A nonbinding, off-season ballot initiative in rural Oregon isn’t normally the most viscerally exciting of events, couched as they generally are in terms agonizing over whether to ‘note’ or ‘reaffirm’ a past proposal, or to ‘endorse’ or ‘refer’ a more recent one for further consideration. But just the other day, out of the tepid depths of yet more interminable debate on local timber-harvest regulations, or supplemental sport-fishing laws, something of genuine significance happened. The voters of five Oregon counties let it be known that they would like to secede from their state and join Idaho instead.

‘This election proves that rural Oregon wants out of Oregon,’ Mike McCarter, spokesman for the Greater Idaho movement, said in a statement. ‘If Oregon really believes in liberal values such as self-determination, the legislature won’t hold our counties captive against our will. If we’re allowed to vote for which government officials we want, we should be allowed to vote for which government we want as well.’

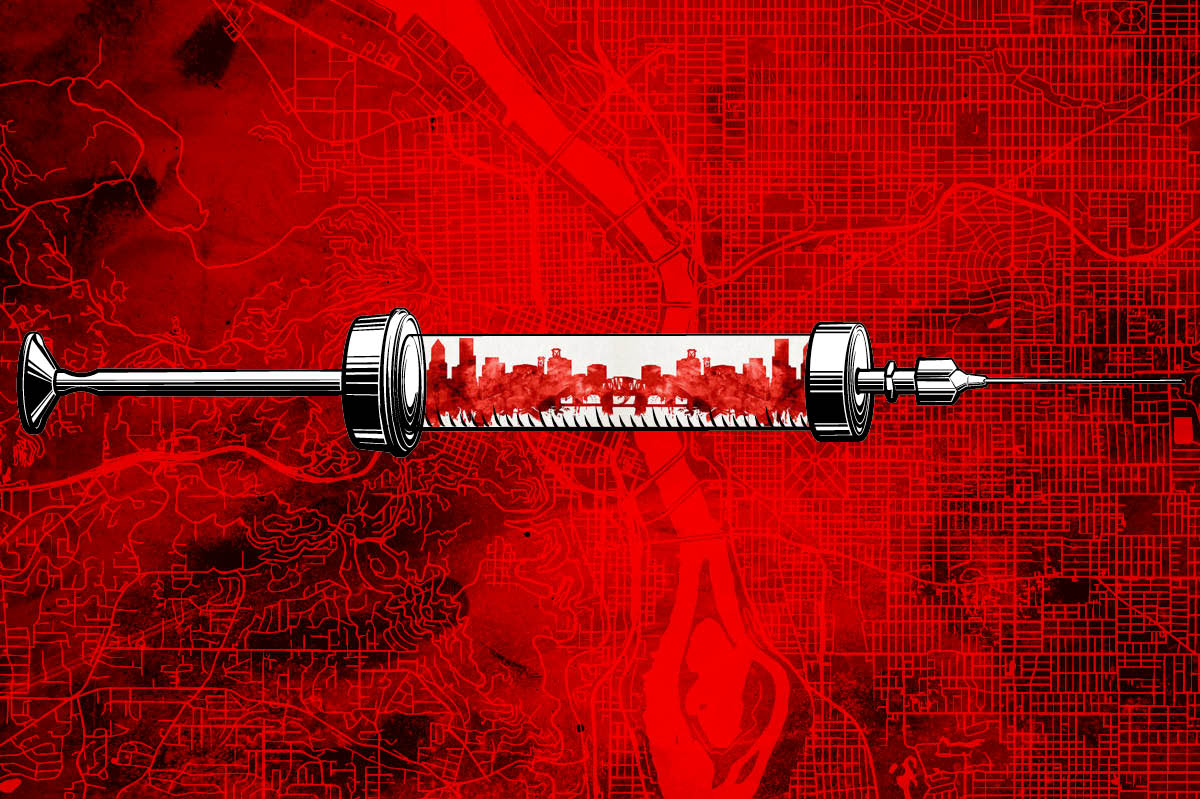

At this stage, the resolution only requires the commissioners of the five counties to continue to meet and discuss the proposal. The odds are still against anyone significantly redrawing the map of the Pacific Northwest anytime soon. But the disaffected voters of rural Oregon have history on their side when they complain about their treatment at the hands of the big-city slickers in Portland and elsewhere. Thomas Jefferson believed that a man shouldn’t be able to hear his neighbors’ dogs bark; he would have been horrified at the thought of people living quietly in the Oregon backwoods being bullied by the woke denizens of a state legislature hundreds of miles away. They also have momentum: two Oregon counties had previously signed up to the initiative and the Greater Idaho organizers are pushing to have 18 more counties vote on it in the fall. If things go the secessionists’ way, that would make a total of 25 counties ready to put the ‘gone’ in Oregon. There are only 36 counties in the state.

McCarter and his colleagues aren’t confining their Brexit moment just to rural Oregon, either. The master plan is to move Idaho’s border so that it encompasses more conservative counties in northern California and southeastern Washington — something that would create the nation’s physically third-largest state. Even the comedians at Saturday Night Live might have to consider taking Idaho seriously after that, as opposed to treating it as a running gag known for its potatoes and recurrent armed standoffs with the FBI.

It’s not difficult to see why so many people in Oregon might feel alienated from their political czars clustered together in the top-left corner of their state. I travel around the area pretty often and you can’t help but notice something. Oregon is really two states. Obscured within the one, administered by an exclusively Democratic legislature for the convenience of the social-justice warriors who live in greater Portland or college towns like Eugene and Corvalis, lurks a vast hinterland withering in its neglect, left behind by the second half of the 20th century. If you want a snapshot of the political Grand Canyon that runs through Oregon today, you need only look at the results of last November’s presidential election. In metropolitan Multnomah County, which includes Portland, Biden won by 79.8 percent. About 270 miles southeast in Grant County, where they used to profitably pan for gold until the federal government outlawed it in 1942, they went for Trump by 77.5 percent . Aside from being part of the same consolidated Territory admitted to the Union in February 1859, these two enclaves would seem to have little in common, which leads McCarter to ask wistfully, ‘I wonder whether loud, big-city Oregon will ever care about quiet, small-town Oregon?’ He fears not.

If you drive west from Portland and then head down the Pacific coast, as I did the other day, you get some of the flavor of the issue. Behind you is the moronic inferno of America’s so-called Rose City, where lots of people have tattoos and piercings, the general state of municipal repair is akin to Dresden in 1945 and a Republican has about as much chance of being elected to public office as I do of becoming the Super Bowl’s next MVP. Ahead lies a long chain of bucolic hamlets populated by friendly, well-dressed men and women in essence unchanged from the time of Ike in the White House and Dean Martin slurring his way through ‘That’s Amore’ on the radiogram. It’s as though the whole area has somehow managed to slip through a crack in the space-time continuum, to lie not so much indifferent as oblivious to the march of progress. You see long rows of neat, clapboard houses, many with a US flag fluttering out front, and spruce little towns with names like Rockaway Beach, Seaside, Tillamook and Wheeler.

Wheeler! Even to write the word is to be reminded with a jolt of the two warring Oregons. In fact the 400-strong ‘city’ of Wheeler might be said to embody the great divide. Today it’s a sleepy place with a few unostentatious wooden shacks and equally modest stores set on a grassy slope rising up from the banks of the Nehalem river. A century ago it was a logging boomtown, where some shopkeepers still took their payment in gold, women in tight skirts loitered in doorways on Hemlock Street and lumberjacks drank and gambled away the afternoon. The big man in town was a sawmill operator and philanthropist called Coleman Wheeler, and he eventually gave his name to the place. Coleman’s great-grandson is ‘Tear Gas Ted’ Wheeler, the mayor of Portland, who spent much of last summer not just mouthing the latest BLM slogans but actually manning the barricades, standing on the downtown courthouse steps to express solidarity with the rioters busy torching his city and berating the federal agents sent to restore order. A case could even be made for saying you can trace the decline in public life in Oregon by the quality of the Wheeler family: from civic-minded entrepreneur to megaphone-wielding loudmouth in just three generations.

‘The consternation that has come upon us is the result of a sectional election of a president, whose opinions and avowed principles are in antagonism to our interests and rights, and we believe, if carried out, would subvert the Constitution under which we now live.’ The Georgia assemblyman Alexander H. Stephens said this in the course of a speech on the secession issue in 1860. You could add ‘and government at every level’ after the word ‘president’ and have a pretty good idea of the political unrest now sweeping through the Pacific Northwest like a slow-burning but relentless summer wildfire.