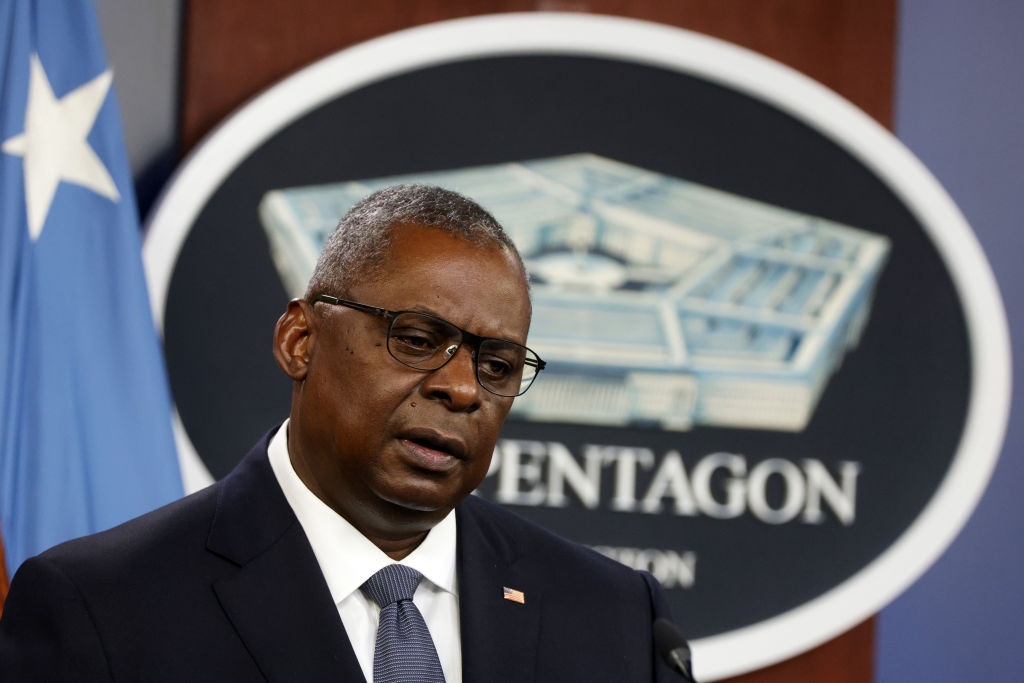

Nearly ten months after President Biden ordered defense secretary Lloyd Austin to undertake a comprehensive, across-the-board review of America’s military overseas, the Pentagon finally concluded the study this week. And it landed with a loud thud of disappointment.

So far as we can tell (the entire product won’t be released to the public), the results of the Global Posture Review (GPR) range from unimaginative to pitiful. Or, in the words of one congressional aide familiar with the findings, “No decisions, no changes, no sense of urgency, no creative thinking. Lots of word salad.”

Of course, the GPR is hardly the first government report to be classified this way. The Pentagon in particular operates on bureaucratese; you can’t get through the first page without hitting an acronym. But ultimately, the posture review isn’t about grammar or syntax — it’s about choices. And from what we know, hardly any major choices were made.

For those who strongly believe that the military is overstretched, performing too many tasks, and guided by an ingrained assumption that American primacy in a multipolar world is still appropriate, this was a disappointment.

Ideally, the GPR would be an exhaustive, honest exercise in which predispositions were challenged, uncomfortable questions were asked, and tertiary priorities were sacrificed at the altar. Instead there is no change to the bottom-line US position, which seems to treat all regions of the world as equal in terms of importance.

Rather than draw down American forces in areas that are of marginal strategic importance (like the Middle East), the review sticks with the same posture it has maintained for two decades. What Pentagon officials classify as a US shift away from the Middle East is in reality a series of small-ball tactical changes, like the redeployment of air defense systems based in Saudi Arabia, that are no longer needed. The tens of thousands of forces stationed in the Middle East won’t be leaving anytime soon, despite the fact that Washington is supposedly seeking to wind down the decades-long counterinsurgency wars of the past.

According to the GPR, the US force posture won’t be changing in Europe either. Keep in mind that Europe has been whole, free, and at peace for decades and is more than capable of defending itself militarily, even if the vast majority of European states are still nowhere close to meeting NATO’s 2 percent of GDP defense spending benchmark.

If Western Europe were at risk of being swallowed up by the Russian army, the United States would have good cause to maintain its current presence of around 60,000 troops. But notwithstanding Moscow’s military modernization and saber-rattling over Ukraine, the prospects of Vladimir Putin ordering some kind of conventional invasion of Europe is about as likely as yours truly winning the Powerball jackpot. Russia is a problem, and one the Europeans are trying to manage through a combination of dialogue and deterrence. Yet a heavy US military presence in Europe disincentivizes European governments from taking ownership of their own neighborhood. After all, why do the lifting when you can outsource the work to Uncle Sam?

If there is one region that will see an uptick in US military activity over the next two to three years, it’s the Indo-Pacific. The Biden administration’s foreign policy is largely centered on what it terms “responsible competition” with China. A key aspect of this approach relies on sustaining working relationships with senior Chinese officials, including the occasional summit between President Biden and China’s Xi Jinping.

The military invariably gets drawn into the policy as well, with freedom of navigation operations in disputed waters regularized and joint military drills with allies and partners becoming more frequent. The GPR calls for the US to improve airfields on the island of Guam, deploy additional bombers and fighters to Australia, and make permanent an attack helicopter squadron in South Korea.

None of these enhancements, though, are cost free. Greater deployments in the Indo-Pacific bring more risk for US forces, who will be exposed to China’s impressive array of long-range cruise and ballistic missiles. It’s also highly likely that Beijing would respond in some fashion to a more beefed up American presence in Asia. Did the officials involved in the posture review take any of this into consideration?

Washington tends to view defense strategy through the prism of money. If only the military had more resources, the argument goes, then we could attain perfect safety and security. Questions are rarely asked about whether the US really needs to send troops to NATO’s eastern flank, whether warships need to sustain the current pace of naval operations in the Strait of Hormuz, or whether nearly 1,000 ground forces truly need to be in Syria. Instead, those policies are taken for granted as righteous and necessary. It’s one reason the defense budget has grown to an astounding $780 billion.

Yet more funds won’t fix what is wrong with American foreign policy. What does have a chance of fixing it, however, is policymakers having the gumption to make hard choices. Prioritizing everything means prioritizing nothing. Regrettably, the Global Posture Review takes the path of least resistance.