One hundred and twenty minutes. That’s how much time more than 40 percent of American children spent on TikTok every day last year. The app, owned by the Chinese company ByteDance, worms its way into the minds of young people to an extraordinary degree, dwarfing their use of Instagram, Facebook, Twitter/X and Snapchat. And when word went out that the House of Representatives was seriously considering forcing a sale to peel the app away from the power of the Chinese Communist Party, TikTok fired back by weaponizing the same children against Congress — driving a deluge of confused phone calls to Capitol Hill, including some where teens threatened to commit suicide if the vote went forward.

To its rare credit, the House of Representatives ignored the propaganda and voted in an overwhelming bipartisan fashion against TikTok, advancing a bill that would force some large social media companies owned by America’s foes — China, Russia, North Korea and Iran — to divest, find new ownership or lose app store availability within 180 days. The howls of the manipulated younglings were not enough to put members off this idea — they may even have hastened the vote. Congressmen do not take kindly to such manipulated caterwauling, particularly from those who can’t even vote yet.

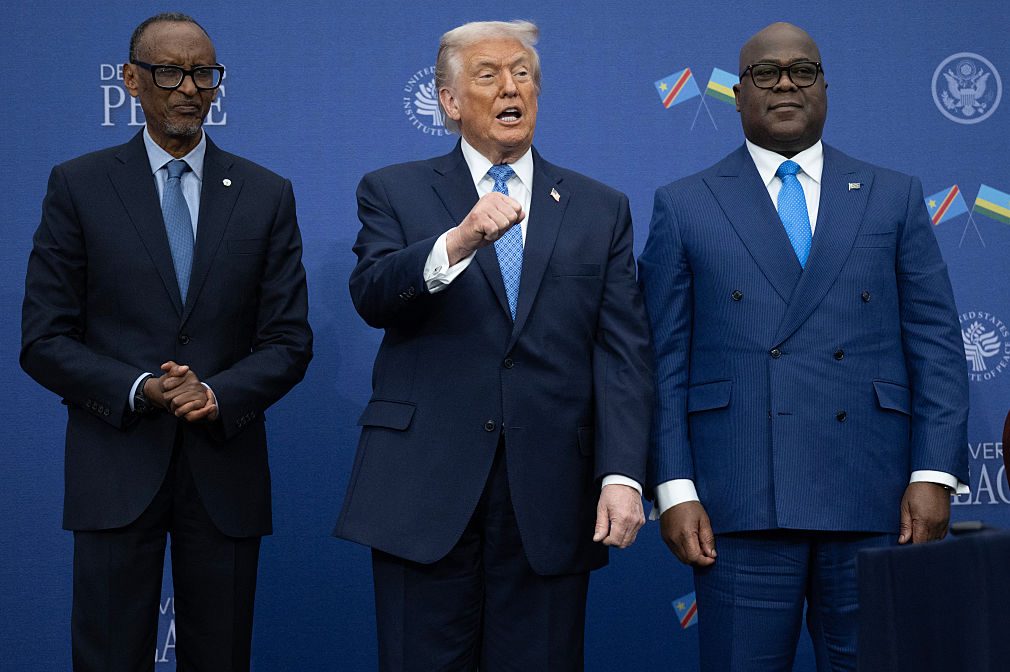

At this writing, the matter is before the US Senate, where Big Tech has typically found that its lobbying dollars go farther and faster than they do in the more populist House. But the turn against TikTok is surprising, a moment of bipartisan unity in an election year, no less. Donald Trump was briefly opposed to the idea, manipulated by his former campaign manager Kellyanne Conway (who signed up for the Chinese dollars), who embraced the libertarian free speech arguments of Rand Paul and Thomas Massie as a mangled defense of the CCP’s mind virus app. But he came around almost immediately when it became clear his old pal Steve Mnuchin would be the potential beneficiary of a forced sale.

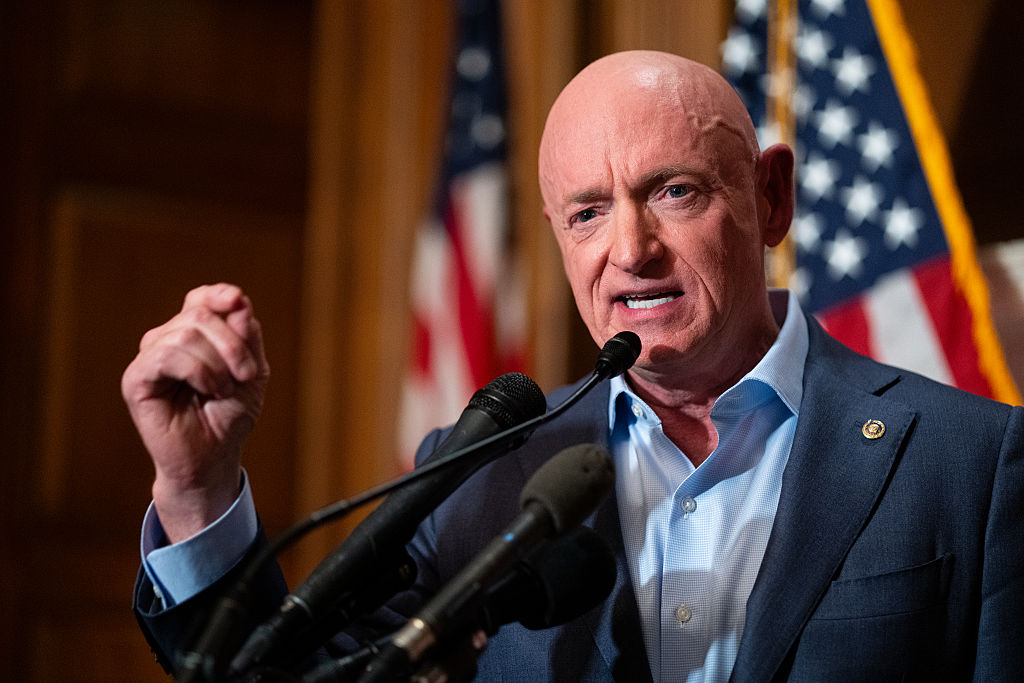

With Joe Biden, the track was more complex. Democrats view TikTok as a potential third rail, possibly hurting them with young voters in the fall. They were skeptical enough that powerful senator Mark Warner’s approach to nixing the app went down to ignominious defeat last spring.

“All the momentum died, notwithstanding the fact that we were building the evidentiary case against ByteDance’s control of TikTok, because people were gun-shy after [Warner’s] act failed,” Select Committee on China chairman Mike Gallagher told me. “And you had signals from the White House, from major officials saying ‘hey, you know, we don’t want to anger antisemitic eighteen-year-olds in a campaign season.’ They didn’t say that outright, but you get the idea. And then the Biden campaign joined TikTok, so you could read the room.”

So what changed? The answer is simple: October 7. Suddenly Democratic congressional offices were deluged with anti-Israel propaganda, fueled and reinforced by TikTok videos served up to easily manipulated tweens and teens. Well, that’s enough of that, Democrats said internally — and rebooted the conversation with Republicans, key among them Gallagher, the focal point of the Congressional anti-China effort. After the horrific Hamas assault on Israel, Gallagher was approached by one Democratic colleague after another, all saying something had to be done about TikTok. The data were clear — the committee had the metrics to compare hashtag trends on certain topics across social media networks, and they showed a startling flood of pro-Hamas material on TikTok, revealing disparities that wouldn’t have been present unless their algorithms were being manipulated by a foreign power.

“All of these things conspired to breathe new life into our effort,” Gallagher said. Congress needed a bill that would thread the needle, satisfying concerns on the right about granting the executive branch more power while withstanding serious scrutiny from First Amendment advocates and an inevitable legal challenge from ByteDance. Gallagher believes they got it. He credits members as far apart politically as Nancy Pelosi and Steve Scalise for the overwhelming 352-65 vote where even age wasn’t a divide — 78 percent of the 124 members under the age of fifty voted in favor.

The arguments in favor of ridding America of TikTok in its present form often sound like arguments against smoking, marijuana or drinking, but the reality is that the danger of its mind-altering effects is far more immediate than those of nicotine, drugs and alcohol. Alleigh Marré of the American Parents Coalition tabulates the data in devastating detail — exposure to suggestions of suicide and self-harm and patterns of depression-fueled loneliness are shocking.

“The algorithm feeding them content that the CCP deems appropriate is a unique set of consequences and dangers, and a lot of the time when parents are thinking of parental controls through the lens of the social media we’re familiar with — Instagram, Facebook, Twitter — [they’re not thinking] along the lines of this new experience, which is totally different,” Marré says. “There are problems there, but TikTok’s problems are very unique.”

Marré points to examples that are absolutely terrifying if you have young children: videos that illustrate how to experiment with self-harm and tips for hiding dangerous behavior from your parents, advice on how to get around parental consent laws and keep your web explorations secret, and material sending young kids — particularly girls — down eating-disorder rabbit holes.

“There’s a difference between free speech and an algorithm, and who controls that algorithm today is a known adversary bent on undermining us,” Marré says.

The needle threaded in the House legislation may prove to be enough for the Senate. Yet for some China hawks, the TikTok move is the lowest-hanging fruit — and if it’s all the Select Committee has as its legacy, it’s a sad commentary on a Washington where bipartisan unity against Red China may be less strong than politicians would like to pretend.

“My view is that we are in the window of danger with China where they could move,” Elbridge Colby, author, foreign policy expert, and the rare bon vivant of this depressed moment, tells me. “Yes, maybe it could be 2027. But it also could be tomorrow.”

To Colby, the TikTok legislation is an anti-propaganda sideshow that doesn’t really address the real problems of hemming in an increasingly militarized CCP.

“We’re behind the curve militarily, and what matters the most for whether or not Xi Jinping is going to move, in my view, is the military balance, and whether there are credible reasons for his constraint,” Colby tells me. “Xi’s continuing to build up his military; he’s sanction-proofing the economy in the face of headwinds. I don’t think economic sanctions work in this world — they don’t even work in North Korea and Cuba. They’re not even working that well to hinder Russia’s defense-industry recapitalization. Xi Jinping is telling Biden directly that we are strangling them… China’s saying, ‘We believe you’re trying to strangle us from the global economy and restrain future growth.’ They have a military instrument to try to break out of that coil like the Japanese tried in 1941. And so we should ‘speak softly and carry a big stick.’ Have a shield that says to China, ‘it’s just never your day to roll the dice’ — but at the same time, I also want them to think that there’s a plausible option for them with peace.”

That’s the potential downside of Congress’s TikTok move. But the upside is considerable, too. Matthew Yglesias and Derek Thompson, two neoliberal thinkers who have generally come down on the anti-TikTok side of the equation, propose a hypothetical: imagine a world in the middle of the Cold War, where the Soviet Union or a business it secretly funded sought to buy CBS. The very effort would be laughable — the United States would never have allowed a foreign adversary such power. Yet with TikTok, we have an even more powerful and pervasive entity than any major network, with the ability to steal our data (it does), spy on us (it has) and manipulate our thoughts and the thoughts of our children (it seeks to do so, daily). Why allow such an entity to persist, a mind-flayer of international proportions, when it has no right to do business here absent the permission of our government?

Yet as much as the TikTok legislation has been a rare moment of ideological unity, it is only a facade, suggesting there is strong bipartisan unity on China when there is not. The Select Committee is an investment of political capital — and its work has led to an escalation of the issue. Without a dramatic upgrade of the American military, and of its allies in the Asian rim, a TikTok pushback is small potatoes. It’s a tech hiccup, a shiny object — when we need a message of resolve backed by military might.

It has, however, been a revelatory moment for some of the resolute China hawks on the right: they now have a clearer idea of who is not on their side. A loud but ultimately irrelevant contingent of populist gadflies — whether motivated by dollars or nonsense — took to defending TikTok in a way that left many China critics scratching their heads.

“I have a lot of problems with our government, but I think it’s a lot better than the Chinese Communist Party,” Colby says. “I’m also like, ‘wow, people are this spiritless and cynical?’ I mean, the government that we operate under has not caused millions to starve, [perpetrated a] Cultural Revolution in living memory, [or] the genocide of Uighurs… it seems to me that as a conservative, it’s always good to remember things can get a lot worse.”

Some who worked on the legislation dismiss arguments against the TikTok bill as bought and paid for — likely by Jeff Yass, the top Republican donor of the moment and a billionaire who happens to have a lot of money tied up in ByteDance. Yass is a major funder of the Club for Growth, which put them in the awkward position of announcing that a politician’s vote for the TikTok bill would reduce their “score” as a conservative. They claim the TikTok bill proposes some type of triple bankshot an administration could use to shut down Twitter/X or some random person’s small-business website. Try as I might, I could not find a single prominent conservative or libertarian attorney who took this possibility seriously, given the narrow frame of the legislation.

It seems far more likely that what’s behind any opposition to it is the wave of anti-Americanism that has swept over some populists in recent years — motivated in part by frustration over Donald Trump’s 2020 loss, and in part by belief that America is some vast secular force for ill around the world. Their laments ultimately sound more like the arguments of Black Lives Matter than something from God and Man at Yale — and their anti-Reaganism seems to have extended into outright rejection of the City on the Hill. For them, the Constitution is a ruined bit of enlightenment hangover, and the Founders were too feckless with their plans for the future. It brings to mind a speech of Daniel Patrick Moynihan on the floor of the United Nations:

Am I embarrassed to speak for a less than perfect democracy? Not one bit. Find me a better one. Do I suppose there are societies which are free of sin? No, I don’t. Do I think ours is on balance incomparably the most hopeful set of human relations the world has? I mean by ours those two-dozen-odd democracies of the world. Yes, I do. Have we done obscene things? Yes, we have. How did our people learn about them? They learned about them on television, in the newspapers.

The TikTok divestment, if forced, would be a powerful message about setting limits to the ability of America’s foes to recruit within the ranks of our citizenry. That it happens to be a bipartisan step is all the better.

“Doing nothing is not an option,” Gallagher tells me. “My biggest intellectual evolution is that I conceived of the competition with China in purely military or economic terms for the last fifteen or so years. But I’ve come to appreciate the ideological dimension. They’re trying to weaken us from within, intensify narratives of self-loathing in America, to reduce any moral authority. So we have to challenge them. And I think, in light of that, in light of Xi’s efforts in the smokeless battlefield, the idea is simple: that we don’t allow the dominant news platform for young Americans to be controlled by our foremost adversary, one that is waging ideological warfare against us right now, that we defend ourselves from a country that is trying to just destroy American global leadership and pit Americans against Americans.”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s May 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply