition to him will subside. And if that happens, then the EU will be far more likely to deal with him. Right now, many in Europe are convinced that parliament will stop no deal, so they see no need to make any concessions.

Boris is quite capable of mucking it up — even his closest friends agree. He has been a notoriously slow starter during his political career. Neither the early months of his mayoralty nor the first weeks of the referendum campaign went well. He takes time to accept what needs to be done. There have already been worrying signs of this tendency during the transition. He has avoided making definitive decisions on a whole host of issues. Partly this is temperamental: he has a journalist’s desire not to do anything until the deadline is upon him. (Even by journalists’ standards, he is hair-raisingly last minute.) And he hates being tied down to one source of advice.

When, at the end of last week, I asked one of his confidants how he was, the answer came back: ‘Feeling overwhelmed.’ His decision, however, to appoint Dominic Cummings to his Downing Street staff suggests that he has now decided on a course and will stick to it. Cummings’s appointment means Boris plans to get things done, even if that means upsetting the mandarinate. He knows that unconventional means got him to No. 10, and that the deck is too stacked against him to play the usual Westminster game.

The challenge for the new No. 10 team will be working within the current system. Without an election — and an election before Britain has legally left the EU would be extremely high-risk for the Tories — there’s no changing the parliamentary arithmetic. Boris will just have to find ways to get measures through this hung parliament, and to pacify those Tory MPs driven to distraction by his ascent who feel they have nothing left to lose.

There is just not time between now and October 31 to change how Whitehall works. His team — not Whitehall or parliamentary veterans — will have to learn how to get things done within these constraints. This puts a premium on ministers who know how to work the system, but there are only very few who can both do that and embrace the ‘do or die’ deadline of October 31. Tellingly, Boris has turned to Michael Gove to organize the government’s no-deal planning. Though Gove is the Tories’ most effective departmental minister, it had been thought that the issues between the two men would preclude him taking such a central role.

Boris’s decision to appoint Gove to the role is interesting for another reason – he has put someone worried about no deal in charge of preparing for it. This suggests that the new prime minister is acutely aware of how difficult no deal could be.

Brexit will be the defining issue. Failure to meet his deadline could destroy him (and his party). By contrast, if Boris can get a deal with the EU in time and secure parliament’s support for it, then he will be master of all he surveys. The question then will become when, not whether, he will call an early election. A majority will be his for the taking.

Within the Johnson camp, there is still debate about what the Brexit plan should be. Geoffrey Cox, the attorney general and one of Boris’s key early backers, thinks there are ways the backstop can be modified to ensure it is temporary: he regards this as the quickest way to a deal. But to his surprise (and that of many in the campaign) Boris ruled out that option in the final debate last week. This buoyed the faction around Iain Duncan Smith who want a standstill transition with the EU while a free trade deal is negotiated (described by Martin Howe QC on the page opposite). The EU, though, wouldn’t wear such a plan: it would be too much of a climbdown for the Irish and Brussels would want the European Court of Justice to have complete jurisdiction over any such arrangement.

I understand the proposal Boris Johnson intends to present to European leaders is neither the Cox plan nor the IDS one. ‘His idea is to seek a deal and prepare for no deal — that’s the strategy,’ says one key member of his team, before adding, intriguingly, that for this to work ‘both elements of the strategy must be credible’. In other words, both the no deal preparation and the proposed deal must be realistic. This is how best to understand the appointments of Cummings and of David Frost, a former EU director at the Foreign Office who was one of Boris’s special advisers when he was foreign secretary.

Cummings’ role will be to make sure that no deal is a logistically and politically credible option, Frost’s will be to ensure that the deal proposed is one that has a realistic chance of being agreed. To keep the Tory parliamentary coalition together both options need to be being taken seriously.

The EU’s initial instinct will almost certainly be to call Boris’s bluff. The broad EU view remains that either the UK parliament will stop no deal, or the Brits will blink when they peer over the cliff edge. But if the new government shows parliament cannot or will not stop a no-deal Brexit, the EU’s resolve will be tested. Leo Varadkar, the Taoiseach, will have to decide whether it is worth rigidly persisting with a backstop that is going to cause the very thing it was meant to avoid, a hard border on the island of Ireland.

There are plenty of Boris Johnson fans and plenty of enemies, but even the latter see an upside in him becoming prime minister. He’ll get his comeuppance now, they think. No one can deliver the impossible. But his critics might be surprised. If Boris Johnson is able to rally the country to this cause and change minds in parliament through pressure of public opinion, then all sorts of things become possible.

Since he was in tails, Boris Johnson has dreamed about what he would do if (as he once put it) the ball came loose from the back of the scrum. He now has the ball, and not much time to run with it. It is no exaggeration to say that the future of his party — and his country — depends on his success.

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.