The lion or elephant in the photo should be stone-cold dead. The hunter posing with it should be ugly, fat and preferably American. Cue to social media outrage from celebrities, journalists and online nobodies. Few things generate more furious likes and retweets than old, white men killing African mega-fauna.

Yet, as Barack Obama once said: “This idea of purity and you’re never compromised… you should get over that quickly. The world is messy. There are ambiguities. People who do really good stuff have flaws.”

In order to survive outside the parks, wildlife needs to have a value for rural Africans

As counter-intuitive as it sounds, African trophy hunting is a powerful conservation tool. To be clear: we’re talking about regulated hunting in Africa and not poaching which, together with habitat destruction, are the biggest threats to African wildlife.

“Europeans and Americans may not like to hear it but trophy hunting in Namibia has not only saved wildlife: it has helped increase populations, in some cases, by more than 200 percent,” says Stephan Albat, a Namibian farmer, in an interview on his farm near the Waterberg Plateau National Park in north-central Namibia.

Human demography is the destiny of African wildlife. Africa’s population is projected to grow from 1.4 billion today to 2.4 billion in 2050 and 4.2 billion in 2100. This will mean massively less space for wildlife. It’s wonderful that there are national parks and protected areas in Africa. But these are a tiny part of the continent and much land is taken up by the more than 60 percent of sub-Saharan Africans who are smallholder farmers.

Conflicts with large wildlife can be deadly for rural Africans. More than 100 people were killed by elephants in Zimbabwe alone in the first half of last year, whose population has surged to over 100,000 — more than double what the land can support. Hippos, crocodiles, lions and cape buffalo kill thousands of people in Africa each year.

In order to survive outside the parks, wildlife needs to have a value for rural Africans. It does this by creating jobs linked to wildlife tourism. But far more jobs and revenue are generated by hunting tourism which employs professional hunters, trackers, skinners and camp staff. Hunting crucially provides meat to rural Africans — reducing a reason for poaching — and hunting fees far exceed those of any photo-safari. (A trophy fee for an elephant can be over $33,000.) Follow the money: one big game hunter can equal 100 photo safari tourists.

What’s more, hunting takes places in remote, unfashionable areas rarely visited by regular tourists. Finally, it can make large wildlife wary of approaching people, which can protect crops and save lives.

If African mega-fauna is seen as having no value, then we shouldn’t be surprised if Africans shoot, poison and snare wildlife to protect their families, livestock, crops and to provide meat. Kenya, which banned trophy hunting in 1977, still battles poaching, with the elephant population falling from 150,000 in the 1960s to 36,000 in 2021. In Namibia, which uses hunting as a crucial tool in wildlife management, the elephant population has risen to more than 24,000 from 7,500 in 1995 — a rate of approximately 5 percent per year. Generally speaking, there are too many elephants in southern Africa, which allows hunting, and too few in east African countries like Kenya, which ban it.

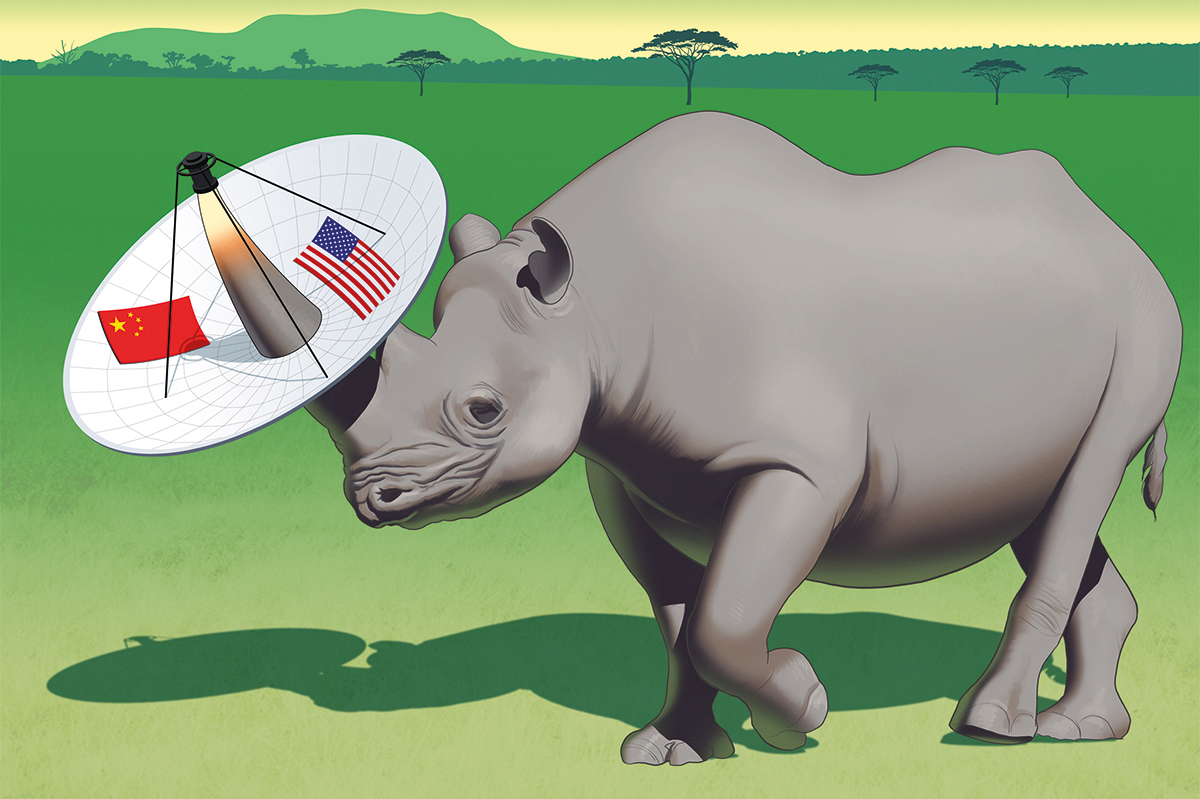

In an age of postcolonialism theory, it’s jarring to see the neo-colonialism of Europeans and North Americans aimed at Africa when it comes to the continent’s natural resources. Africans are not only lectured on how to use their wildlife but are implicitly told they are too stupid to do this themselves. This is the message of calls for a US ban, a planned UK ban and similar calls in Germany to prevent the import of hunting trophies that are legal both under African law and the Convention on International Trade Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES).

African leaders are also told not to drill and use the continent’s vast quantities of natural gas and oil, despite the fact that almost 600 million sub-Saharan Africans have no access to electricity. At the beginning of the year, German development aid minister Svenja Schulze proclaimed she won’t support just any old jobs in Africa but only those that are “social, environmental or strengthen women.” Worthy? Perhaps. But South Africa’s current unemployment rate, for example, stands at 34 percent.

The Namibian model is a way to protect and increase African wildlife. Namibia now has more large wild animals than at any time in its recent history. Probably no other country in Africa has used hunting as effectively to expand its population of mega-fauna.

The opposite approach — banning hunting, as in Kenya — has contributed to the decline of common Kenyan wildlife by 70 percent and more. At the same time, the number of sheep and goats in Kenya has increased more than 75 percent.

How does it work in Namibia? It’s worth listening to Stephan Albat, the Namibian farmer. He studied Forest Science and Wildlife Management in South Africa and manages farms in Namibia with 24,000 hectares (59,000 acres). On these farms he has 2,600 beef cattle and about 4,000 large wild species including oryx, kudu, eland, hartebeest, giraffe, zebras, impala and warthogs. Albat has drilled wells and his windmills pumping water on the arid farms are a boon to all wildlife including a huge variety of birds.

Guest hunters on the farms shoot about 1,000 wild animals a year. Hunters pay the equivalent of approximately $220 for each culling animal killed and between $435 and $1,400 for a large, older trophy animal. The meat from wild animals can only be sold in Namibia and southern Africa because under European Union regulations Albat can export only beef to Europe. He earns the equivalent of $1 per pound of antelope and 50 cents for warthog.

The farms employ eighteen full-time workers and up to twelve seasonal workers. “If we did not have the income from trophy hunting and culling, I would reduce the number of large wildlife species on the farms to 500 from the current 4,000 and replace them with cattle,” says Albat. “As we say: if it pays it stays.”

The upshot: trophy hunting, the culling of young and injured animals and the sale of their meat supports the existence of 3,500 large, grazing, wild animals on Albat’s farms. This income allows him to tolerate losses caused by the largest animals such as eland and giraffes which damage fences and graze heavily. Leopards may kill some cattle but they have a value to the farms as a species that can be hunted under strict licensing regulations.

So, the next time you see that photo of an ugly hunter posing with a dead animal, recall the untidy nature of the world and the fact that people doing good stuff may not look the part. If you must virtue-signal that African trophy hunting is a great evil of our age, keep your true message and its impact in mind.

To do otherwise ignores the environmental pressures of Africa’s fast-growing population. You’re promoting a tidal wave of more cattle, sheep and goats and far less wildlife. You’re disempowering Africans seeking to forge their own destiny.

Banning trophy imports makes rich westerners feel good — but in effect it’s telling Africans to shut up and provide more beef for European burgers.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.