Who is to blame for the devastating floods that hit Spain’s Valencia on October 29? The mob that surrounded King Felipe at the weekend and drove Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez out of town with a hail of mud and stones was angry at the failure to forecast the flood and warn people to get out of its way. The mainstream media would like us to be angry at man-made climate change for causing the storm — like the BBC putting out a headline the very next day: “Scientists say climate change made Spanish floods worse.”

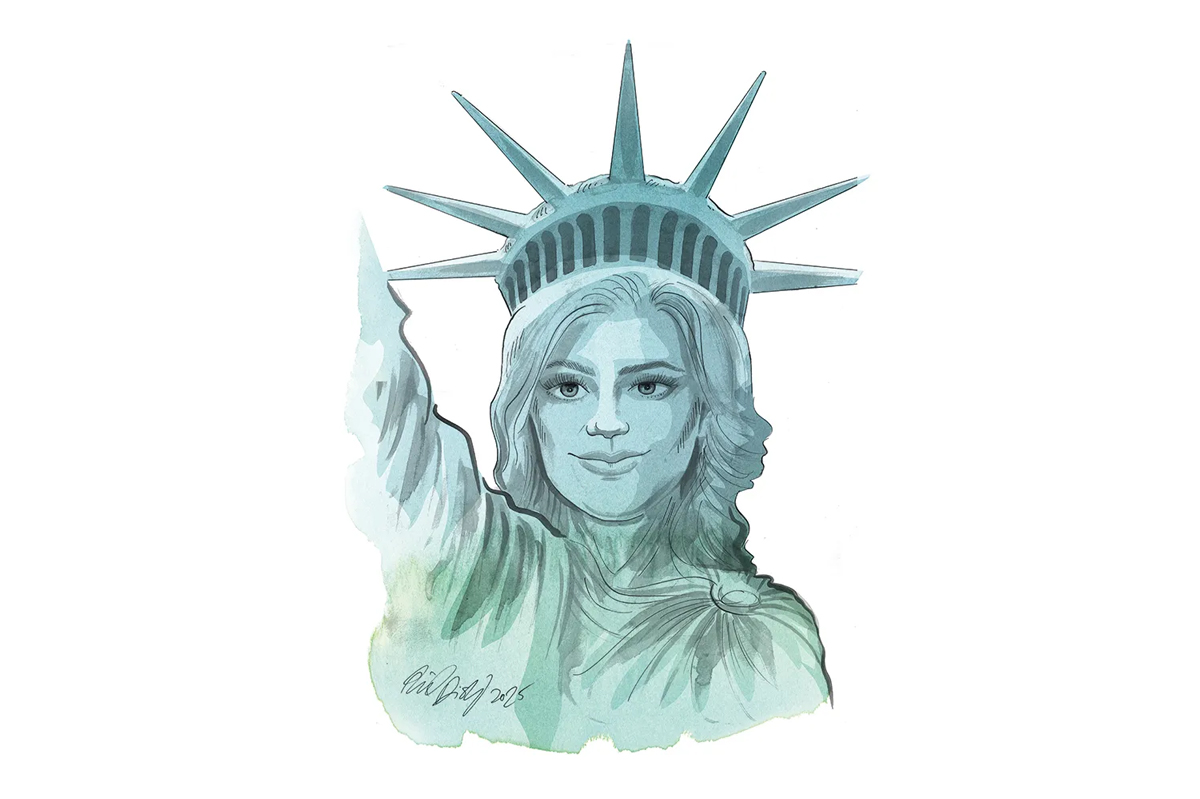

Charts of rainfall in Spain show no trend towards a higher frequency of more extreme downpours

Yet Valencia had a similarly terrible flood in 1957, in which eighty-one people died, long before climate change became the go-to excuse for any bad weather. After that flood, to prevent a recurrence, the Spanish government built a string of dams in the hills to hold back water and diverted the Turia river away from the city. For more than six decades the system worked well. Why did it fail this year? Because the unusually warm sea made for an unusually bad storm, say some.

Yet charts of rainfall in Spain show no trend towards a higher frequency of more extreme downpours. The data analyst Jose Gefaell published a graph this week of the number of rainfall events in Spain in which more than 100 liters fell per square meter in twenty-four hours. It shows, if anything, a slight decline. The three worst such downpours all happened in the province of Valencia — but in November 1987, before global warming apparently kicked in.

In the past few years, the Spanish government has been removing dams at a furious rate. Under a European Union program to encourage the restoration of rivers to their wild state for the benefit of fish migration, Spain set about dismantling barriers of all kinds. In 2021 it got rid of 108 dams and weirs; in 2022, another 133. That year, according to Dam Removal Europe, a coalition of seven green pressure groups, it was Europe’s proud league champion at dismantling them. Last year it was second only to France.

Some dams were removed in the hills around Valencia but it turns out they were small irrigation dams, not reservoir dams, so they would not have made much difference last week. However, the failure to build a new dam may well be partly to blame. The Cheste dam in the Turia catchment was specifically designed to prevent flooding, to “regulate the flows coming from the upper basin of the Poyo and Pozalet ravines.” It was approved in 2001 as part of a National Hydrological Plan.

Objections from people in Aragon to separate parts of the plan that would transfer water between regions led the socialist Jose Luis Rodríguez Zapatero to promise to repeal it when running for prime minister in 2004. He kept his promise and the Cheste dam was an unintended casualty. Could it have saved Valencia? Possibly. The city of Aragon was saved last month by a dam built by the emperor Augustus.

As it happens, the same question had been asked a month earlier about the floods in North Carolina following Hurricane Helene. The area around the city of Asheville was devastated, while downstream Nashville was fine. Stephen McIntyre, a Canadian climate analyst, noticed a possible reason for this. In the 1930s, after a series of terrible floods, the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) was charged with building dams throughout the catchment of the Tennessee river, to soak up unemployment, generate electricity and alleviate flooding. It built forty-nine dams over the next forty years, including a huge one above Nashville, and the devastating floods of 1916 and 1927 became a distant memory.

But one district rejected all its proposed dams because of local opposition: Asheville. A dozen dams were planned for the French Broad river and its tributaries around Asheville but they were never built. Had they been, it is likely that the floods of this year would have been far less terrible.

McIntyre writes: “[Hurricane] Helene was indistinguishable from prior large storms e.g. 1916, 1793. What Helene demonstrates is something that has been ignored or concealed by the [Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change] — that the long-term societal project of river dams for combined purpose of flood control and electricity has successfully reduced ‘climate-related’ deaths. But, if you check IPCC reporting, the climate science community instead frets about CO2 emissions in the construction of such dams.” The TVA itself now bangs on about climate change.

Back in 2011, Brisbane in Australia suffered a devastating flood, which some people argued was exacerbated by the fact that the very dam built to hold back water after several previous floods had been allowed to fill before the cyclone arrived. The general view of climate scientists at the time was that Australia had entered a period of prolonged if not permanent drought and every drop was needed. So perhaps when the Wivenhoe dam began to fill up everybody was still thinking about drought and forgetting why the dam was there. In the end a long public inquiry exonerated the dam operators of blame.

Climate change is happening and might indeed make flooding worse: a warmer atmosphere can hold more moisture after all. But if you think that is the case, then you have all the more responsibility, surely, to take measures to plan for more flooding and work out ways to prevent it doing so much damage. Even if dam removal has not contributed this time, perhaps dam building could help next time.

This is known to climate activists as “adaptation” and they dislike it. They prefer “mitigation” through reducing emissions. I am never quite sure why, but I think it is because they fear that if we find ways to make climate change less harmful we might end up being less angry about it. Throwing soup at paintings would then be less alluring as a profession.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.