Not all of Germany is against Vladimir Putin. Sahra Wagenknecht, a Left Party MP, recently defended him, saying he is not “the mad Russian nationalist” of caricature and sending weapons to Ukraine was a “US-driven policy” which played a role in provoking his invasion. Her views are quite common in East Germany and not only among the left. The far-right party Alternative for Germany, which has most of its support in the East, opposes sanctions and providing weapons.

A recent opinion poll asked whether Berlin should “be tough on Russia”: half of West Germans agree, but just a third of East Germans do. Some 58 percent of East Germans want Berlin to take an approach that doesn’t “provoke Russia.” Only 40 percent of West Germans agree.

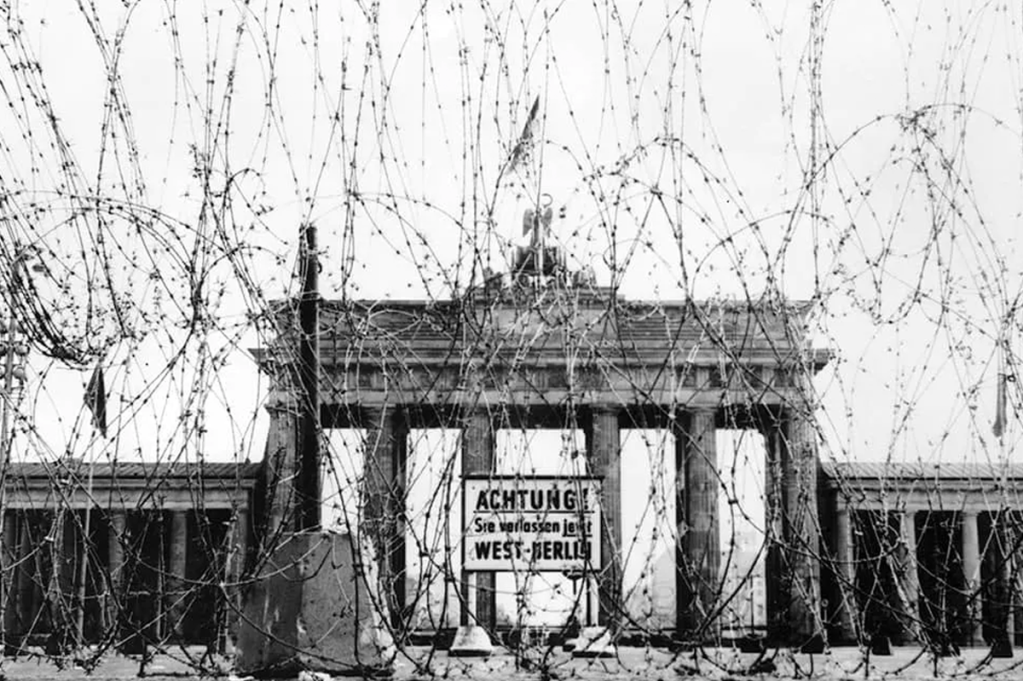

East Germany’s sympathy has nothing to do with nostalgia for the days of Moscow rule. Three decades have passed since reunification in 1990 and surveys repeatedly show most former citizens of the German Democratic Republic feel their lives have changed for the better. But Germany spent the Cold War years divided, affiliated to radically different military superpowers. So perhaps it’s not surprising that West Germany, which joined NATO in 1955 and became its bulwark in Europe, is now quicker to feel affiliation with this western alliance than us in East Germany, who had learnt to fear it.

What explains East Germany’s different attitude towards Russia than that of the Poles or Baltic states? Many Eastern European nations fought for centuries to defend themselves against Russia — while Germany has often stood by or even colluded as it sought to dominate its neighbors. So East Germans don’t share the same sense of existential threat. And while the Stasi years did leave deep psychological marks on East Germans, it didn’t lead to a long-lasting reappraisal of Russia’s role in Europe. In their view, the Soviets liberated them from Nazism. Injustice had been done to Russia by Germany, not the other way around. Poland rightly took a very different view having fought German and Russian brutality.

Unlike Eastern European states, the GDR was also never subject to Russification. It kept German colors on its flag, German uniforms on its army and German history in its textbooks. Many East Germans enjoyed consuming Russian culture alongside their own. They read Russian literature, learned the language and traveled to the Soviet Union to study. Throughout the Cold War, Russians remained faceless enemies to the West, while East Germans built relationships with them. Today, they find it hard to see them as the enemy.

In West Germany, there also exists an anti-NATO sentiment. In February, the MP Sevim Dağdelen said Ukraine’s behavior was “akin to a declaration of war on Russia” and a result of US and NATO “warmongering.” Veteran women’s rights activist Alice Schwarzer claimed Putin was given “a motive to act.”

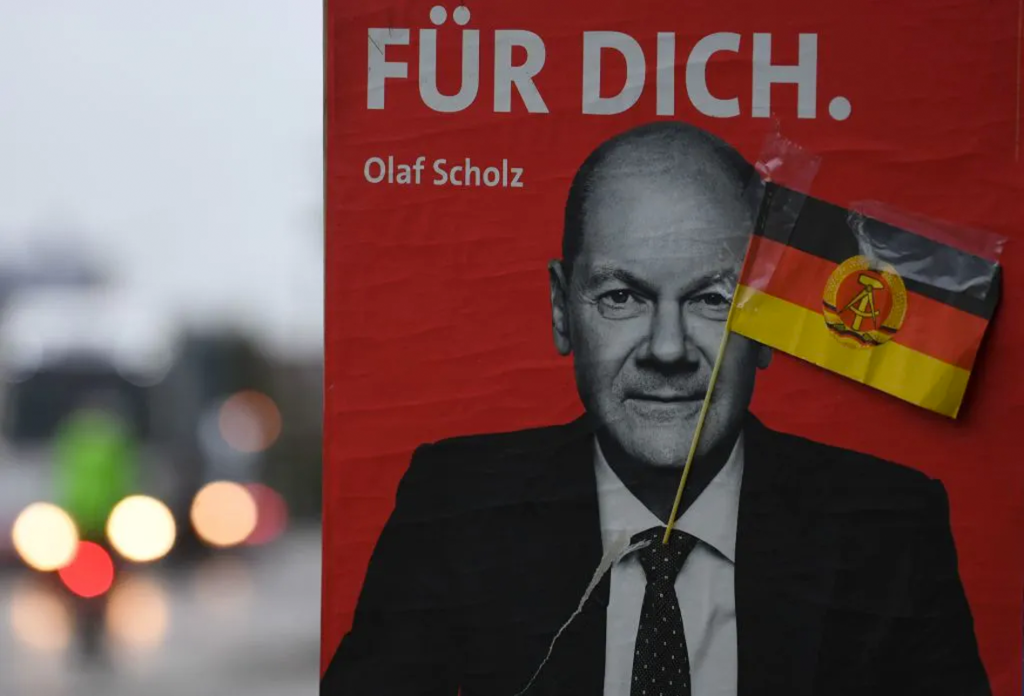

Chancellor Olaf Scholz once held anti-NATO views, too. In 1982, when he was deputy leader of the Young Socialists, he argued the arms race was fueled by an “aggressive-imperialist NATO strategy.” Now he’s calling for €100 billion to be added to defense spending — and wants to use the cash to buy American F-35s.

Scholz may never fully understand the way former GDR citizens see the world. But he should try. East Germans make up 16 million of Germany’s 80 million population — and it’s their region that will take the biggest economic hit from economic sanctions against Russia (the Druzhba pipeline, Nord Stream 1 and Nord Stream 2 all run to East Germany, providing thousands of jobs). Cutting economic ties with Russia is right and necessary, but the prospect causes real anxiety for East Germans.

Most East Germans experienced immense economic, social and ideological upheaval when the Soviet Union collapsed — and the fallout is still visible today. If Scholz can overcome his own youthful skepticism towards NATO, he should look for ways to bring his eastern compatriots along. Germany is still working out how to move on from its troubled twentieth-century history: as one nation and as part of the West.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.