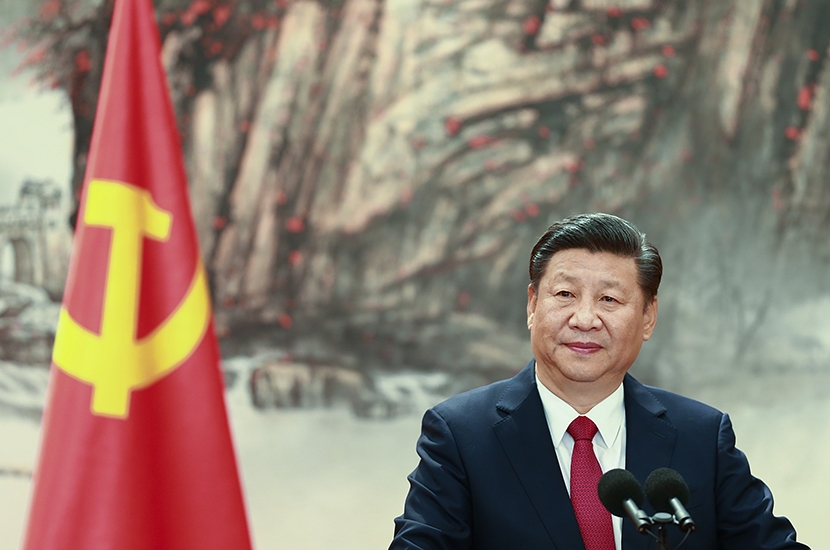

Chinese leaders love to use the phrase ‘win-win’, but they actually hope to win twice and leave other nations in positions of relative disadvantage. The Chinese Communist party’s behavior during the COVID-19 crisis is a case in point.

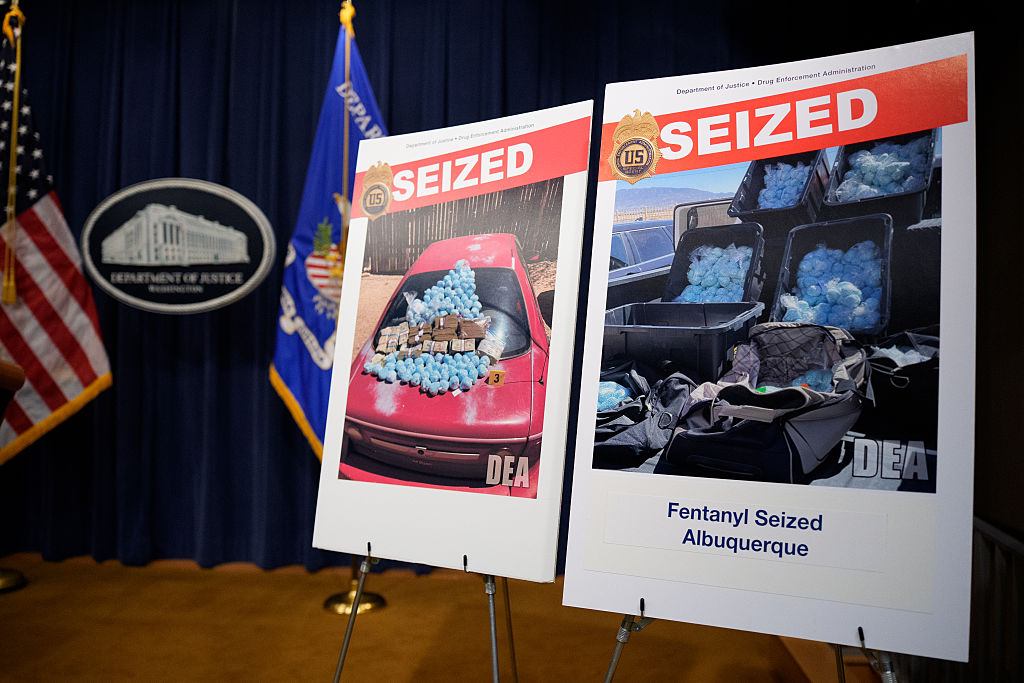

In the midst of the global pandemic, the People’s Liberation Army and the Ministry of State Security have conducted cyber-attacks against hospitals, pharmaceutical companies and medical research facilities developing COVID-19 therapies and vaccines. Triumphing in the race for a vaccine would help China emerge from the crisis in a position of relative advantage economically and psychologically, while reinforcing the idea that China’s authoritarian mercantilist system is superior to democratic free market systems. Win-win.

After its cover-up of the initial COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan, the CCP then engaged in heavy-handed ‘wolf-warrior diplomacy’ — so called after the Wolf Warrior Chinese propaganda action films. China’s diplomats and agents have used disinformation not only to obscure its responsibility for the pandemic, but also to portray European and American responses to the crisis as indicative of the ineptitude, corruption and incompetence of their democracies.

When Australian leaders had the temerity to suggest an investigation into the origins of the pandemic, the editor of CCP-backed newspaper the Global Times, Hu Xijin, described Australia as ‘a bit like chewing gum stuck on the sole of China’s shoes’ and suggested that it was time to ‘find a stone to rub it off’. This month, after the UK criticized China for extinguishing freedom in Hong Kong, Chairman Xi’s ambassador in London, Liu Xiaoming, threatened ‘consequences’ for Britain. He chided: ‘If you dance to the tune of other countries, how can you call yourself Great Britain?’ But if the UK and other countries dance to China’s tune and succumb to intimidation, the world will be less free, less prosperous and less safe.

The UK is more than capable of acting on its own initiative and of leading others by its example. Policy Exchange has initiated a commission on the Indo-Pacific, with representatives from Japan, India, South Korea, Indonesia and Singapore. The idea is to establish Britain’s role as a key player in a reinvigorated multilateral order that resists Chinese aggression and pursues a positive, democratic and free market vision for the region.

Britain’s close relationships with India, Japan, South Korea and Australia can help unite the region against the CCP’s coercive power through the promotion of democratic governance as well as fair and reciprocal economic relationships across the Indo-Pacific.

As Britain’s diplomats and development experts manage the merger of the Foreign Office and Department for International Development, they might look to prioritize such efforts to strengthen democratic institutions and contrast them with the closed authoritarian system that China promotes. What CCP leaders see as weaknesses — freedom of expression, of assembly and of the press; freedom of religion and freedom from persecution based on religion, race, gender or sexual orientation; rule of law and the protections it affords life and liberty; and the belief that government serves the people rather than the other way around — are in fact strong bulwarks against Chinese aggression. British diplomats might also lead efforts to prevent the CCP’s subversion of international organizations such as the World Health Organization and the World Trade Organization.

But the threats to a free and open Indo-Pacific are graver than wolf warrior diplomacy, predatory economic practices and cyber-attacks. In recent months, the People’s Liberation Army has used the COVID-19 pandemic as cover for aggression from the South China Sea, where its navy and maritime militias stepped up attacks to advance their specious territorial claims; to the East China Sea, where the PLA navy increased incursions into Japanese territorial waters near the Senkaku Islands; to its Himalayan border with India, where the PLA has violated the Line of Actual Control multiple times and last month bludgeoned 20 Indian soldiers to death.

Taiwan, though, has received special attention. The PLA conducted night-time drills in the Taiwan Strait and its fighter and bomber aircraft carried out threatening overflights. The PLA chief of the Joint Staff Department, Li Zuocheng, vowed to ‘resolutely smash any separatist plots or actions’. The PLA has grown in power thanks to sustained rises in Chinese defense spending (an increase of more than 800 percent since 1992) and the integration of advanced weapon systems (hypersonic missiles, an aircraft carrier, fourth generation fighter jets and submarines). If its commanders continue to amplify the chauvinistic rhetoric coming from the other Chinese leaders, they may precipitate a crisis through their aggressive actions.

[special_offer]

The UK can play a critical role in fostering deterrence and convincing Chinese leaders that military aggression is unlikely to succeed. The UK’s role in Nato, as well as the Five Power Defense Arrangements with Singapore, Malaysia, Australia and New Zealand, and the Defense Logistics Treaty with Japan, can be used to strengthen collective security through exercises that demonstrate the military capabilities necessary to defeat any attempt to seize territory or deny freedom of navigation and overflight in the region. The forward positioning of military capabilities such as the British aircraft carrier HMS Queen Elizabeth would signal a strong commitment to preserving peace through strength.

Perhaps most important, the UK is well positioned to convince Chairman Xi and Chinese Communist party leaders that their efforts to divide and conquer the nations of the free world are doomed. Britain’s ‘global perspective’, frequently emphasized by Boris Johnson, is vital to cope with a range of Chinese aggression that reaches far beyond the Indo-Pacific region. And while British diplomatic, military and economic policies are vital, it may be the British people, across the private sector and civil society, who have the strongest voice of all.

The CCP takes extraordinary measures to deny its people a say in how they are governed. It may have not quite appreciated how citizens of free and open societies react to their authoritarian model. Initiatives such as Policy Exchange’s Indo-Pacific commission demonstrate that far from dancing to anyone else’s tune, the British are uniquely well-placed to help other countries understand what is at stake.