Americans may never before have felt their country was farther from its finest hour. And yet, on the Fourth of July last year, residents gathered in the heart of its birthplace for an ever-rarer expression of patriotic sentiment. It was to be a brief display. Blood spilled before the clock struck ten. Though no one saw a gunman or heard gunfire, two police officers were struck by stray bullets on the famous steps of the Philadelphia Art Museum. Word spread quickly, and suddenly no one could be sure whether they were hearing fireworks or gunshots. On the Benjamin Franklin Parkway, patriotism turned to terror, then shrieks gave way to silence.

And then Philadelphia mayor Jim Kenney — unbreakable beacon of fortitude that he is — took to television to reassure his reeling constituency:

There’s not a day where I don’t lay on my back at night, looking at the ceiling, and worry about stuff. I don’t enjoy the Fourth of July. I didn’t enjoy the [2016] Democratic National Convention. I didn’t enjoy the NFL Draft. I’m waiting for something bad to happen all the time. So I’ll be happy when I’m not here, when I’m not mayor, and I can enjoy some stuff.

The feeling he expressed is many things — self-centered, tone-deaf, pathetic — but most of all it’s mutual. Philadelphia, too, will be happy when Kenney is not mayor. Even before this July 4 gaffe, the Democrat Kenney had only a 55 percent approval rating among the city’s Democrats. That percentage could only have gone down when several city council members and a state representative, all of whom are now running to replace him, joined in calling for Kenney’s resignation after the episode. But while he may be awash in relief the second he leaves office, it’s no guarantee we will be. Whether we can “enjoy some stuff” come 2024 is entirely dependent on who rises to replace our miserable mope after the voters pick a successor later this year.

Jim Kenney has done his successor no favors; he’ll be leaving Philadelphia immeasurably worse off than he found it. There’s no shortage of metrics that speak to the dismal performance of his administration. In 2016, the year Kenney took office, the city recorded 277 murders. By his fifth year, we were flirting with our all-time record — 500 in 1990. In 2021, that record was shattered, as Philadelphia saw an unconscionable 562 homicides. In 2022, the count dropped to 516 — a slight decline from a historic high, but still eighty-three more than were recorded in New York City, which has a population more than five times greater than Philadelphia’s. Meanwhile, Kenney’s police department is riddled with corruption and incompetence, and he’s failed to get top-cop Danielle Outlaw and District Attorney Larry Krasner — both of whom, notably, have even lower approval ratings than Kenney — on the same page for enforcement strategy.

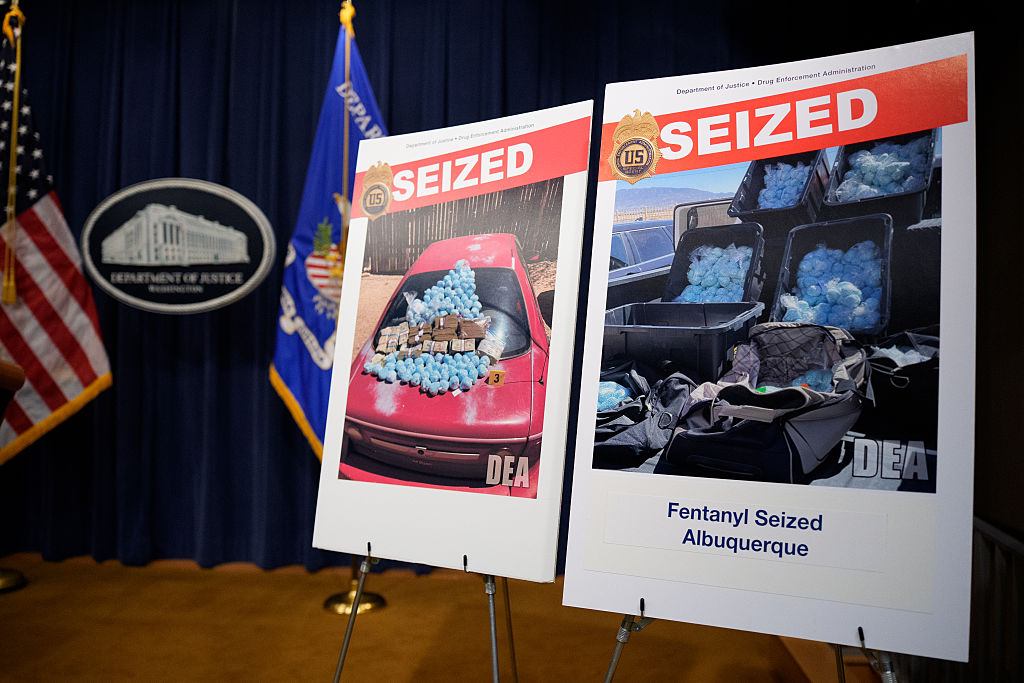

While gun violence is top of mind for Philadelphians looking ahead to the 2023 mayor’s race — roughly 70 percent say it’s the most important problem we face — it is by no means the only basic quality of life issue that’s been festering on Kenney’s watch. Carjackings are also at historic highs. With neighborhoods being ravaged by fentanyl and the veterinary tranquilizer xylazine, overdoses are surging citywide — especially in Kensington, which has long been home to the largest open-air drug market on the East Coast. Rampant addiction, compounded by the highest poverty rate among America’s ten largest cities, has given rise to a serious homelessness problem. Illegal dumping is out of control, emergency response times are lagging, streetlight outages are widespread, the city’s 311 reporting system is a disaster, and one in seven municipal positions are unfilled — roughly 4,000 vacancies citywide.

Philadelphians are hungry for a change of pace from Kenney’s administration. He made promise after promise that he failed to keep on issues ranging from gun violence to waste management to the opioid epidemic. True enough, Kenney was dealt a poor hand with Covid-19, but three years after the virus ground society to a halt, his constituents are tired of hearing “pandemic austerity” as an excuse. Local civic leaders are eager for his successor to clean house, calling for the immediate replacement of top municipal officials.

The question is whether any of Philadelphia’s mayoral candidates are up to the task of reinvigorating the floundering government Kenney will leave behind. It’s a crowded race, so the numbers are on our side — surely one of the ten candidates is the real deal? It’s early yet, and mayoral hopefuls are just now starting to differentiate themselves on policy specifics. But, at the risk of sounding optimistic, one needn’t look far to find signs of shifting tides.

Former councilwoman Helen Gym, for example, is considered by many to be the most progressive candidate in the field. Thus far, on gun violence, she’s promised to “declare a state of emergency and focus all city departments on the common goal of community safety.” She is focused on “increasing the clearance rate” for homicides and shootings, asserting that “we have to bring perpetrators to justice.” She also promised to redeploy foot patrols and put officers “back in our neighborhoods,” using a strong police presence to “reclaim McPherson Square” — a public space in Kensington also known as “Needle Park,” as it’s held captive by the neighborhood’s open-air drug market.

Amid this relatively tough talk on crime, Gym throws in, almost as an afterthought: “I also want to be clear that under my watch we will not roll back the clock on civil rights.” She later came out explicitly against defunding the police, saying we can both be tough on crime and make needed investments in communities, like improved mental health services. Just two and a half years ago, such talk from a progressive politician in a major American city would have been unthinkable. Whereas having a functional criminal justice system once took a backseat to concerns about police brutality, now it seems the opposite is true.

Perhaps that’s because of polling data like the set collected by the Philadelphia Inquirer in April 2022: “Black and Hispanic respondents were more likely to say the city doesn’t have enough police, while white people were twice as likely as black people to say the city has too many. And those more likely to say that the city had enough or too many police officers were either younger, had annual income above $100,000, or have a college degree.” If being a progressive means representing, first and foremost, the interests of your city’s most marginalized residents, then being a progressive in Philadelphia today means exactly what Gym says it means — putting officers back in our neighborhoods.

Now, some might have trouble squaring this contemporary strain of progressivism with Philadelphia’s landslide reelection of its notoriously soft-on-crime, tough-on-cops District Attorney Larry Krasner. But Philadelphians don’t see this as a contradiction. As Inquirer editorial writer Daniel Pearson put it: “People should spend more time thinking about the fact that the median black voter in Philadelphia both wants more police in their neighborhood and supported Krasner. This position is unpopular on Twitter but obviously exists in the real world.” Here, at least, voters are eager for a stronger police presence and higher clearance rates for serious crimes, but not for harsh sentences or free passes for police misconduct.

If Gym is the burgeoning mayoral contest’s most progressive candidate, then her fellow former councilwoman Cherelle Parker is fast emerging as its least — at least when it comes to criminal justice. She told the Inquirer in September that “if you are coming to Philadelphia to buy drugs or commit a crime, we will find you, we will arrest you, we will take your car and we will make it as painful as possible to participate in the illegal economy.” She promised to redeploy “much more” than 300 officers on foot and bike patrol in every neighborhood of the city, and she’s the only candidate who’s endorsed constitutional stop-and-frisk policing as part of an effective crime fighting strategy.

Two other candidates, the moderate real estate mogul Allan Domb and the pragmatic progressive, former city controller Rebecca Rhynhart, have given deeper insight to their public safety policy plans. Domb put out a ten-point plan in January, promising to triple funding for the recruitment of police officers; to seal abandoned buildings and clean vacant lots; and to aggressively crack down on repeat offenders, retail theft, illegal guns and illegal vehicles (like ATVs and dirt bikes). Rhynhart, meanwhile, has offered the most detailed plan for cleaning up the open-air drug market in Kensington. In January, she announced that her administration would “use the Drug Market Intervention strategy to identify street-level dealers, arrest those committing violent acts and give non-violent dealers a warning that continuing to sell illegal drugs will not be tolerated.” She got some blowback for being soft on so-called nonviolent dealers, but the policy has a solid grounding in empirical data, and in any case, just about any clearly articulated and well-organized strategy would be an improvement over the status quo.

Then again, all four of these candidates — Gym, Parker, Rhynhart and Domb — were asked in mid-January whether they would retain current police commissioner Danielle Outlaw, whose tenure has been a disaster. Domb and Gym both said yes; Parker and Rhynhart refused to answer. It’s an open question, then, whether their lofty policy goals will be snuffed out by the power politics of the city’s machine.

For now, all we can safely say is that the end of Kenney’s final term next January can’t come soon enough to satisfy Philadelphians. And that political winds in the city seem to be shifting away from tolerance of civic dysfunction. Philadelphia is ready once again for a strong leader who can put an end to the violence, the lawlessness, the corruption and above all the staggering municipal incompetence they see all around them. Time will tell if Kenney’s successor fits the bill.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s March 2023 World edition.