And just when everything was looking so tidy — the Ukraine war, a new Covid subvariant, mass shootings, a woked-up Disney operation — what should come along to light up our lives but 8.5 percent inflation? And who, I ask you, ought to wonder?

Like acid reflux and obstreperous two-year-olds, inflation ranks high among human durable goods: always looming, never gone for long, even when it pulls back, and even then leaving its indelible marks. This, due to another human durable: the determination of governments, autocratic as well as democratic, to mishandle the pretended spreading of economic joy.

Inflation of the kind now circling the world is a government affair, its consequences often worsened by governments’ attempts to make it go away while, at the same time, blaming those awful capitalists. Those of us advanced enough in years to remember stick-shift Chevys and Fibber McGee’s Closet have not the least trouble stitching together the extensive pattern of government gaffes that consistently drive up prices and multiply consumer anxieties.

World War II provides the background. Its probably unavoidable system of government-enforced wage and price controls caused wages and prices, once decontrolled, to seek their marketplace levels in terms of supply and demand. A period of price stability ensued, during which pay-phone calls and soft drinks cost a nickel, a dress shirt 5 bucks, and gasoline 21 cents a gallon.

Along came Lyndon Johnson, as the Vietnam war and the Great Society jointly ensued, to promise America it was strong enough to have guns and butter at the very same time. To put flesh on the promise, Washington provided unbalanced budgets and tons of new money, a gift of the Federal Reserve. It worked — if the objective was to send all this money chasing a supply of goods that hadn’t materially increased. This, predictably, produced bidding wars that drove up prices.

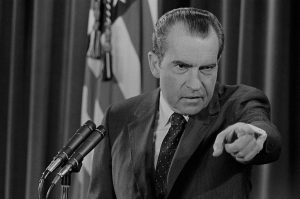

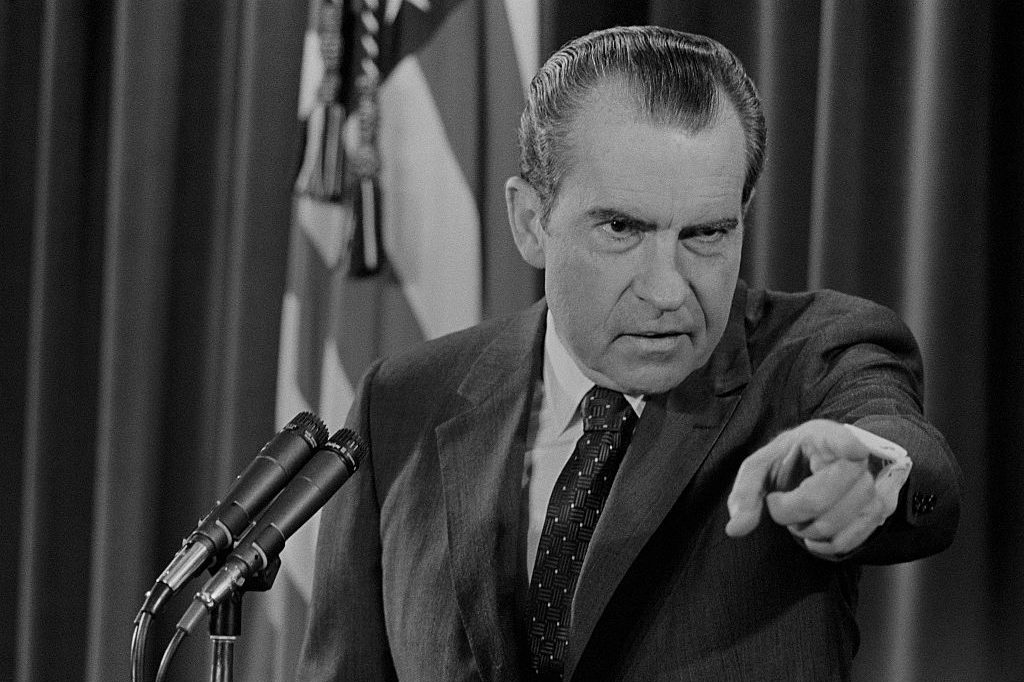

Richard Nixon found the spending temptation hardly less resistible than Johnson had. Was he going to cut spending? Of course not. He brought back wage and price controls, in a form less stringent than during the war but no better suited to the challenge of letting the marketplace find its own sensible level, based on supply and demand. Exit Nixon, enter Gerald Ford, whose Madison Avenue “Whip Inflation Now” (W.I.N.) campaign had about as much to do with whipping inflation now as a keg of bourbon would have had to do with turning out the Baptist vote.

C’mon, fellas. Didn’t anybody have a better idea? Jimmy Carter, during the so-called Energy Crisis, had the very, very, very bad idea of whipping gasoline inflation by calling for a windfall profits tax on gasoline. He didn’t get it, but he did, against, presumably, some measure of philosophical reluctance, do at least two things right. He presided over the deregulation of the airlines, and he encouraged Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker’s escalation of very low interest rates, which predictably discouraged borrowing and spending and, in the end, closed out the inflation era that had commenced under Johnson.

By then, Ronald Reagan was in the White House. Reagan had a soft side when it came to spending, but he had something none of his predecessors since Calvin Coolidge had had — an engrained respect for the decisions of the marketplace accompanied by disdain for the discredited belief that Government Knows Best, And Does Best. Which it doesn’t, by the way, pious progressive pretensions to the contrary. Reagan benefited from the Volcker campaign against inflation, but he made sure the matter of seemingly insuperable price hikes wouldn’t come up on his watch. He whipped inflation by letting marketplace processes have their way, generally speaking.

Inflation, circa 2022, will sputter out at some point, inasmuch as most of its effects are politically unpopular: so unpopular they are expected to help drag down the Democratic vote this fall. Two major government mistakes are responsible for our present inflation: first, the Democrats’ determination last year to spend, and hence borrow, nearly $2 trillion supposedly on Covid-fighting and relief, and second, the Biden administration’s unstinting hostility toward the industries that supply our energy, hence requiring at the very least modest incentives to produce more, not less, energy. Hence the current average price of $4.10 a gallon (Why, oh, why, didn’t I dig a large hole, when I could have, and buy up all the 21-cent gas then available?)

One irony of inflation is that we ought to have learned after all these centuries that controlling, or, more accurately, trying to control, the marketplace never works. The Roman historian Lactantius made this point in the 4th century A.D. Hundreds of years later, the Weimar Republic, trying to pay war reparations without raising taxes, reduced the value of the mark to 25 billion to the dollar — and wiped out the savings of Germany’s middle class, giving one large boost to a certain Herr Hitler.

The more it changes, said the French journalist Alphonse Karr, the more it’s the same damn thing: le meme chose. Must have something to do with the human capacity for drawing dark blinds over human reason and rationality.