The bullet train from Beijing to Shanghai is the fastest in the world. It takes just over four hours to travel the 819-mile journey. From the train, it is impossible to ignore China’s economic success. There are cities the size of London that many westerners will never even have heard of. They are filled with glass towers and shopping centers, selling Cartier watches and Gucci bags.

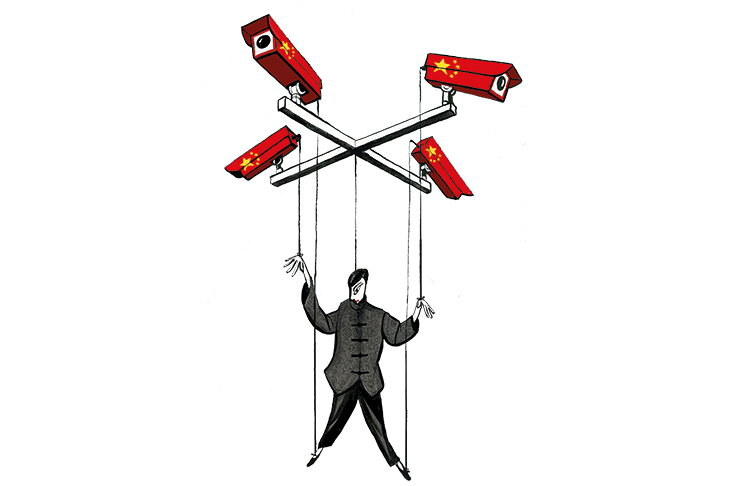

As the train sets off from each station, an announcement plays in both Chinese and stilted English: ‘Dear passengers, people who travel without a ticket or behave disorderly, or smoke in public areas, will be punished according to regulations and the behavior will be recorded in the individual credit information system. To avoid a negative record of personal credit please follow the relevant regulations and help with the orders on the train and at the station.’

As a technology journalist, I’m used to hearing Silicon Valley executives talk about how liberating new technology is. Yet this announcement startled me. It was a reminder that the same technology that has transformed liberal democracies is now starting to be used by authoritarian governments who want to tighten their grip on society.

‘Personal credit’ is essentially a permanent record of an individual’s behavior. In the case of the train announcement, the record is maintained by China’s transport department. If you’re caught traveling without a ticket or smoking on the train, you’ll be put on a blacklist. You may even find yourself banned from the railways.

In principle, this might seem like a good idea. But what gives the system a sinister edge is the government’s stated intention. By 2020, it wants to join up the railway blacklist with similar blacklists held by other government departments, municipalities and even private sector businesses. These records will then form part of a national ‘social credit’ system.

Social credit works in a similar way to how we rate our Uber drivers and Seamless orders. It allows individuals to be rated and scored. Good behavior is rewarded with points, while bad behavior is penalized. Run a red light? Lose some points. Donated to charity? Bonus points. Sold contaminated food in your restaurant? That’s going to hit your social credit rating hard.

The score is constantly updated. If it falls below an acceptable threshold, then it’s game over. You could be denied the right to travel, purchase luxury goods or gain access to services. In some cases, you may even be publicly shamed with your face displayed on billboards. An infraction in one area of life could easily come back to haunt you in another. According to a State Council policy document: ‘If trust is broken in one place, restrictions are imposed everywhere.’

Dr Rogier Creemers, perhaps the West’s leading expert on the system, explains how moral authority has been a central part of Chinese politics for the past two millennia. ‘China never had a separate church in the way that western countries did, and so the moral authority of the church is also held by the state. This isn’t just about people obeying the law; it’s about the state claiming the moral authority to define what virtue is, and then demanding that people live virtuously.’

There isn’t yet a single system of control. The Chinese government is still working on knitting together the various databases and systems so that different parts of government can access data held in different silos. But there are around 40 local trials currently in operation, each of which has different rules and punishments. Once in place, the social credit system will act as a way of enforcing existing laws and regulations.

In China’s tech hub Shenzhen, a city of 12.5 million people, jaywalkers are punished using the social credit system. Pedestrians who don’t cross the road at the right time or do so in the wrong place have their photos posted on a government website, and on billboards on the sides of the roads. One firm, Intellifusion, is reported to be building a system that will automate this with facial recognition technology. Not only will the system be able to identify offenders automatically, it will then text them to let them know they face punishment.

Another local trial is taking place in the city of Jinan, but this one is for dog owners. Individuals start with 12 points, but can lose them for infractions like walking their pet without a leash, or letting the animal bark too much. Lose all your points and the government takes your pooch away.

The private sector has been just as keen to adopt social credit. Sesame Credit was launched by e-commerce giant Alibaba in 2015. Much like Amazon, Alibaba is a platform that connects buyers and sellers. But unlike in America and Europe, most Chinese people didn’t have a bank account until recently, so financial tools such as credit checks were unavailable. A system was needed to create trust within the marketplace.

Enter social credit. Users who opt in to the system are given a score — somewhere between 350 and 950, based on different metrics: how much a user spends, how much personal information has been entered into the app, whether bills and credit card payments have been made on time and how many verified friends a user has.

These metrics are then used as a proxy for trust. If someone has bought plenty of items without a problem, or has friends who use the platform whom the company has already verified, and so on, the system will divine that the person is more trustworthy.

As with the government systems, scores are important. If you have a sufficiently high score, you unlock perks, such as the ability to rent bicycles without paying a deposit, use massage chairs (which are strangely ubiquitous in China) for free, or even fast-track your application for a Schengen visa.

What makes Sesame Credit controversial is that the algorithm that drives it is kept secret. Most users will have no idea how their score is calculated. But the company has admitted it is partially based on the types of products people buy. ‘Someone who plays video games for ten hours a day, for example, would be considered an idle person,’ Li Yingyun, Sesame’s technology director, has said. Buying products for your child would mark you out as a more responsible citizen.

Economies are built on trust and China’s economy has matured at an astonishing rate. Those who support the system say that it’s designed to manage low-level misdemeanors and will help create more trust.

But it’s easy to see where the next steps could lead. You don’t need to read too much dystopian science fiction to imagine how such an opaque system, where a mysterious number decides your rights and privileges, could be used to control a population. Some trials have already led to alarming results. In one region, the phone system was configured so that anyone calling someone on a debtor blacklist was warned that they were contacting an untrustworthy individual.

While we might trust the people currently in charge of the new high-tech security apparatus, how can we be sure that the people in charge in the future will use it responsibly? In other words, even if you inexplicably trust the Chinese government to behave responsibly today, how can you be so sure that Xi Jinping or his successors will behave the same way tomorrow? China’s innovative use of new technology may not just enable perfect surveillance. It will align an individual’s motives with those of the state itself.

Technology is only going to develop further. Processing power will increase, as will facial recognition. The number of devices containing cameras and microchips will increase too. It will keep getting easier to sift through huge amounts of information, in the hunt for anything subversive.

What China has achieved in such a short time is staggering. But the announcement I heard on the bullet train made me nervous. It was an ominous reminder that there is a darker side to China’s growth, which may soon affect us all.

This is one of the most astonishing things I've ever seen (only mild hyperbole). This is the view from the train between two stops on the metro in outer-Shanghai.

If you've ever wondered how China has room for 1.3bn people… this is how. pic.twitter.com/DV6S0ojFRF

— James O'Malley (@Psythor) October 29, 2018

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.