Donald Trump thinks “tariff” is the “most beautiful word in the dictionary.” Today is “Liberation Day,” and the President is holding true to his campaign trail promise to impose tariffs on imports. Cars, steel and aluminum are expected to be hit with levies of up to 25 percent. A 10 to 20 percent universal tariff on all goods imported into the United States is also said to be on the table.

Trump isn’t the first to think tariffs are a secret weapon. A century ago, the British Conservatives were obsessed with tariffs. Like Trump, they saw them as an ideal tool to promote industrial revival and lower taxes. Unfortunately, as Trump will likely discover, the results were disappointing.

From the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846 until the Great Depression of 1929, free trade was an article of faith for the British electorate, who associated it with the prosperity of the mid-19th century. However, like the United States today, by the late 19th century, there were growing fears of national decline relative to emerging industrial powers such as Germany and the United States. The UK’s share of the global market for manufactured goods fell from 41 percent to 30 percent between the late 1870s and 1913.

At the same time, the Conservatives’ electoral strategy of securing working-class voters by emphasizing the importance of empire and the union with Ireland was losing its appeal to an electorate increasingly concerned with social issues. A new political approach was needed.

And so, in 1903, the then-Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain announced his support for introducing tariffs. Chamberlain was still technically a Liberal Unionist at the time, but that party had been increasingly allied with the Conservatives since 1886 and would ultimately merge with them in 1912. After some internal struggle, tariff reform became official Conservative policy.

On paper, tariffs offered a neat solution to multiple problems. Abroad, they would ensure Britain remained great by consolidating the British Empire. By erecting external tariff walls against countries outside the Empire, so the idea ran, the British government could then negotiate preferential trading agreements with its colonies and dominions. This, in turn, would keep them more tightly bound to the mother country and, in so doing, preserve Britain’s global influence.

Like Trump today, British Conservatives also hoped that tariffs would solve problems closer to home. With growing industrial competition, tariffs would protect UK industries, such as iron, steel and textiles, from “unfair” foreign competition that risked destroying the UK’s industrial base. As one economist argued in 1911, “England could not remain the workshop of the world; she is fast becoming its creditor, its mortgagee, its landlord.”

Echoing Trump’s desire to replace income tax with tariffs, Conservatives also hoped to use them to forestall the introduction of more progressive taxation. Instead of raising taxes on income, land, and inheritance to fund social reforms such as old-age pensions or unemployment relief, the plan was to fund them through tariffs.

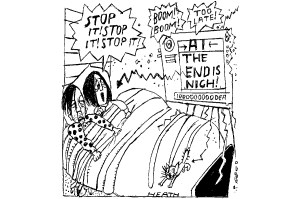

Unfortunately – as most economists would tell you today – tariffs were bound to fail, both politically and economically.

Politically, they backfired spectacularly and severely damaged the Tories’ electoral fortunes. First, at the 1906 election, only three years after the introduction of tariffs, the Tories suffered one of their worst-ever electoral defeats, collapsing to just 157 seats to the Liberals’ 400. They also lost both the subsequent 1910 elections to the explicitly pro-free trade “progressive alliance” of Liberal, Labour and Irish Nationalist MPs.

Like Trump today, British Conservatives hoped that tariffs would solve problems closer to home.

Tariffs continued to wreak electoral havoc even after the Great War. In 1923, the new Conservative leader and prime minister, Stanley Baldwin, unexpectedly called an election to secure a mandate for introducing tariffs. His gamble backfired: he threw away the parliamentary majority that his predecessor, Andrew Bonar Law, had won just the year before at an election where he had expressly ruled out introducing tariffs.

Tariffs failed at the ballot box due to fears they would drive up the cost of living by increasing the price of imported food on which ordinary Britons depended. A defense of free trade and cheap food was a defining issue at the 1906 and 1923 elections. With imports of key groceries such as fruit and vegetables already falling under Trump’s 25 percent tariffs on Canadian and Mexican imports, the electoral risks for Republicans are clear.

When the Conservative-dominated national government finally introduced permanent tariffs in 1932, after the Great Depression turned public opinion against free trade, they failed to deliver their supposed economic benefits. The promised preferential trading agreements with British colonies and dominions largely failed to materialize. Mindful of the likely electoral backlash, basic foodstuffs remained exempt from the UK’s new tariffs.

They also did little to revive British industry. While tariffs increased the share of goods imported from the Empire from 30 percent to 40 percent of the global total between 1932 and 1935, they did little to boost the UK’s declining share of global exports. Instead, protected by tariff walls, they served only to reward inefficient industries. If the United States wishes to help struggling domestic industries, the UK experience suggests tariffs are not the solution.

While Trump sees them as a panacea, the British experience shows tariffs only offer pain – particularly where they are seen as a threat to voters’ living standards. If he is even slightly concerned about the Republicans’ prospects in the midterms, Trump should take note – and learn a lesson from history.

Leave a Reply