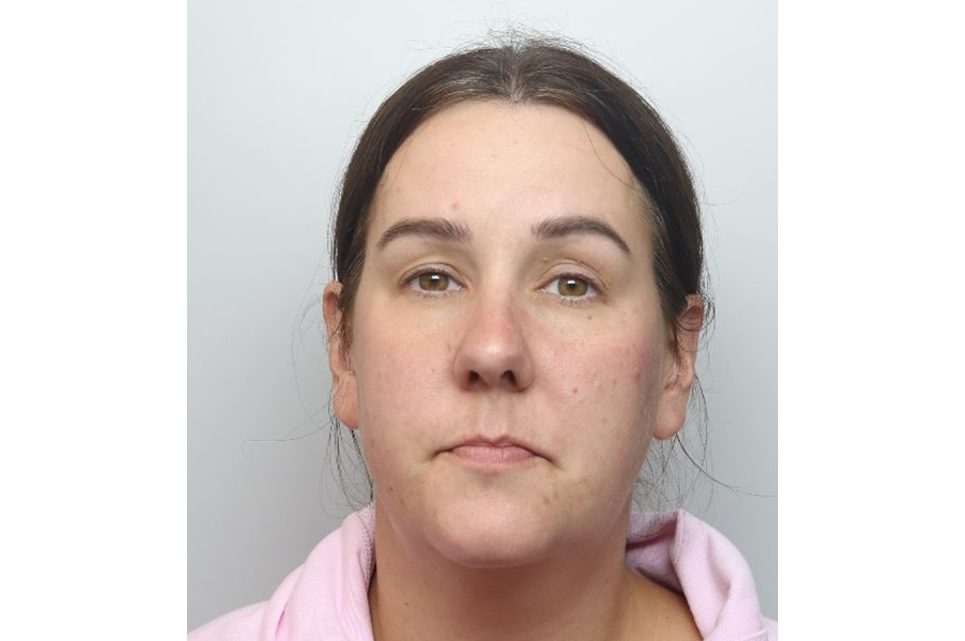

Does the United Kingdom need a First Amendment? That’s a question I’ve been thinking about a lot recently, given the government’s unrelenting assault on free speech. If Britons enjoyed the same constitutional protections as Americans, it would have been more difficult to prosecute anyone over the summer for social media posts “intending to stir up racial hatred,” the crime for which Lucy Connolly, the wife of a Conservative councilor, received two-and-a-half years last week.

The solution is not to pass a new law, but to repeal those laws that limit freedom of expression

But I remain skeptical. For one thing, there’s no mechanism in Britain’s constitution for creating a law that couldn’t be repealed by the next parliament. True, certain laws passed in the Blair and Brown years have proved hard to reverse, such as the Human Rights Act 1998, the Constitutional Reform Act 2005 and the Equality Act 2010, but that’s because they enjoy cross-party support, as well as the overwhelming support of the professional managerial class. I’m not sure a British version of the First Amendment would command such enthusiasm. There might at some future point be a referendum on replacing the Human Rights Act with a British Bill of Rights, one clause of which could resemble the First Amendment, and if the “Yes” side won, it would be difficult for a future government to overturn it. But would it offer more robust speech protections than Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights?

Here we get to the heart of the matter, which is whether the the UK’s supreme court could be trusted to prioritize freedom of expression over other countervailing rights, such as the right to privacy or — God forbid — a right not to be offended. Free speech will always have to be weighed in the balance against other considerations, which means the British people would be at the mercy of justices on the court, which to a great extent is already happening.

The supreme court has a mixed report card when it comes to defending freedom of expression, but it’s bound to get worse as the current Justices are replaced over time, given the gradual capture of the judiciary by radical progressive ideology. In America, the fact that the Court’s justices are appointed by different presidents (and enjoy life tenure) is a safeguard against ideological capture, but in the UK there is no such guarantee given that justices are appointed by unelected officials.

Could a British First Amendment be worded in such a way that it gives judges no wiggle room when it comes to prioritizing free speech? Doubtful. After all, Brittons couldn’t hope for anything more robustly worded than the actual First Amendment and even that wasn’t sufficient to protect freedom of expression in America for the first 140 years or so of its history. Plenty of censorial laws were passed after the constitution was amended, such as the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798 which made it a crime to “print, utter, or publish… any false, scandalous, and malicious writing” about the government. Absent the appointment of Oliver Wendell Holmes to the Supreme Court in 1902, the First Amendment would not be the bulwark against censorship that it is today.

But if this isn’t the solution to the erosion of freedom of speech in Britain, what is? It’s worth bearing in mind that the first ten amendments to the American Constitution were inspired by English Common Law, including the right to free speech. As interpreted by a famous Supreme Court decision in 1919, the First Amendment protects speech, including speech advocating insurrection, unless it will lead to “a clear and present danger.” That’s American for “breach of the peace” and echoes the Common Law principle that speech should be permitted unless it will stir up public disorder. The British government has departed from this principle several times, most recently in 1965 when the Race Relations Act substituted “stirring up public disorder” with “stirring up racial hatred,” a much more nebulous standard which has since been expanded to include stirring up religious hatred and hatred based on sexual orientation.

The solution, then, is not to pass a new law, but to repeal those laws that limit freedom of expression. The British people should think of themselves not as legislators, but as gardeners, pulling up all the weeds obscuring English Common Law. Admittedly, those weeds could be replanted by a Labour government, but it would have to restore them one by one, which would take up more parliamentary time than simply repealing a British First Amendment. Britain doesn’t have to copy their American cousins. All it needs do is resuscitate the Common Law breach of the peace principle that Americans in the Founding inherited.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.