If the coronavirus were as deadly as the bubonic plague, which killed about a third of the population of Europe in the 1340s, there would be no doubt about the need for extreme measures. But this virus spares far more people than it kills, and is sometimes mild to the point of invisibility, even as it proves lethal to others. It’s almost as though nature had calibrated the virus exactly to the point where risk-avoiders saw the lockdown as vital for survival while risk-accepters saw it as so economically destructive as to be worse than the disease itself.

America is polarized not just politically but in its attitude to risk. Half the nation is so risk-averse it wants its teachers to give children ‘trigger-warnings’ before showing or telling them anything unpleasant, wants to ban peanuts and sugary snacks from schools, and wants to outlaw smoking. The other half is so accepting of risk that it plays with guns, drives too fast, eats fatty food, and puffs on cigars. Present this divided population with COVID-19 and you have the perfect recipe for rancorous disagreement.

History is the fund of experience to which we turn when wondering how to deal with new problems. American history shows us a lengthy catalogue of risky behaviors and a tradition of citizens pointedly ignoring government instructions. In the early 19th century, for example, western settlers seeking farms moved into each new territory ahead of federal land surveyors, even though they knew that squatting was forbidden. Often, they are honored for their initiative, as in Oklahoma, which calls itself the ‘Sooner’ state because illegal early arrivers, the ‘sooners’, seized the best land and usually kept it.

Western settlers were often ahead of the army too, provoking chronic and barbaric frontier warfare with Native Americans. In California, Washington, and Oregon the settlers were even ahead of the nation’s foreign policy, settling on land that did not become part of the USA until 1848. Frontier risks were high, but so were the rewards.

Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House on the Prairie books, based on her family’s experiences in the 1860s and 1870s, depicts a settler family making successive moves into ever-more-dangerous territory. Often outside the law, they needed to be completely self-reliant and knew that an accident or illness would have shattering consequences, but they took the risks anyway. Some readers love ‘Pa’, the family patriarch. Others are infuriated by his reluctance to stay in a safe place for the sake of his wife and daughters.

Western movies exaggerate the frequency of street gun battles, but there’s no doubt that frontier towns, especially in the early days, when they contained many more men than women, were dangerous places, where accident, disease, and other people could all be sources of sudden death. Men’s prickly sense of honor and the tradition that a man will ‘stand his ground’ rather than seek conciliation contributed to a routine acceptance of violence and disregard of the law. Gun advocates today honor this tradition and regard themselves as the men who stand on freedom’s front line.

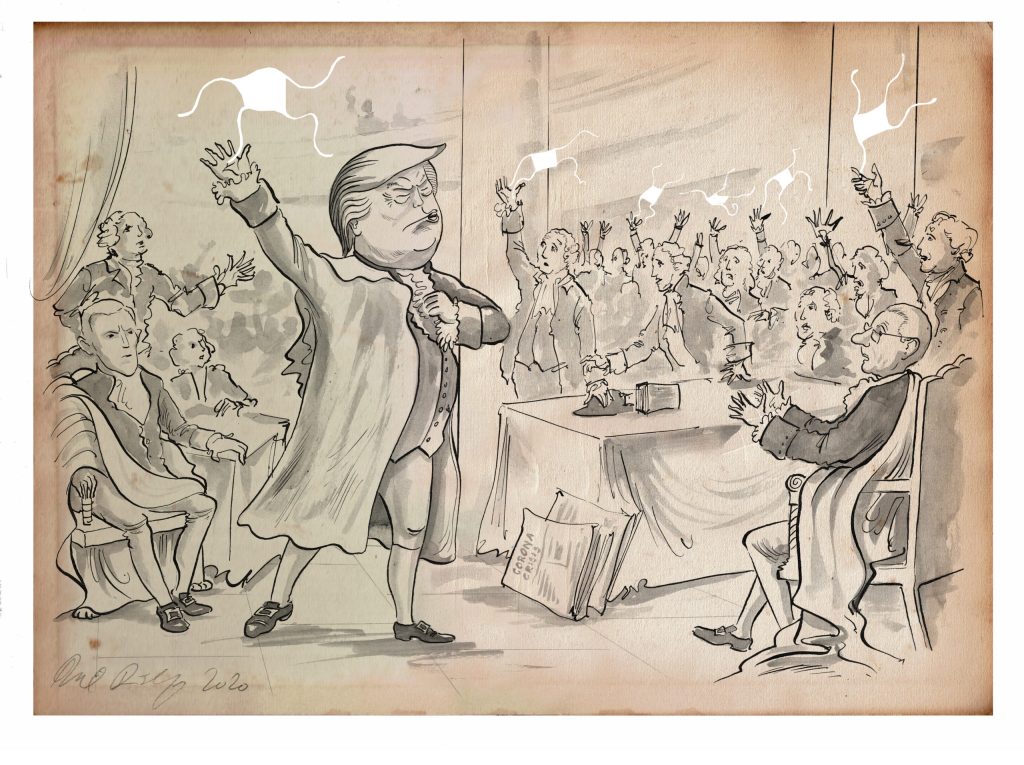

Still, how could Americans not feel ambivalent about government? The United States came into existence by rejecting the powers that be. Patrick Henry’s spellbinding speech against the British in 1775, which ended with the rallying cry ‘give me liberty or give me death’, helped persuade his fellow Virginians, including George Washington, to take up arms. It’s interesting to note that some of anti-lockdown protesters have adapted that quote as a slogan: ‘Give me liberty or give me COVID-19’. Ever since the Revolution, state and federal governments have had to contend with citizens appealing to this spirit of resistance. Millions today love President Trump because he says he’s opposed to big government. That’s a paradox, obviously, but it’s a paradox many citizens seem to relish.

Earlier epidemics in American history show the same range of behavior that we’re witnessing now and the same range of political responses. In Philadelphia’s yellow fever epidemic in the late summer of 1792, for example, selfless doctors and nurses helped the sick and dying, exposing themselves to danger and also dying in large numbers. Of 50,000 in the population of what was then the nation’s largest city, about 5,000 died. At the same time, Philadelphia’s least scrupulous citizens seized the opportunity to gouge their neighbors by jacking up the price of vital goods and services.

Then, as now, no one understood a disease that was transforming everyday life (only a century later would mosquitos be identified as the vector). Quakers thought the epidemic was a reproach from God, who had been angered by some risqué theatrical performances. In those days, before the founding of Washington DC, Philadelphia was home to the federal government. President Washington, dutiful and level-headed, was hard at work there through the first six weeks of the epidemic. The government of the state of Pennsylvania, by contrast, discovered a dead body on the steps of their State House and at once adjourned.

When cholera visited New York City in 1832 the process repeated itself, bringing out the best and the worst in human nature and turning a busy city into a ghost-town. Manhattan’s streets were as silent as they are now. One observer wrote, ‘There is no business doing here if I except that done by cholera, doctors, undertakers, and coffin-makers. Our bustling city now wears a most gloomy and desolate aspect. One may take a walk up and down Broadway and scarce meet a soul.’ As usual, the immigrant poor and racial minorities suffered more than the rich. The patrician leader of New York’s historical society wrote that most of the victims were ‘dissolute and filthy people huddled together like swine in their polluted habitations’.

***

Get three months’ free access to The Spectator USA website —

then just $3.99/month. Subscribe here

***

As we look ahead, we’re already aware that when an effective vaccine is developed, some Americans are going to refuse it, even at the risk of their lives. As they see it, vaccinations are one of the more sinister techniques government uses to coerce citizens, reduce freedom, and manipulate all but the most vigilant. But anti-vaccination ideas now show up across the political spectrum, not just on the right. On the left, the feminist health movement of the 1970s and 1980s taught women to challenge the authority of male doctors, while environmentalists queried America’s reliance on an ever-lengthening list of new chemicals. Meanwhile, the credibility of pharmaceutical companies just keeps on sinking. From being the national benefactors who helped Dr Jonas Salk spread the miraculous polio vaccine in the 1950s, they have become the most hated of all corporations for creating a national opioid epidemic.

History helps us understand the present but it doesn’t help us predict the future. Too many factors and too many unknowns are involved. The anti-shutdown Swedish government may turn out to have taken the right approach, but it may also have condemned thousands to early graves. Here in America conflicting views about health, safety, risk, and government will persist into the future and I expect that we will emerge from the pandemic with none of the big questions answered once and for all.