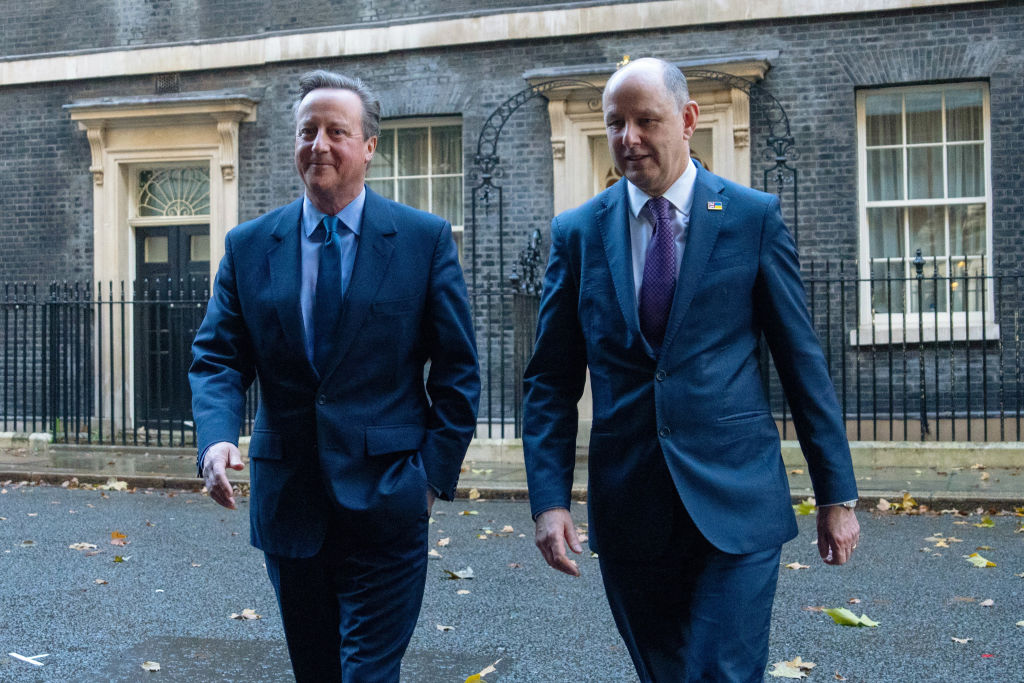

All political careers end in failure but few return to prove it a second time. David Cameron, forced to resign as Britain’s prime minister after his defeat in the European Union referendum, has been brought back, given a peerage and appointed foreign secretary. His appointment followed the sacking of Suella Braverman as home secretary and James Cleverly’s sidewards move to replace her.

Expect Rishi Sunak’s stenographers in the press to gush over this masterstroke. A heavy-hitter in the cabinet. An experienced pair of hands at the Foreign Office. A return to serious, grown-up politics. Labour will be rattled now! Any such talk will be guff. This is not genius, it’s desperation. The prime minister wanted to spend his time in No. 10 enthusing about AI and schmoozing shoeless tech bros just flown in from Palo Alto, scrolling through Sunak’s Wikipedia entry on their way in from Heathrow. Unfortunately, the world had different ideas and we find ourselves with a prime minister wholly out of his depth on international affairs and security.

Hence Cameron. It’s a choice, certainly. Sir John Major, perhaps. Theresa May, maybe. William Hague, even. But Cameron? You can’t blame Sunak for wanting a bit of gravitas at the Foreign Office, a statesman to do the DC-Brussels-Beijing stuff, especially after Cleverly’s fourteen months as a mouthpiece for the policy preferences of the department’s civil servants. But Cameron’s tenure in No. 10 is hardly associated with big wins for the UK on the international front. That Sunak considers him the best man for this brief underscores how little he knows about this brief. A foreign policy flyweight has brought in a featherweight.

Cameron was, with George Osborne, co-architect of the early 2010s pivot towards China, and described his time in Downing Street as a “golden era” for Sino-British relations. One of his first key foreign visits was to China, where he pledged to “make the case for China to get market economy status in the EU.” Under Cameron, the UK brushed aside American concerns to become a founding member of Beijing’s Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, a soft-power boost for the communist dictatorship. At the time, a senior White House official told the Financial Times that the United States had become “wary’ of the UK government’s “constant accommodation of China,” a rare rebuke for a friendly country.

After China banned British MPs from visiting Hong Kong to observe the human rights situation there, the Commons foreign affairs committee said it was “profoundly disappointed with the UK government’s mild response to that unprecedented act.” When Cameron’s 2012 meeting with the Dalai Lama provoked outrage from Beijing, No. 10 briefed that the prime minister would not meet the Tibetan spiritual leader again. Lord Patten described Cameron’s China policy as a “well-meaning failure” and told a Lords committee: “We jumped through hoops in order to try to become China’s greatest friend in the rest of the world, and I think the Chinese must have laughed up their sleeves while going along with all that… The tune has been played by China rather than the Treasury.”

Cameron’s foreign policy also ran into trouble in the Middle East and North Africa. His 2011 intervention in Libya, carried out alongside the French, was later filleted in a report by the Commons foreign affairs committee. The committee concluded that the policy “was not informed by accurate intelligence,” based on an “overstated” threat to civilians and failed to realize the presence within the anti-Gaddafi forces of “a significant Islamist element.” The intervention led to “political and economic collapse, inter-militia and inter-tribal warfare, humanitarian and migrant crises, widespread human rights violations, the spread of Gaddafi regime weapons across the region and the growth of ISIL in North Africa.” The committee singled out Cameron and his decision making as “ultimately responsible” for the debacle.

This is a man with astonishingly rotten political judgement

Given the situation in Gaza will be top of the new foreign secretary’s in-tray, Cameron’s dubious back catalog is also relevant here. As prime minister, he repeatedly described Gaza, under a joint Israeli-Egyptian maritime embargo, as a “prison,” including telling the Commons that “everybody knows that we are not going to sort out the problem of the Middle East peace process while there is, effectively, a giant open prison in Gaza.” Cameron urged the Israelis to end the embargo and said “the blockade actually strengthens Hamas’s grip on the economy and on Gaza.” The embargo was put in place in response to Hamas smuggling in weapons from Iran to fire at Israel. The events of October 7 demonstrated the wisdom of the embargo and the lethal foolishness of pontificators like Cameron in trying to undermine it.

There will be more time in the coming days to rake over Cameron’s foreign policy failures as prime minister, but there is a more general point that must be made. This is a man with astonishingly rotten political judgment. The passage of time and the absurdities and indignities of the last seven years may have had a Lethean effect on our collective consciousness, but Cameron was a fount of error and ineptitude in government. Like all public schoolboys, he deploys that Jedi mind trick to convince the hoi polloi he is calm, in charge and following a plan. In fact, he is like so many of his class, a chancer.

He took a chance in calling a referendum on the UK’s membership of the EU, sure that he could secure a substantive package of reforms from Brussels and seeming not to have entertained the thought that he might lose the vote. His scurrying off after the country voted Leave was less making way for the Brexiteers to carry through their project and more bailing out so someone else could clean up his mess. He took a chance in devolving two additional tranches of powers to the Scottish Parliament and giving Alex Salmond a referendum on independence. The UK came perilously close to losing that referendum and the SNP simply banked the extra powers and stepped up its efforts to use Holyrood as a constitutional battering ram against the Union. He took a chance that he could lobby ministers and civil servants on behalf of Greensill Capital, leading the Treasury committee to conclude that he had shown “a significant lack of judgment.” What he didn’t lack, as that episode demonstrated, was spivishness, abiding by the letter of the law while behaving in a way most Britons would think degrading of government and of the office he formerly held.

So David Cameron gets another chance to fail in a pivotal post at a time of grave threat and instability across the globe. Cameron is as unfit for this job as Rishi Sunak is for his.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.

Leave a Reply