Straight after the British government’s epic defeat in the House of Commons on Tuesday night, the Chancellor, Philip Hammond, the Business Secretary, Greg Clark, and the Brexit Secretary, Steve Barclay, held a conference call with business leaders to try to reassure them. The principal worry was about ‘no deal’. The Chancellor’s message of comfort was revealing of where power has shifted to. He emphasized how backbenchers are maneuvering to stop no deal. In other words, they needn’t take his word that it wasn’t going to happen; they should take parliament’s. It was an admission that the government is no longer in control of Brexit.

Further evidence of this power shift came from Clark, who said the scale of the defeat and the need to reach out to parliament meant that the UK would now end up negotiating a deal that was closer to the EU. Unsurprisingly, given his historic opposition to Brexit, Clark sounded quite upbeat about this prospect. Indeed, those in the cabinet who have always wanted a softer Brexit see an opportunity in this defeat. They think that ideas they argued unsuccessfully for in cabinet, such as a customs union, are now back on the table.

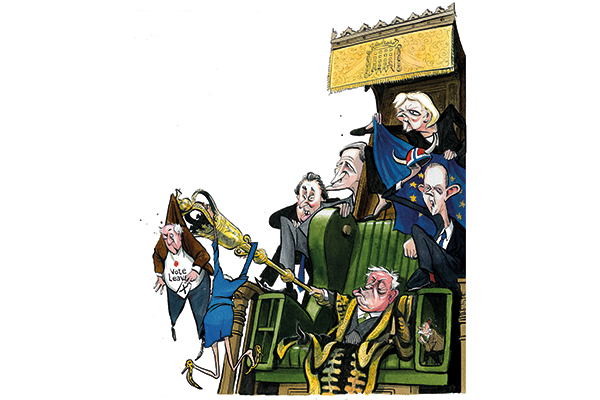

These ministers who want a softer Brexit have also been helped by the missteps of their main internal foes, the Tory MPs of the European Research Group. Their shambolic attempt to unseat Theresa May before Christmas has won her a year’s grace from any challenge to her leadership of the party. This has put her in a unique constitutional position: she’s a Prime Minister who can be removed by parliament, but not by her party.

As a result, May knows that the greatest threat to her survival is not watering down Brexit — parliament would be happy with that — but if she is seen to be embracing no deal. This prospect could force enough Tory rebels to vote with Labour for her to lose a confidence vote. Her survival instinct — perhaps her defining feature as a politician — means she’ll be careful not to risk this. In any case, she’s temperamentally averse to leaving without a deal.

So May needs a deal that can get through the Commons — and the brutal truth is that this is likely to lead her to a softer Brexit. The EU won’t, as one secretary of state points out, give the UK what the ERG wants, but it might give us the softer Brexit some Labour MPs desire. As this secretary of state, who has avoided joining any of the Brexit camps in the cabinet, puts it, ‘The only way to get there is to have them in and ask them what they want.’

Some in May’s circle think that the Labour leadership’s support can be obtained for a price. Jeremy Corbyn, they reckon, doesn’t want a second referendum. Nor does he want to get any of the blame for a no-deal Brexit. This makes them think that Labour will back a new deal with the EU if it extracts some very visible (and embarrassing) concessions from the government.

But as always with Brexit, things aren’t quite as simple as this. There aren’t enough Labour rebels to help May: she needs 117 MPs to change their mind. She therefore needs Corbyn’s help, and it’s unclear why he would offer it. ‘The beauty of his position is that, whatever is agreed, he can say “I’d have done it differently,”’ laments one cabinet minister. ‘As soon as he helps deliver it, he is saying “This deal is good enough for me.”’ This minister complains that those who think a softer is the way out of this impasse ‘can’t count’, as there simply aren’t enough Labour MPs who are prepared to break with Corbyn and who want a softer Brexit rather than a second referendum.

Even if a huge number of Labour MPs were prepared to break with their leader and back a May-negotiated deal, they would then need to rebel time and time again, sticking with the government for the weeks of votes needed to get a Brexit deal into law. If this were not difficult enough, at least some Labour MPs would need to be prepared to support the government in a no-confidence vote. If May did decide to ally with Labour MPs, there would be plenty of Tories willing to vote her down before the deal went through.

At this point, it is tempting to conclude that parliament won’t agree on anything and Britain will default to no deal. But even those in the cabinet who privately would quite like this to happen don’t think it will.

First of all, May doesn’t want no deal. One of the main reasons Tory Brexit hardliners tried to remove her before Christmas was that they thought she’d never move to what they regard as a world-trade Brexit. They were right in that analysis. ‘She’ll desperately try to avoid doing that,’ reports one of the cabinet ministers who knows her best.

Those who oppose no deal are also working to find a way to allow the Commons to block it if the government does try to go down that path (as Nikki da Costa discusses here). At first blush, these schemes look too clever by half. But John Bercow’s keenness to secure his place in the history books — or as he would put it, ensure parliament has a say — means that a Commons block on no deal will likely be constructed by hook or by crook before 29 March. It is also worth remembering that many Tories who backed Remain and then voted for May’s deal think that in doing so they have discharged their responsibility to the referendum result. They now feel more at liberty to contemplate steps that they wouldn’t have before, such as the revoking of Article 50.

By the evening of March 29, one of three seemingly impossible things must happen. Either a deal needs to be approved, or the government needs to go ahead with no deal, or Article 50 needs to be extended or revoked.

The EU would extend Article 50 in certain circumstances: to give parliament more time to pass its deal or to plan a new referendum with Remain on the ballot paper, or even to hold a general election. What is more doubtful is whether the EU would extend Article 50 just to allow the British parliament and executive to keep debating what this country wants.

Right now, the least unlikely option is a deal of some kind. The threat of Brexit being stopped could help May whittle the Tory rebellion down. If she can win over what one minister calls the ‘moderate hardliners’, the number of Labour MPs she would also need to convince would become more realistic.

The biggest single reason for the size of May’s defeat on Tuesday night was that so many MPs — whether they wanted no deal or no Brexit — thought that voting against her deal would make it more likely that they would eventually get what they want. They can’t all be right. As it becomes clearer who was mistaken, the chances of a deal getting through increases.

Theresa May is not a politician who trusts people easily. One of the hallmarks of her premiership has been the tightness of her inner circle and how few politicians are admitted to it. But she now finds her political future dependent on persuading MPs across the House to trust her. A leader who has sought to make a virtue of her intransigence must now display more agility than any Prime Minister in living memory.

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.