Does Facebook hold the key to bringing the perpetrators of the Rohingya genocide to justice? Four in 10 people in Burma use Facebook. Among them was the omnipotent commander-in-chief of the country’s armed forces Min Aung Hlaing, before he was banned from using the platform in 2018.

Now Gambia, backed by the Organization of Islamic Countries, has initiated court proceedings in the United States to compel Facebook to release data on ‘suspended or terminated’ accounts of General Min and other of Burma’s military top-brass. They hope this will yield vital evidence that can be used in the International Court of Justice (ICJ) at the Hague to prove that Burma is guilty of horrific crimes against the Rohingyas. This month, Britain imposed sanctions on two high-ranking Burmese generals, who were allegedly ‘involved in the systematic and brutal violence against the Rohingya people’.

The nature of the deadly crackdown in Burma has made obtaining evidence a difficult task. But disclosure by Facebook could be a key moment in the quest to find and punish the perpetrators of this crime. In January, Gambia obtained an interim ruling from the ICJ, ordering Burma to take ‘all measures within its power’ to prevent genocide against Rohingyas, who have suffered persecution ever since Burma became independent from Britain in 1948.

At the ICJ hearing, Burma’s de facto prime minister, the once revered but now reviled Aung San Suu Kyi, maintained that no state violence had been committed against Rohingyas. Instead she suggested the conflict had been instigated by a sectarian insurgency and described what has been unfolding in Burma as an ‘internal armed conflict’. Seventeen judges from as many countries unanimously rejected this and ordered Burma to protect the Rohingyas. But for now, the judgement means little; the ICJ has no way of enforcing it.

When George Orwell worked as a police officer in the South-East Asian country, he perhaps unwittingly revealed the way the Rohingya people are viewed by many Burmese. ‘In Moulmein, in Lower Burma,’ he wrote, ‘I was hated by large numbers of people — the only time in my life that I have been important enough for this to happen to me.’ The loathing that he as an imperialist received from Burmese Buddhists — who make up over 80 percent of the country’s population — is a prejudice exuded in far greater measure towards Rohingya Muslims.

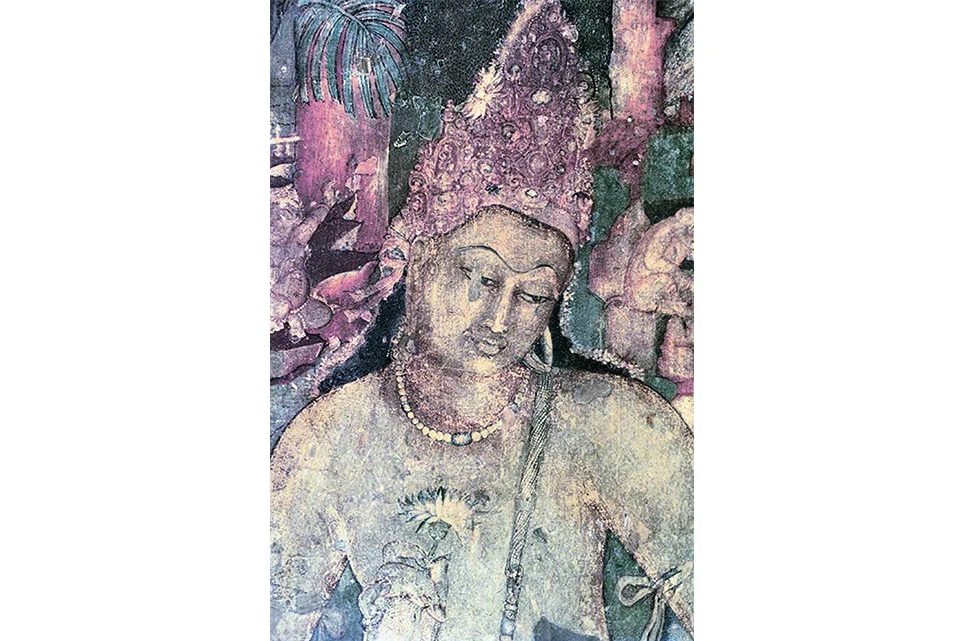

Muslim settlements in Arakan State (renamed Rakhine State), where Rohingyas are concentrated, can be traced back to the 1430s, before the Burmese empire annexed it in 1784. Burma in turn was seized by Britain in 1824 and remained under its tutelage as part of British India. During this period more Muslims from neighboring south-eastern Bengal moved to Burma as migrant workers. After being freed from British rule, the Burmese administration blackballed Rohingyas from its constitution.

When Burma’s military dictatorship grabbed governance in 1962, state-sponsored persecution of Rohingyas intensified, culminating in them being singled out as non-citizens in 1982. In short, Rohingyas are stateless and branded by Burma as illegal immigrants from Bangladesh; although the latter country only came into being in 1971.

The massacre began in 2017, when Rohingya militants attacked police posts. This provoked a ferocious military backlash, which the United Nations said amounted to ‘ethnic cleansing’. In those clashes, Medecins Sans Frontieres estimated that at least 6,700 Rohingyas were killed, including 730 children under the age of five. The government admitted 400 died in ‘clearance operations’ against militants. Yet analysis of satellite imagery by Human Rights Watch appeared to show that at least 288 villages were partly or wholly razed to the ground.

This evidence seems to be compelling, but more is needed. If proof of genocidal intent is found in exchanges on Facebook or Messenger, then anyone accused of involvement in the terrible scenes that unfolded in Rakhine State can be tried in the International Criminal Court (ICC) at the Hague. Burma does not recognize this body, but Bangladesh does. As Burma’s western neighbor, it has received the brunt of the 700,000 fleeing Rohingya refugees. The ICC asserts that since Bangladesh is a member and an affected party, which also supported Gambia at the ICJ, the ICC has authority to hold a trial. This, though, is dependent on approval by the UN security council, where China and Russia could throw a spanner in the works.

[special_offer]

After more than half a century of martial law — often brutally administered — Burmese generals now share power with a civilian partner. In effect, Suu Kyi is in office, but not consummately in power. Three key portfolios in her cabinet — defense, home and border affairs — continue to be monopolized by the military. If she ventures into a fight for Rohingyas’ rights, she would be vulnerable to eviction by both the military and the predominantly Burman electorate, who will exercise their franchise later this year.

Suu Kyi cannot be condoned, however, in any way for her apathy towards the Rohingya. Her fall from grace is spectacular. A daughter of the assassinated Burmese independence hero Gen. Aung San, she seems to have longed to inherit his legacy, rather than introduce liberty to her nation.

The treatment of Rohingyas has been a malfeasance of extraordinary magnitude. But now, there is at least a glimmer of hope of justice for victims of this cruel genocide.

This article was originally published onThe Spectator’s UK website.