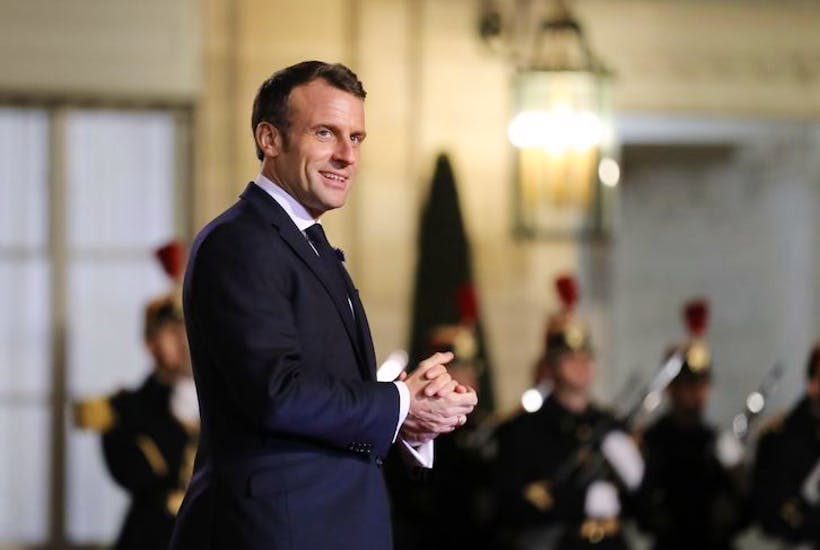

Boris Johnson and Emmanuel Macron have more in common than just a desire to ‘get Brexit done’. The pair also recognize the threat posed to the West by Islamic extremism – and the British prime minister can learn from the growing determination of the French president to stand strong against the hardliners and in defense of mainstream Islam.

Last weekend in Paris an estimated 13,500 people gathered for a ‘Stop Islamophobia’ march, among them Jean-Luc Mélenchon, leader of the left-wing France Insoumise party, Esther Benbassa of the Green party and Philippe Martinez, head of the CGT union. According to those present at the march, Muslims are uniquely oppressed in France, although government statistics from the Ministry of Interior suggest acts of aggression against Muslims are at their lowest level since records began in 2010. Meanwhile, attacks on Christians and Jews are rising, with anti-Semitism rocketing 74 percent in the last decade.

To express their outrage, one of the event’s organizers, Marwan Muhammad, led the crowd in a cry of ‘Allahu Akbar.’ As he explained later, Muslims ‘have had enough of the media misrepresenting this religion expression for a declaration of war.’ According to this week’s edition of Le Canard enchaîné, the president reportedly told aides that ‘to fight racism is always necessary but to protest next to Salafists and patent anti-Semites is the conga of opportunists.’ In his opinion those on the left who attended the march have ‘turned their back on its history and its values…to win three votes at the municipals [elections in March 2020], they have sold their soul.’

His language is important. He takes aim at Salafism, a new strain of political Islam whose adherents often use the word ‘Islamophobic’ to deter or attack their enemies – even Muslim ones. The Muslim human rights activist Sara Khan has said how she has been ‘accused of being an Islamophobe because I have delivered projects supported by the UK authorities to dissuade young Muslims from joining Isis.’ Macron sides with her, and the majority in France who believe the word ‘Islamophobia’ is an Islamist strategy that aims to undermine and ultimately erode the Republic’s Laïcité (secularism).

France, like all countries, suffers from anti-Muslim hatred. Last month, a former candidate for Marine Le Pen’s National Rally party allegedly shot and seriously wounded two Muslims outside a mosque in the city of Bayonne. More often the bigotry is subtle, such as employers rejecting résumés from applicants with North African surnames, and as a consequence Macron’s government takes this seriously, and has announced they are stepping up the random testing of companies to eradicate discrimination.

But at the same time, he is standing up to the hardliners. And in this, he has French public support. A 2018 report from the country’s Commission on Human Rights reported that 81 percent of French people thought Muslims should be free to practice their religion in ‘good conditions’; what they didn’t like was the creeping conservatism of the religion with 59 percent declaring opposition to the burkini and 86 percent against the burka.

Like most mainstream politicians in France – and the UK – Macron is reluctant to use the word ‘Islamophobia,’ knowing that it can be used as a tool by hardliners to stop scrutiny of their agenda. Manuel Valls, the former Socialist prime minister, was the first prominent MP to challenge the term. He cut his political teeth in Évry, a district south of Paris, where Islamic extremism has strong roots. After being told by liberal Muslims within the community that Islamists were using ‘Islamophobia’ as a method of discrediting anyone who questioned their hardline ideology, Valls refused to use the term from 2013 onwards, describing it as the ‘Salafists’ Trojan Horse’. His position made him many enemies on the left and cost him the chance to stand in the 2017 presidential campaign as the Socialist candidate. That honor went to Benoît Hamon, who was present at Sunday’s march, and who only polled a humiliating six percent in the first round of the election.

The same is likely to be true for Jeremy Corbyn next month, and Boris Johnson should make more of the Labour leader’s dubious connections to Islamist groups. That will doubtless lead to accusations of ‘Islamophobia’ but the prime minister should dismiss them as Macron did last month when he gave an interview to Valeurs Actuelles, a conservative weekly magazine regarded by many on the left as beyond the pale because of its belief in faith, flag and family. During a walkabout at Honfleur, Macron was accosted by a young woman who said it was ‘repugnant’ to give Valeurs Actuelles the time of day. ‘One should talk to everybody,’ replied the president, a novel concept to the liberal intelligentsia of the 21st century.

Johnson was accused of Islamophobia last year when, while defending a woman’s right to wear the burka, he likened niqab-wearers to letter boxes and bank robbers. The PM is more liberal in this regard than Macron, who recently reiterated his opposition to the headscarf in schools. His education minister, Jean-Michel Blanquer, went further, saying the garment ‘is not desirable in our society’. Does that damn them as Islamophobes or are they the defenders of Republican values against an ideology that is intolerant and intransigent?

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.