Hwæt. In British and American universities, fewer and fewer students are studying English, history and other humanities. That’s a job killer for the faculty. It’s time for quick answers — and the English faculty at Leicester University has come up with a beauty. The problem with their curriculum, they have decided, is that it is just not left-wing and anti-Western enough. They must figure students want to study English mostly to learn more about imperialism, capitalism and social theory, not to read and interpret great novels and poetry or to read modern works against the background of a great tradition.

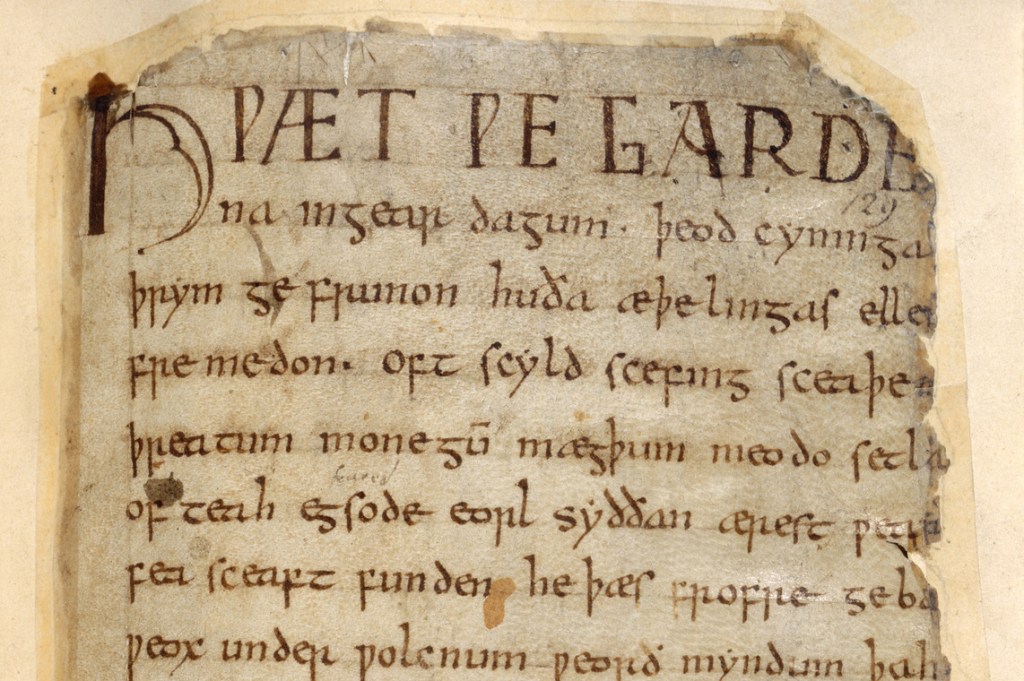

So, out with the old, in with the new. In this case, ‘the new’ reflects the tendentious political preoccupations of the faculty and their most agitated students. At Yale, which has had one of the greatest English departments in the world for decades, the students demanded removal of Shakespeare’s portrait. It’s gone. No problem. Yale’s art history department killed off its iconic course on architectural history because they deemed it too Western. Oh, the horror. No matter that it was the department’s most popular course by far. Leicester’s English faculty decided to drop its traditional requirement for Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales and the medieval epic ‘Beowulf’. All gone, sent to the rice paddies to learn from the glorious peasants.

What’s wrong here? And what’s right? There’s nothing wrong with including some social theory in the humanities. But this theoretical work should meet two criteria. It should be first-rate, not inferior, ideological claptrap, as so much of it is. Second, it should supplement essential works in the curriculum, not supplant them. The goal is to build upon students’ prior knowledge of foundational works in their field. That means English students should read Shakespeare, Jonson, Spenser and Marlowe before they read social critiques of Elizabethan England. They should read Dickens and his contemporaries before they read Marx and Mill. Why? Because the overriding goal for English students should be to enrich their study of literary texts. These primary and secondary categories would reverse for students of sociology. They might be asked to read imaginative literature to enrich their understanding of social structure.

This confusion over what to teach and how to teach it echoes the controversy about pulling down statues and renaming schools. Each of them puts today’s progressive politics ahead of all other considerations and imposes intolerant, modern standards on yesterday’s achievements. In the past week, for instance, San Francisco’s school board ignored the critical problem of reopening its schools so it could focus on renaming them. They know what really matters. Among their decisions: removing Abraham Lincoln’s name. That’s right. The Great Emancipator didn’t rise to the high ethical standards of today’s San Francisco politicians. It should be obvious that, across the country, the names of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson and James Madison are being removed from schools and parks. How long before Washington and Lee University is simply named ‘And’?

Some changes are entirely justified. Indeed, they should have been undertaken long ago. In Memphis, Tennessee, the city council finally removed Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest’s name and statue from a downtown park. That execrable man founded the Ku Klux Klan, which terrorized newly-freed blacks from asserting their full rights. That repressive movement laid the foundations for Jim Crow laws, which suppressed blacks across the American South from the 1890s until the mid-1960s.

This bitter history needs to be taught, not honored. It needs to be explained in the context of contemporaneous political struggles. When that history is morally complex, as so much is, then its light and shadows should be painted in chiaroscuro, not stark black and white.

Our goal should be to understand our past, not erase it or rewrite it with sneering contempt, using anachronistic standards. That’s why it’s a terrible idea for humanities majors, like English at Leicester University, to push aside their commitment to teaching ‘the best that has been thought and said,’ in Matthew Arnold’s words, and replace them with today’s fleeting trends. One sad indicator of these trends that almost no professors today would endorse Arnold’s goal for their curriculum.

They should. The finest works should be the foundation of any serious study of English literature. Eliminating or derogating those works is a catastrophic educational failure.

Second, this focus on great works should not lead to an ossified curriculum or one divorced from today’s concerns. It should include once-marginalized voices and subjects. Students should have ample opportunities to take literature courses focusing on race, gender, class and colonialism. But those courses should feature the finest examples of fiction, poetry and literary criticism. The works should merit inclusion as serious artistic achievements.

Third, courses that deal with politically-fraught subjects should never indoctrinate students and never displace the fundamental goal: helping students gain a broad, deep, critical understanding of the best literature. Teachers should never grade for ideological conformity to their own views. Far too many do — and students know it.

It is shameful that Leicester’s English majors should no longer be required to study Chaucer and other classics. Why? Because Chaucer, Shakespeare, Austen, Dickens, Donne, George Eliot, Milton, Orwell, Woolf, Keats and Wordsworth are not only great writers, their works are in conversation with each other and with their readers, then and now. These works are landmarks and their successors are deeply engaged with them. Sophisticated modern readers should know that — and English departments should aim to form such readers.

Fortunately, some scholars are pushing back against this deforming of the curriculum. Professor Isobel Armstrong, a distinguished scholar at the University of London who earned her doctorate in English from Leicester, returned the department’s honorary degree. Catherine Clarke, an MA examiner in English Studies at the university, resigned in protest. More should join their voices.

Professor Armstrong’s statement, circulated by the University and College Union, eloquently captures the cultural struggle. What Armstrong was protesting was ‘the egregious attack on the integrity of English at Leicester and the attempt to eradicate 1,000+ years of language and literature from the curriculum.’

Exactly.

Charles Lipson is the Peter B. Ritzma Professor of Political Science Emeritus at the University of Chicago, where he chaired both the undergraduate and graduate programs.