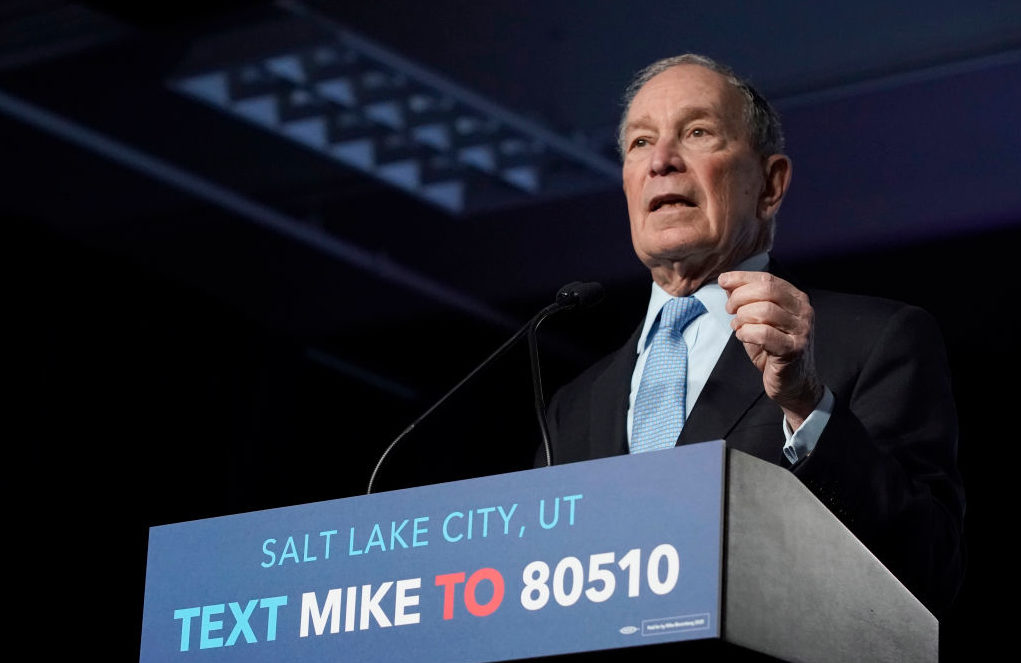

Mayor Mike Bloomberg didn’t fare so well in his debut appearance in Wednesday night’s Democratic debate in Las Vegas. Every other candidate was intent on exposing various sordid parts of his history, including his mistreatment of women and his former comments on banning the redlining that caused the 2008 financial crisis. But I was surprised that other parts of his record didn’t receive any attention—particularly his comments on K-12 education. After all, Bloomberg once said that if he had things his way, he’d ‘cut the number of teachers in half’, ‘double [their] compensation’ and ‘weed out all the bad ones and just have good teachers’.

To his credit, it does seem that Bloomberg is the only remaining Democratic presidential candidate with an eye on reforming the K-12 public school system. He opened a record number of charter schools while mayor of New York City and intends to continue that trend from the White House. His competitors have almost solely focused on increasing funding, but Bloomberg bucks that trend by leaning into disruptive ideas for improving school and teacher quality. For proponents of education reform and school choice, that’s good news, right?

Well, not so fast.

While Bloomberg is open to improvements like the expansion of charter schools, he’s really got an overly technocratic mindset. His laser-focus on test scores and holding ‘failing’ schools accountable is troubling, because that’s the approach that’s dominated the country’s thinking about public education over the last few decades. But this thinking has been thoroughly picked apart over the last 20 years, and for good reason. It hasn’t delivered on many of its promises and has caused a lot of new problems.

Long has Bloomberg defended the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) policies that got their start under George W. Bush. For those who don’t know, that’s when federal policymakers began imposing tougher standards on states for defining proficiency on reading and math, and required thorough testing regimens. The goal was to make all students learn more by having higher consequences for low performance, and it did have some positive effects. But, overall, its rationale is now widely recognized as flawed. Among other problems, these standards led to the proliferation of state school report cards, a metric that ranks schools based on test scores but often fails to tell the whole story.

Expansion of federal accountability over this period also prevented school leaders from making decisions that were right for their individual schools, tying the hands of those closest to the students. NCLB expanded high-stakes testing in a way that forced teachers to narrow their curriculum to subjects covered by the tests. To this day, many states are afraid to let local leaders try different approaches to curriculum or budgeting. They’re too afraid of bad performance metrics — which could cause funding cuts, among other unfair consequences.

The former mayor is right in that teacher quality is one of the single most important factors in determining the success of a young student. But it’s difficult to define what the measure of a good teacher ought to be, so lawmakers shouldn’t be so confident in enforcing their standardized policy metrics. Some teachers can get students to make better grades, but that doesn’t always translate to better life outcomes later on, such as higher job earnings. Other teachers who do best at getting their students to be more engaged in class may be doing them a better service in the long-run than more test prep-focused teachers. So who should decide which ones should be ‘weeded out’?

Well, not Bloomberg. And he’d agree if he looked at the data he claims to support in K-12 reforms. There are ample reasons to be more humble about education policy.

Does raising salaries or implementing performance evaluations improve teacher quality? That depends on where you look. Has an increased emphasis on testing been good for students? Well, the evidence is mixed at best. Top-down accountability under NCLB and later Obama-era initiatives have been accompanied by stagnant student achievement. Even in looking at how school districts spend their money, results vary. As Georgetown’s Dr Marguerite Roza points out, ‘two high-poverty districts can spend the same amount of money — even in the same way — and still get different results.’

Thankfully, the data is bound to improve, and we’ll learn more about how to make education better. In the meantime, lawmakers, including Mayor Bloomberg, should shy away from hardlining. Only one thing is sure: everything works somewhere, but nothing works everywhere. As it turns out, the best argument for more school choice isn’t that we know what reforms always work, but, rather, that we don’t.

Yes, Bloomberg gets it right on some K-12 issues. But that’s only to the extent that he allows educators the room to try new things — not to enforce what he thinks is right.