Francis Collins, then head of the powerful National Institutes of Health, got right to the point.

In a closed-door meeting with pharmaceutical manufacturer Edwin Thompson, Collins demanded Thompson back off his campaign to drastically cut back the use of prescription opioids for chronic, long-term pain.

According to Thompson, Collins admitted healthcare regulators knew there was no science showing opioids were effective for anything but acute, short-term incidents. There was at the same time credible research showing the longer a patient remained on opioids, the greater the risk of addiction. Some studies even suggested long-term use increased pain sensitivity.

But on that day in 2019, none of that mattered to Collins. If Thompson persisted in blaming federal health and law enforcement officials for skyrocketing addiction rates, Collins implied the government would come after him.

“You need to change your attitude, you need to approach this differently,” Collins said, according to notes of the meeting at an Atlanta conference on the opioid epidemic, taken by Thompson’s two sons. “You need to give the FDA a solution, not threaten them.”

Then, as if the point weren’t entirely clear, he added, “You better watch yourself.” Collins complained of Thompson, “You want blood and are confrontational.”

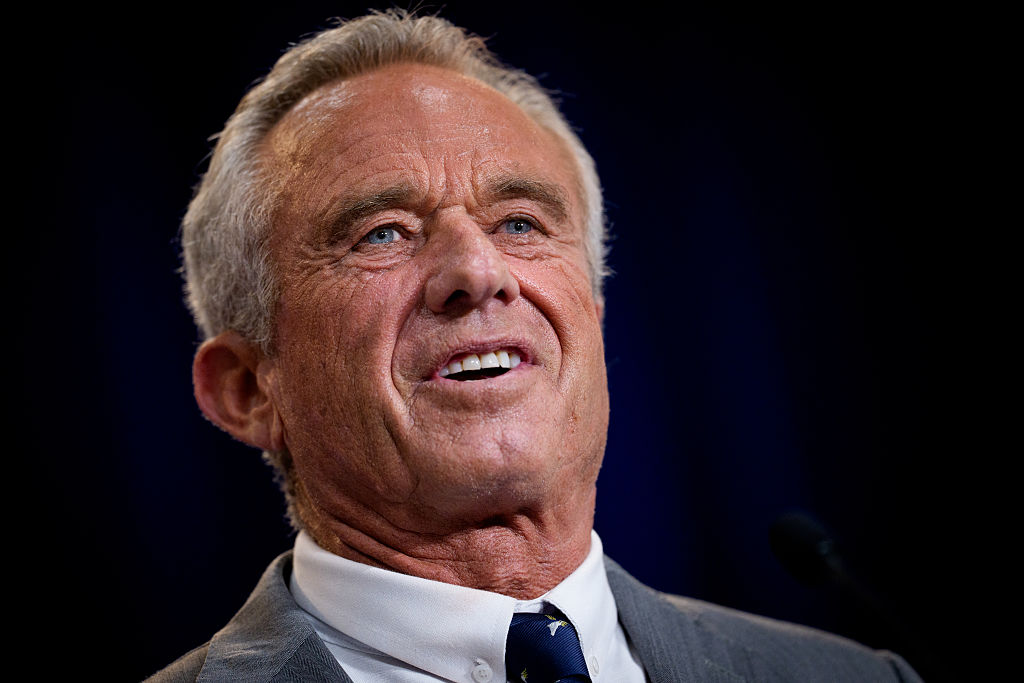

Collins, you may recall, is the public health bully who attacked the authors of the Great Barrington Declaration urging caution on Covid lockdowns and school closings, a document that turned out to be prescient in its assessment of the harms to school students, the economy and public health overall. Collins called the since-vindicated declaration authors “fringe epidemiologists,” which, for a scientist, was a surprisingly nasty ad hominem attack. He also asked Anthony Fauci for help drafting a “devastating” op-ed denouncing them.

He tried a similar tactic on Thompson. It didn’t work.

“I expected to have a robust scientific conversation with this guy,” Thompson said in an interview in the spare, modernist office building that serves as his headquarters. “There was not one moment of scientific conversation.”

In the extraordinarily lucrative and opaque world of Big Pharma, Thompson is an anomaly. He is a contract pharmaceutical maker who has become fabulously wealthy making drugs for the biggest pharmaceutical makers on the planet. Thus he has a lot to lose by pointing his finger at healthcare regulators such as Collins who decide whether he can sell his drugs and on what terms.

He refuses to discuss his net worth, but he travels by private jet, drives a Rolls-Royce to the office and owns a sprawling horse country farm just outside Philadelphia. His privately held company, PMRS Pharmaceuticals, operates a state-of-the-art manufacturing and research facility whose estimated replacement value is well north of $100 million.

Most of his clients insist on confidentiality, so Thompson declined to disclose drugs manufactured by PMRS. But he says the company makes many commonly used prescription medications.

One exception to the typical confidentiality arrangement was Opana, a powerful prescription opioid made by Thompson’s company. Endo, the patent holder, listed PMRS as the maker on the drug label. In 2017, the FDA ordered the removal of the drug from the market following outbreaks of HIV and Hepatitis C among illicit users who injected the drug. Endo is now in Chapter 11, the target of lawsuits alleging it foisted dangerous opioids on the public.

What makes Thompson important is his authority as a drug maker, the cogency of his analysis and his utter fearlessness in exposing industry and regulatory abuses.

Thompson has spent the better part of the past six years castigating industry peers and regulators for not only causing the epidemic but failing to take steps he says would quickly halt its advance. He’s spent millions on a lawsuit trying to force the FDA to change its opioid policies, testified at FDA advisory committee hearings and advised members of Congress. Thompson’s core argument is that while health care regulators have dialed back the use of prescription opioids, they are still far more widely used than at the start of the epidemic in 1995.

And still doing great harm. Today, even after alarms have been raised, the United States accounts for 80 percent of the world’s consumption of prescription opioids.

This is because the FDA and many American physicians continue to endorse the use of opioids for chronic pain treatment. This policy remains in place despite multiple studies showing opioids’ long-term use greatly increases the risk of addiction and death and that their pain fighting attributes diminish over time. Drug companies and physicians who continue to prescribe opioids long-term say that for some patients there isn’t anything else that works.

Two CDC physicians, Thomas Frieden and Debra Houry, did the seminal study on this subject and they, like Thompson, argued for steep cuts when the results were released in 2016. Twenty-six percent of persons undergoing long-term treatment became addicted, they found. One in thirty chronic pain patients treated with the highest doses could expect to die two and a half years from the onset of treatment.

“We know of no other medication routinely used for a non-fatal condition that kills patients so frequently,” they wrote in the New England Journal of Medicine.

***

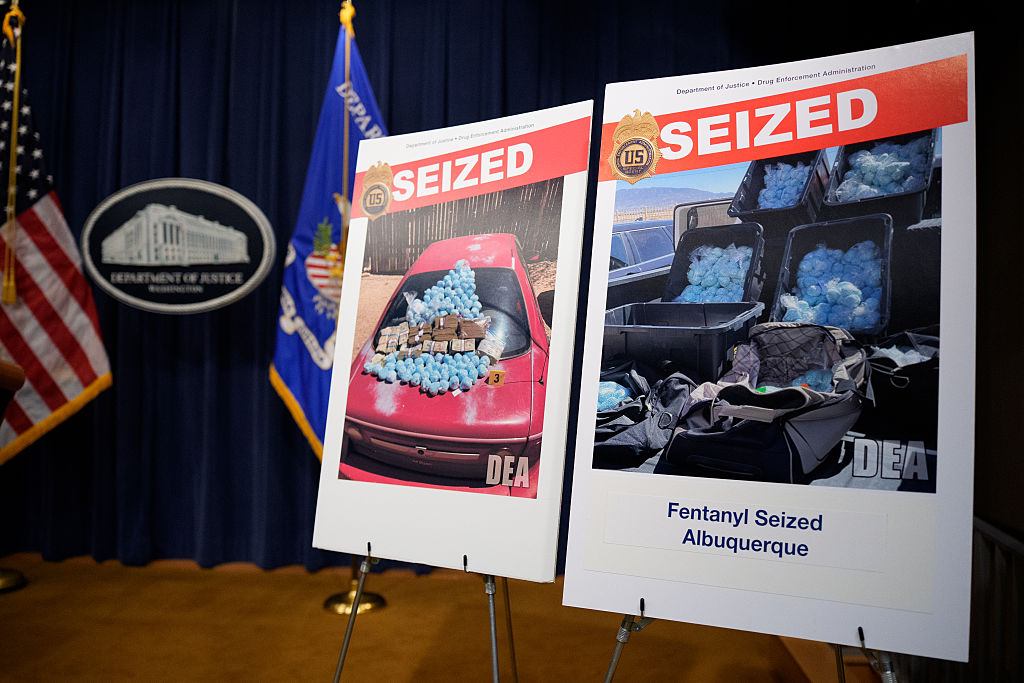

While the synthetic opioid fentanyl now is responsible for a major share of overdose deaths, Thompson argues that new addicts are created every day by drug companies and physicians who use prescription opioids unnecessarily for chronic pain treatment. Many of these people eventually move on to street drugs like fentanyl. He has no quarrel with the use of opioids for the short-term treatment of acute pain. When prescribed for a short duration of a few days, the risk of addiction is low.

“There is overwhelming value in using opioids for acute, short-term pain,” he said. The problem is that most prescriptions are for long-term treatment, with its higher risk of addiction and overdose. “Until we get back to ’95 levels, we are still going to have an epidemic.”

Much of what Thompson says about the opioid epidemic seems incontrovertible. Perhaps that explains Collins’s overwrought reaction.

Every year, when the federal Drug Enforcement Agency issues opioid manufacturing quotas, Thompson distributes an updated bar chart showing the trend lines. He is a great believer in the power of a simple chart to communicate transformational ideas, and a framed copy of Louis Minard’s graphic depiction of Napoleon’s catastrophic retreat from Moscow in the winter of 1812 hangs on the wall behind his desk.

Like Minard’s, Thompson’s chart tells a simple but devastating story.

At the start of the epidemic in 1995, opioids were largely used for the treatment of acute short-term pain at much lower dosages — 5mg was the norm, as against 50mg and above once the epidemic got underway. The production quotas for oxycodone, a powerful semi-synthetic that is the most prescribed opioid, stood then at 5,000kg.

Fifteen years later, after the FDA had approved a half dozen prescription opioids for the treatment of long-term chronic pain, that number had spiked to 120,000 kg. While the DEA began dialing back the quotas in 2016, and physicians became far more wary in prescribing opioids following a tightening of the guidelines by the federal Centers for Disease Control, Thompson points out that oxycodone allocations are still nearly a dozen times what they were at the start of the epidemic.

Why this is important was made clear in a study by NIH deputy director Wilson Compton, deputy director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, who found in 2014 that up to 80 percent of heroin users had first used prescription opioids.

One of the more salient aspects of the deepening opioid crisis is that drug makers, the people most responsible for unleashing this scourge, have been almost entirely silent on the industry’s role. There’s been no soul searching, no wringing of hands, and no anguished postmortems on how it all might have been avoided.

In the drug industry, Thompson is the lone exception.

His story is little known. After a twelve-minute segment on 60 Minutes a few years ago, he has received no press attention. He grew up in a row house in a tough neighborhood in Camden, New Jersey, and did so poorly in high school that the only college that would admit him was a two-year community college. He seems to have been a bit of a rabble rouser as a youth and some of that bravado remains. Thompson said that during his meeting with Collins, he pushed back hard as soon as it was clear Collins intended to pressure him.

“I got right up into his face and said ‘if you think you are going to threaten me, you haven’t done your homework.’”

Collins did not respond to requests for comment on this article.

***

After his fumbling start in high school, Thompson says he soon learned self-discipline and finished his undergraduate work at a four-year teachers’ college. He credits his family and a salutary, if halting, maturation for the turnaround.

It was no one thing that did it. Just a slow process of growing up.

“We all mature, don’t we? I would love to tell you that there is an inflection point in life,” he said. “I had plenty of opportunities to get self-discipline earlier. I call it getting on the train. Most of us get on the train. Not at the same time. And when you get on the train you get this figured out.”

After his undergraduate work, Thompson went on for graduate training in physiology at Fairleigh Dickinson University and from there took an entry level job as a pharmaceutical salesman for Johnson & Johnson.

At J&J, one of his first assignments was promoting the company’s new anesthesia drug, fentanyl.

Known largely to the public as the latest scourge of the opioid epidemic, fentanyl was then seen as a breakthrough anesthesia drug because it was more easily controlled than the commonly used anesthetic gases, ether and nitrous oxide. Fentanyl gave surgeons more flexibility — its effects were more easily monitored; they could keep patients on anesthesia longer if needed and complications declined. It is still widely used for general surgery and Thompson ruefully remarks that one of the bitter ironies of the opioid epidemic is that a drug that improved surgical outcomes is now responsible for tens of thousands of overdose deaths.

Thompson left J&J in 1986 to become CEO of Greenwich Pharmaceuticals, a small drug maker that focused on arthritis remedies and other autoimmune diseases. He went out on his own in 1994, founding PMRS Pharmaceuticals, his contract pharmaceutical manufacturing company.

His position on opioids evolved over time, but he says he first became alarmed in late 2013 while making Opana.

Endo had claimed that Opana was a supposedly abuse-resistant pain medication formulated so that it couldn’t be crushed or pulverized and then inhaled or injected. The FDA had encouraged this approach for opioid makers, saying it would go a long way to halting the illicit use of prescription opioids.

But it turned out that the Opana formulation was easily compromised.

During a routine test of a production batch, Thompson noticed one of his staff scientists cutting up a tablet with a pair of scissors. He realized in an instant the tablets, once sliced open, would be water-soluble and thus injectable.

“That’s when the light went on. I said, ‘Oh, no’,” he recalled. “The moment you give me some surface area, the narcotic immediately rolls out into the water.”

He tried to alert the DEA and the FDA, not just about Opana, but other opioids such as OxyContin, which used the same abuse resistant formulations, but they dismissed his concerns. Frustrated by the lack of an official response, he filed a so-called citizens petition with the FDA, asking the to agency amend drug labels disclosing that abuse deterrent formulations could be easily reversed.

But he got no response.

Because of his status as both an industry insider and outspoken critic of US policy on opioids, members of Congress regularly turn to Thompson for advice on how to rein in drug makers and the FDA.

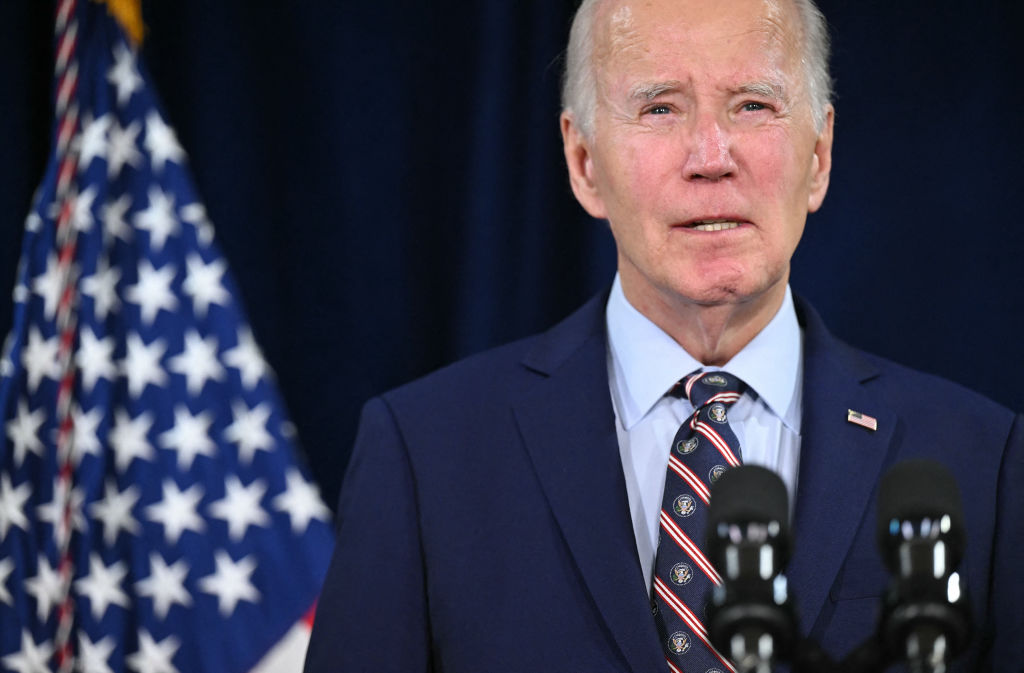

In 2021, when Senators Maggie Hassan and Edward Markey moved to block the Biden administration from nominating longtime FDA senior official Janet Woodcock as FDA commissioner, they drew in part on advice that Thompson had given them on Woodcock and the inner workings of the FDA. Thompson had earlier briefed Hassan on how the FDA’s sign-off on the use of opioids for chronic pain had triggered the epidemic, essentially opening a Pandora’s box, and how supposed abuse deterrent formulations did little to stop recreational drug users. He argued they were little more than an industry fig leaf designed to camouflage the dangers.

Thompson made the same arguments at multiple FDA advisory committee hearings and symposia on the epidemic.

In her longtime FDA role, Woodcock had given approvals for a half dozen or more prescription opioids, including OxyContin, the notorious extended-release opioid that cut a wide swath of death and destruction.

Favored by the drug industry, Woodcock was deemed early on as likely to take over as head of the agency after the 2020 presidential election, but the Biden administration never moved forward with the nomination after Hassan and Markey raised objections.

The gambit that seems to have triggered Collins’s ire was a lawsuit that Thompson filed against the FDA in 2019 challenging the agency’s rejection of his application to market a 5mg opioid capsule for the treatment for acute short-term pain.

Under normal circumstances, Thompson could have expected the FDA to give its go-ahead.

But Thompson included a provocation in his request for approval.

He not only asked for permission to market the drug but proposed including a statement on the package label saying the drug could be used only for treatment of acute, short-term pain because there is “no evidence of efficacy” for the use of opioids for chronic pain. For good measure, his proposed label also stated abuse-deterrent formulations are ineffective.

In truth, Thompson said he never intended to produce and market the drug. If the FDA had granted approval with his proposed package label, Thompson said he would have sent a mass mailing to primary care physicians around the country noting the FDA was on record saying opioids were of no value in the treatment of chronic pain.

Initially, the FDA scheduled an advisory committee hearing on the application, normally a key step toward approval. But then the agency abruptly canceled the meeting and denied the application.

Apparently the FDA had caught on.

Thompson appealed the decision to the US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, which ruled against him, agreeing with the FDA that Thompson’s application had failed to include a workable plan to prevent abuse.

Yet Thompson says he is undeterred, and plans to continue his advocacy.

“I am waiting for someone to come up with data showing me that I am incorrect,” Thompson said. “But we don’t have it. The FDA got it wrong and they’ve refused to admit their mistake. The real cause of this was the original (chronic) labeling. This is a government made epidemic. And we could stop it today.”