One of the first places Professor Stephen Toope visited as vice-chancellor of Cambridge University was the Chinese embassy in London. He posed for photographs with ambassador Liu Xiaoming and the two men discussed furthering the ‘golden era’ of China-UK relations. Shortly after that 2017 meeting, Toope told Xinhua, China’s state news agency: ‘There will be more opportunities to engage actively with China, a country with an extraordinarily growing influence which a university like Cambridge must pay attention to.’

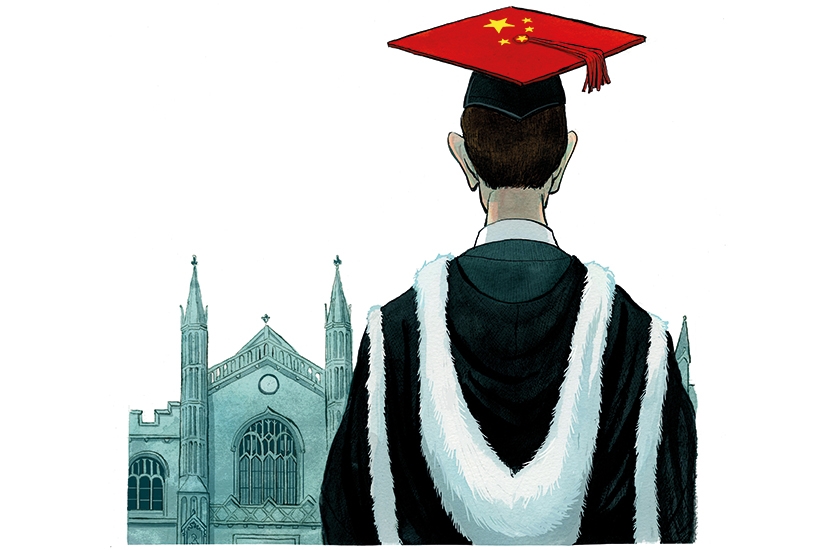

Fast forward three and a half years and the shine has come off the ‘golden era’. But word has been slow to reach Cambridge, where Professor Toope continues his headlong pursuit of Chinese money. China is adept at directing funding towards areas of research which it sees as strategically important and it has targeted a range of British institutions. Few have allowed themselves to be so comprehensively compromised as Cambridge.

The university has begun work on a new home for the Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership. It is retrofitting the city’s old telephone exchange at 1 Regent Street, turning it into the ultimate low-energy building at a cost of £12.8 million ($17.6 million). The building is called Entopia (a play on ‘energy’ and ‘utopia’), a name coined by Lei Zhang, a Chinese billionaire, whose opaque Shanghai-based renewable energy company, Envision, is providing just under half the funds.

When Mr Zhang is not building wind turbines, he is a member of the National People’s Congress, China’s rubber-stamp parliament, and the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, a party advisory body. In March, while Toope was welcoming ‘the most sustainable premises in the University of Cambridge estate’, the NPC was endorsing a law to neuter Hong Kong’s electoral system, snuffing the last signs of life out of democracy in the former British colony.

A month earlier, it was reported that Cambridge’s Department of Engineering had received a ‘generous gift’ from the Chinese company Tencent to help fund research into futuristic quantum computers. In a statement, the department said: ‘Founded in 1998, Tencent uses technology to enrich the lives of internet users.’ A little due diligence would have revealed that Tencent is closely linked to the Chinese Communist party. Its ubiquitous WeChat app (Weixin in China) is a key component of the surveillance state.

In December, Toope addressed by video-link the Beijing Forum, an event organized by Peking University to discuss ‘The Harmony of Civilizations and Prosperity for All’.He said that in a troubled world, collaboration was more necessary than ever. He cited the ‘particularly fruitful’ example of a ‘smart cities’ joint research project in Nanjing, where Cambridge has accepted millions of pounds from the Chinese government to set up its first major research center of this scale outside the UK and the only one bearing the university’s name. The Cambridge University-Nanjing Center of Technology and Innovation will ‘enable the development of “smart” cities in which technology enables sustainable lifestyles, improves health care, limits pollution and makes more efficient use of energy’, Toope told the Forum. ‘Smart cities’ (or ‘safe cities’ as China calls them) bristling with sensors might well improve urban living in different ways, but in the context of China they are primarily instruments of surveillance and repression.

The groundbreaking ceremony for the Nanjing innovation center took place in September 2019. Cambridge University’s website carries a photograph that would not be out of place on the front page of the People’s Daily — drab officials, identical red shovels in hand, awkwardly turning the soil. Toope stands in the middle in a light gray suit. He is beside Zhang Jinghua, Nanjing’s Communist party boss. The website describes the project as Cambridge’s ‘first overseas enterprise at this scale’ which ‘will allow Cambridge-based academics to engage with specific, long-term projects in Nanjing’.

Cambridge’s Board of Scrutiny, a governance body charged with ‘ensuring transparency and accountability in all aspects of university operations’, examined the deal, and concluded that it is a fine example of the sort of relationships the university should be building now that Britain has left the European Union. For all Toope’s principled words about the academic value of collaboration, the deal appeared to come down to money.

‘Developing such activities outside the EU is part of our response to Brexit and the board notes recent announcements of initiatives such as the strategic partnership with the Nanjing municipal government. China in particular is committed to substantial investment in research, which should be a priority for Cambridge given our existing strengths and international profile,’ according to a report of the board’s proceedings. It did hint at possible reputational dangers, noting that as overseas activities were scaled up, so was exposure to financial and what it called ‘other’ risks, which would need to be managed.

A separate report from the university’s ‘general board on the establishment of certain professorships’ accepted the academic case for a Nanjing professorship of technology and innovation in the Department of Engineering, which would be financed from the China deal — from the Chinese government, in other words. It valued the deal at £10 million ($13.8 million). The new ‘Nanjing professor’ is Daping Chu. His college, Selwyn, describes him as ‘one of the leading figures in academic partnerships with China’. The college’s Facebook page carries a photo of Chu in Tiananmen Square, a guest at the Communist party’s 2019 celebrations of the 70th anniversary of its rule.

In September last year the Nanjing government hosted a conference aimed at ‘deepening partnership’ with Cambridge. Zhang Jinghua, the local Communist party chief, gave the welcoming address, thanking Cambridge for its support. ‘Despite COVID-19 and the ever-changing international economic landscape, the trend of innovation cannot be reversed, and the pace of cooperation cannot be stopped,’ Zhang declared. If Toope, attending online, felt in the least bit uncomfortable with that defiant tone, he didn’t show it, responding that he hoped ‘both sides would strengthen cooperation, promote collaborative innovation and jointly cope with major global challenges’.

Cambridge has strongly denied that accepting Chinese money in any way impinges on academic freedom, but events at Jesus College suggest otherwise. Two of the college’s China-focused centers have been criticized for kowtowing to Beijing, and have recently been given the sort of makeover that the CCP’s history-manipulating propagandists would be proud of.

Jesus College set up a China Centre in 2017, and the following year established a UK-China Global Issues Dialogue Centre. The centers initially embarked on programs of China-friendly events that largely steered clear of topics such as Xinjiang, Hong Kong, Taiwan and human rights in general. Their websites borrowed language from Communist party handouts, dripping with jargon about China’s ‘extraordinary transformation’ and its ‘rejuvenation’. The Dialogue Centre was set up with money from the Chinese government’s National Development and Reform Commission, a planning agency recently instrumental in Beijing’s economic vendetta against Australia after Canberra called for an independent inquiry into the origins of COVID-19.

The Dialogue Centre hosted a ‘digital economy governance dialogue’ — a pet subject of Xi Jinping’s, and one which is essentially a euphemism for draconian censorship and digital social control. A subsequent white paper, with a foreword by Toope, declared: ‘A key feature of our discussion was the much more prominent role now taken by China, and Chinese companies, in global communications, and the need for new approaches that fully include them.’ The event was funded by a grant from Huawei. Two of the 36 listed participants were from the company.

The director of the China Centre is Professor Peter Nolan. He was also the first Chong Hua Professor in Chinese Development, a chair sponsored by the China-based Chong Hua Foundation. The professorship was set up in 2012 with a £3.7 million ($5.1 million) endowment and Cambridge claimed at the time that Chong Hua was a private foundation with no links to the Chinese government. It was later revealed that the charity was run by Wen Ruchun, the daughter of former prime minister Wen Jiabao. Ruchun is a former student of Professor Nolan, who also co-authored a book with her husband.

As recently as November, Nolan cautioned students against discussing China’s human rights abuses in Xinjiang and Hong Kong, saying it might not be ‘helpful in advancing mutual understanding’. ‘We have a lot of mainland students,’ he warned.

The websites of both the China Centre and Dialogue Centre now carry more neutral language. The China Centre has sought to salvage its reputation with a more varied program of events. In March, the Dialogue Centre dropped ‘China’ from its title. The spring edition of Jesuan News, a college publication, which announced the name change, carries an extraordinary full-page statement under the title ‘Speaking of China’. It insists: ‘We ensure that academic freedoms are protected by robust governance structures, and it is the College Council’s stated position that no subject is out of bounds.’

The tone of the article is prickly and defensive, asserting: ‘With respect to the growing mistrust and lack of understanding from all sides between China and the West, the College has a role to play to encourage open and honest scholarly enquiry.’ It is an astonishing statement and implies a moral equivalence between President Xi’s growing tyranny and western democratic values, values which British universities were once supposed to embody.

Those values were foremost in the minds of students from Hong Kong when they demanded that Wolfson College strip Hong Kong chief executive Carrie Lam of her honorary fellowship in the light of the crackdown against the pro-democracy movement. Wolfson initially refused. Only after a draconian security law was imposed last year did a statement say that the college was ‘considering’ Lam’s position. Lam eventually took the decision out of Wolfson’s wavering hands, cutting her ties with the college.

Hong Kong students who protested in Cambridge ran into difficulties. One Wolfson student from Hong Kong, Ulysses Chow, said he no longer felt safe after being bombarded with online abuse and even a death threat to his mother.

Perhaps Toope really does believe that by collaborating with Communist party entities Cambridge can make the world a better place. Still, it’s hard not to conclude that the relationship between Cambridge and China has been characterized by astonishing greed and naivety.

Cambridge is often seen to be the pinnacle of Britain’s liberal education system. But it has also shown itself to be truly world-beating when it comes to accepting Chinese money with few questions asked.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.