There is a recurring type of incident that reflects the insularity of today’s media class: “Everyone was talking about it, but no one reported it.” There is no stronger indictment of contemporary media bias — it doesn’t arise just out of partisanship, nor out of opposition to reporting stories that displease our ruling class. It reaches the point of actively lying and covering up things any average American knows to be true.

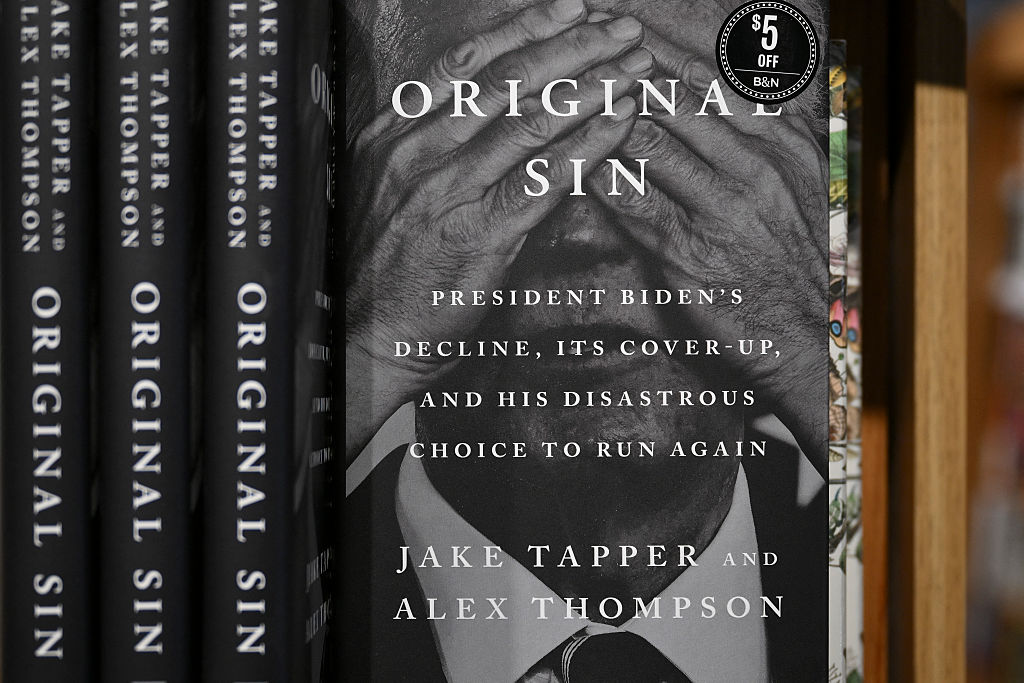

The most prominent recent example is found in the reaction to Special Counsel Robert Hur’s findings regarding Joe Biden’s hoarding of classified documents. Despite the wealth of evidence of illegal mishandling, Hur would not bring suit against the president, believing that a jury would be unlikely to convict a “well-meaning, elderly man with a poor memory.” All at once, it seemed like every White House journalist with a story about Biden’s age and heightened confusion was willing to address a wildly obvious truth: the man is declining precipitously before our eyes, and White House staff, angry as they might be about the coverage, are incapable of hiding it any longer.

The media doesn’t stop at pretending Joe Biden is a fully functional president. It goes far beyond that, lacking the self-reflection to consider the possibility that a major reason for journalism’s struggles in the post-Covid era is directly tied to this lack of public trust. For Republicans, there was the Hunter Biden laptop story; for Democrats, there was the collapse of the hopes of Russiagate; and for Independents (and everyone else) there was the total disaster of the rush to judgment on Covid. The media ran with health advice that was decreed, then debunked, policy responses that were decried, then approved — and, of course, the societal upheaval, disastrous job and educational loss and mandatory vaccines that turned out to be a lot less effective than they were sold as being. If someone lies to you that much, giving themselves awards along the way, eventually you stop taking them at their word.

Polls say trust in media is at an all-time low. But a better reflection than that can be found in what’s happening in the journalism business, where the effects of that lost trust are measurable and astonishing. Last year saw media job losses of over 21,400 — the worst non-Covid year since the financial crisis and Great Recession of 2008-09. The first two months of 2024 have seen the job losses continue; some prominent entities have shut down entirely. The Messenger, Jimmy Finkelstein’s latest outlet, laid off all 300 staffers; Sports Illustrated laid off almost its entire staff; and VICE announced it would stop publishing entirely. NBC News, CBS News, TIME magazine, the Los Angeles Times and Condé Nast all saw layoffs in the double and triple digits. Even the insulation of Washington wasn’t enough to keep journalists employed – the Wall Street Journal gutted its DC bureau, and NPR shut down its local DCist site to focus on audio. And BuzzFeed, which cut back its entire news division to save on costs in 2023, announced further cuts and spun off its Complex brand in February for cash — less than a decade after it was named one of the media’s “most valuable startups” by Business Insider, which itself cut 8 percent of staff in January.

The great hemorrhaging over the media landscape should give its members pause. But instead, they’re behaving like The Simpsons’ Principal Skinner: “Am I so out of touch? No, it’s the children who are wrong.” Rather than recruiting a more ideologically diverse newsroom or responding to the success of heterodox outlets on Substack, YouTube and Spotify by bringing similar voices into their commentary sections, they foment accusations of misinformation and disinformation, and even call on government entities to censor their freestanding competitors and keep the old guard in a protective bubble.

Politico’s national investigative correspondent, Heidi Przybyla, offered a perfect example of the media mindset in a February appearance on All In With Chris Hayes, where she attempted to describe the real danger of Donald Trump’s potential return to power as being his support among “Christian nationalists.” Citing her conversations “with a lot of experts on this,” Przybyla described these extremists: “They believe that our rights as Americans, as all human beings, don’t come from any earthly authority. They don’t come from Congress, they don’t come from the Supreme Court, they come from God.” Przybyla was promptly deluged on social media as people called attention to the many, many Americans who’ve shared this “extreme” belief, starting with the authors of the Declaration of Independence — in response, rather than expressing humility, she doubled down.

Back in December 2016, then-New York Times executive editor Dean Baquet reacted to the shock of Donald Trump’s election by addressing the newsroom’s lack of religious diversity. In an interview with NPR, he said, “We have a fabulous religion writer, but she’s all alone. We don’t get religion. We don’t get the role of religion in people’s lives. And I think we can do much, much better.” Eight years later, no one is doing much better at covering these basic, normal issues — and people are tuning out because of it.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s April 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply