Solidarity usually suggests physical proximity: goodwill spreading with hugs and cozy chatter. But when you have a crisis with social distancing as an antidote, is that a barrier to comradeship? Far from it. On social media, videos of Italian flash-mobs singing to their neighbors have been shared, as well as petitions to test British National Health Service staff and footage of the ‘Viva los Medicos’ (long live the doctors) mass shout-outs from Spanish windows. Online solidarity overcomes borders, all the more so during a global pandemic. But Europe, which has been described as the ‘epicenter’ of COVID-19, has its own particular flavor of solidarity.

It was the growing outbreak in Italy that really brought attention to coronavirus across the continent. Sadly, disaster usually has to cross the Mediterranean for Europeans to sit up and notice. European nations have a long history of attacking each other’s castles and rolling tanks over each other’s corn-fields, but the continent also has an impressive history of solidarity. Dive into the history books and you quickly find examples. There were of course the under- and over-ground networks of the world wars, but it’s often the lesser-known events that illustrate the depth of this solidarity, from volunteers converging on Greece for its War of Independence (amongst them the ill-fated Lord Byron, numerous Prussians and a French fencing teacher posing as a cavalry officer) to the amateur guerrillas of the Spanish Civil War.

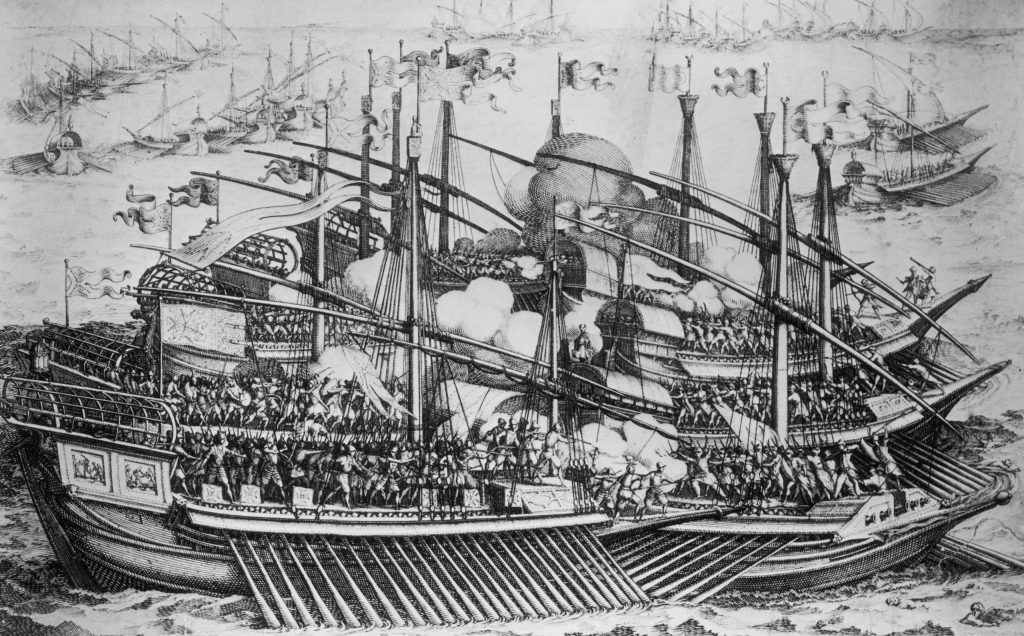

One event that may offer a little insight for today is a sea battle from 1571. At the time, the Ottoman Empire was seen as the gravest threat to Western civilization. The Spanish Empire, the Republic of Venice and the Papacy put aside their long-held differences and came together to form the Holy League which included, among others, the Republic of Genoa and the Spanish Netherlands. Volunteers joined from all over Europe, including a large contingent of Germans, Scandinavians and Scots. Among the volunteers was the Spanish writer Cervantes, who would lose his left hand. They saw the Ottomans as a threat worth uniting against, a menace not only to Christendom but to the European economy and their accustomed way of life.

Kick-started by the Ottoman seizure of Cyprus, the League managed to suppress their squabbles threatening to bubble over and reached Lepanto on the coast of western Greece with an armada of more than 200 ships, 40,000 sailors and 20,000 troops, led by the swashbuckling John of Austria, bastard half-brother to the King of Spain. Although outnumbered in terms of ships, they had more than double the number of guns as the Ottomans, as well as six fully-armed galleass ships, too high for the enemy to board. The battle resulted in a famous victory for the League, celebrated by the new printing press. Pamphlets broadcast the result, inspiring celebratory masses and festivities, lurid paintings and triumphal poems.

For many in Europe, the Ottoman Empire had been unassailable and relentless, tearing its way around the Mediterranean and Balkans. The victory at Lepanto was seen as the stemming of the tide, and although the West’s conflict with the Sultanate persisted, Lepanto marked the moment when the pendulum began to swing back the other way. The battle shouldn’t be romanticized, or oversimplified. European divisions persisted, and the conflict was as much a battle of economic systems as religious or cultural identity — pitting the labor-based Ottoman model against Western mercantilism. But as we face a new threat to western civilization, the story of unity in the face of a common peril holds a lesson for us today.

Europe’s greatest strength is its communications. In earlier centuries this was enabled by geography — our network of rivers and relatively benign landscapes. Later it was enabled by technology — from the printing press, which spread the news about Lepanto, to the telegraph and railway, to the internet today. Europe has always been good at spreading ideas, but the same goes for diseases. Our interconnectedness will help us tackle this threat, but it’s also a part of the challenge. History offers a measure of hope in these dark times, as well as a warning to brace ourselves for the long haul.

Nick Jubber is author of

Epic Continent: Adventures in the Great Stories of Europe. This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.