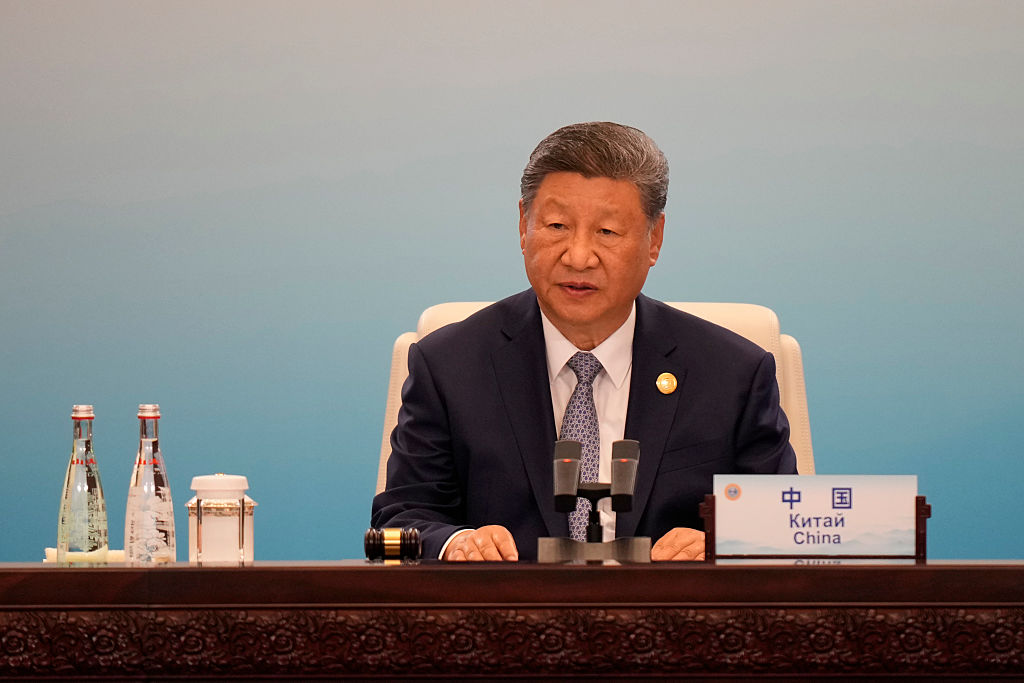

The first casualty of informational war is truth. The first American casualty of COVID-19 was the myth that the United States can ‘manage’ the rise of China as a world power through mutual interest. That mutual interest was only ever economic. Naturally, most of our politicians, business leaders and commentators explained it as strategic too: as technocracy calls GDP the index of human happiness, so it identifies strategic interests with economic ones. The coronavirus crisis has, however, exposed an essential strategic antagonism between the United States and China.

‘‘What made war inevitable was the growth of Athenian power and the fear which this caused in Sparta,’ Thucydides wrote in History of the Peloponnesian War. In Destined for War (2017), Graham Allison argued that established powers attack rising powers in order to preempt their own eclipse. COVID-19 is the latest in a series of factors that are dissolving common interests, worsening strategic stresses, and pushing America and China into what Allison calls the ‘Thucydides trap’. On Tuesday, President Trump shifted from praising China’s response to COVID-19 to speaking of the ‘Chinese virus’. On the same day, the Chinese foreign ministry revoked visas for Americans reporting for the Wall Street Journal, the New York Times and the Washington Post.

The closing of borders must necessarily lead to the contraction of supply chains. So must the closure of options and expectations. The United States government keeps its military supply chains within its borders in the interest of national security. For similar reasons, the United States pressures allies not to develop their own military industries and to buy American weaponry instead. This is a strategic interest, domestically and globally. The same should have gone for the medical supply chain. But it didn’t. Outsourcing the production of medicines and medical equipment is now revealed for what it was: greedy, reckless and feckless.

This coronavirus is not the common cold, but the COVID-19 blame game is producing a cold war. The American people blame the Chinese people for eating strange food and buying it at wet markets, and American media blame the Chinese government for not reacting quickly enough to the outbreak at Wuhan. Zhao Lijian, a spokesman for China’s foreign ministry, blames the US military: ‘It might be US army who brought the epidemic to Wuhan,’ Lijian tweeted in Chinese and English last Thursday. ‘Be transparent! Make public your data! US owe us an explanation!’ The PRC habitually monitors and scrubs China’s social media sites, but it allows this and other conspiracy theories to circulate online. On Monday, Mike Pompeo issued a demarche to China’s foreign ministry, expressing ‘strong US objection to efforts to shift blame for COVID-19’.

The US’s strategic posture toward China has already shifted under the Trump administration. If the COVID-19 death toll in the United States is high and the economic damage significant, that shift will accelerate, and quickly. The US is already caught in great power rivalry with China in the Pacific rim, while at the same time being excluded from the Chinese-led order that is developing in central Asia. A shift into open antagonism means both sides taking rapid steps into the ‘Thucydides trap’.

Thucydides, being a historian, used ‘inevitable’ in hindsight. But war isn’t inevitable, until it is. In four of Allison’s 16 case studies from the last 500 years, statesmanship stopped the trap from springing. There’s also the problems of reliable information and accurate interpretation. Where Tacitus praises the German tribes in order to implicitly criticize the decay of republican spirit in Rome, and Rousseau idealizes the Spartans to criticize the unmanly ancien règime of the Bourbons, Thucydides the Athenian blames the rise of an intolerable rival. But the true cause, Donald Kagan argued, may have been closer to home.

The ruling classes of Athens and Sparta had, Kagan argued in his New History of the Peloponnesian War, avoided conflict by close co-ordination: an ancient analogue to Niall Ferguson’s mutual-interest ‘Chimerica’, which now resembles a fantasy, like the ancient Greek chimera after which it was named. To Kagan, it was less the rise of Sparta that caused the war, and more the rise of aggressive leaders either unable to control popular anger, or determined to manipulate it for their own advantage. But that couldn’t happen here, right?